Georgians put learning English ahead of Russian

- Published

Lisa Maiorello believes that learning English will prove useful to Georgian children

Lisa Maiorello, a teacher from Washington DC, is injecting a little American flavour into her lesson.

She stands at the front of a classroom, handing out laminated photos of cars to fifteen-year-old boys, whose eyes light up.

There is a Cadillac for Giorgi, an Aston Martin for Tornike and Nika gets a Chevrolet.

"It costs $50,000," declares Lisa, picking on Giorgi, in the front row. "Is it too expensive for you?"

The cars might only be picture versions of the real thing, but the exercise is enough to stimulate the conversation.

"It's a little bit expensive," says Giorgi, confidently, turning to wink at his friends. Girls burst into giggles in the back row.

Volunteers

For most of the pupils, Lisa is the first foreign teacher they have ever had. She is one of 1,000 volunteers who have been invited by the Georgian government.

They have come not only from the US, but also from Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand as well as Scandinavia and eastern Europe.

Lisa has been posted to school number 34, a functional building nestled in the concrete jungle of Georgia's second city, Kutaisi.

She's in no doubt that her arrival will be useful to her students.

"They learned Russian. Now they have something to add to that. It will broaden their world," she said.

The drab, grey school walls are a product of the Soviet era, when all children studied Russian and Georgian: an age young Georgians want to forget as their pro-Western government continues to pull the country out of Russia's orbit, almost seven years after it won power in a revolution.

Compulsory

Education minister Dimitri Shashkini has decided to make English lessons compulsory from September 2011. He says it is already the most popular foreign language among secondary school pupils.

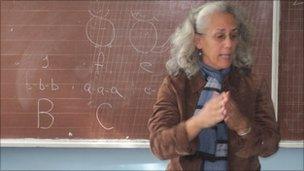

Manana Patiridze argues that Georgia's children must not forget Russian

"In a country like Georgia which doesn't have natural gas, which doesn't have oil, our main resource [is] human. That's why education is so important for us and is so strategic for Georgia."

But Mr Shashkini's scheme is not without its critics.

Manana Patiridze, a Russian tutor, is sorry to see the language of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky and Pushkin on the wane.

"We have very important cultural links with Russia. Russian is the language of Georgia's neighbours," she says.

"Georgia's children still need Russian in order to travel within the region. We mustn't forget Russian."

The pupils in Kutaisi seem intent on learning English rather than Russian. A quick show of hands reveals it is the subject of choice for more than half of Lisa's class. None of them lists Russian among their favourite subjects.

"I like learning English because I want to go abroad to study there. I know that then it will be easier to find a job after that," says Thea, a 16-year-old student.

Could the sour political relations between Russia and Georgia, at an all-time low since their conflict in 2008, be driving the attitude of Georgia's youngsters?

"You know there was a war between us and Russia and you know Russian is not a very popular language," says another member of Lisa's class.

Poorer backgrounds

The modernisation of Georgian schools began more than five years ago, when corruption was rife in the post-Soviet education system.

Simon Janashia believes Georgia's education system penalises poorer students

By 2008, according to Unesco, Georgia was still spending less of its state budget on education than any other former Soviet country.

According to the same figures, only 25% of youngsters were continuing their studies at university.

The education minister says he is starting to address these issues. He says £2.8m ($4.5m, 3.3m euros) has been spent on text books for children from poorer backgrounds.

"Education brings prosperity," says Mr Shashkini. "When the children have this feeling of fairness [and] when there is no corruption in the exam system, [there will be] results."

But Simon Janashia, assistant professor at Tbilisi's Ilia State University, says the system is still not entirely fair because it penalises poorer students who cannot afford extra tuition.

"To pass higher entrance exams to university it is almost required for you to get a private tutor because you are competing with the other students for the high stakes tests. Because of this the socially disadvantaged have less chance to get into the popular universities and faculties," he says.

It may be that it takes time to achieve the fairness Mr Shashkini talks about.

Meanwhile, back in Kutaisi's school number 34, Lisa wraps up her lesson.

Her class of 15-year-olds does not have to think about going to university just yet. For now, all the talk of fast cars and cash - in English - is enough to carry them through the day.

But it will be a lot longer before a majority of children in their age group get the chance to fulfil their dreams and study abroad.