Why Russians backed anti-police rage

- Published

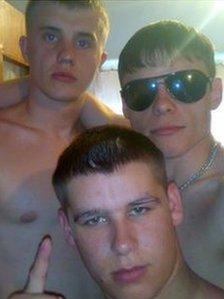

Andrei Sukhorada (top) and Aleksandr Sladkikh (bottom) are now dead, and Maxim Kirillov (middle) is in prison

Six young Russians became so angry about police brutality in their area that they took up arms to fight back. Lucy Ash asks what motivated the group and why so many ordinary Russians supported their extreme actions.

Vladimir Savchenko takes me into his son Roman's bedroom to show me his school photographs and collection of toys neatly arranged on a shelf.

"He won lots of prizes in athletics," says Mr Savchenko, fingering a clutch of medals hanging on the wall.

"But he liked kick-boxing best."

The 17-year-old is now behind bars awaiting trial. He is the youngest of the six men who declared war against law enforcement officials this year. The group, which called itself the "Primorsky Partisans", became notorious across Russia.

In a video, made while they were hiding in the forest, the young men wear army fatigues and hold guns. Stripped to the waist, Alexander Kovtun, the group's leader, directly addresses the police:

"This is not some spontaneous act," he says. "No. We planned it and did it on purpose, to kill you gangsters, because you are the real criminals. You provide cover for drug-trafficking, prostitution and the theft of wood from our forests."

The young men come from the remote village of Kirovsky in Russia's Primorye, or Maritime, region near the Chinese border. It is seven time zones east of Moscow.

I went there to meet their families and to try to discover why the youths took the law into their own hands.

Police brutality

The Savchenko family live in a decrepit block of flats with rusting balconies and rubbish-choked stairways. Over coffee, Roman's father, a truck driver, complains about the large bribes he has to pay to stop officers from confiscating his driving licence.

Nine years ago, his elder son Valentin died in a police station after getting involved in a street fight.

Then, earlier this year, Roman was arrested and accused of stealing a lawn-mower. Mr Savchenko denies his son was involved but claims the police tried to beat him into confessing the crime.

"They roughed him up so badly that he joined the group of other young guys seeking revenge on the police."

One of them was Roman's school friend Andrei Sukhorada. From the age of 13, the police would arrest the boys every time there was trouble in the village, according to Andrei's sister Natasha.

Natasha Sukhorada blames police torture for her brother Andrei's decision to take up arms

"They would charge them with all sorts of crimes," she says. "They tortured them by putting black plastic bags over their heads and blowing cigarette smoke into them."

The breaking point came in 2008 when a fight broke out at a disco. Natasha says Andrei was hurt and taken to hospital but when he came out he was abducted by local police, driven into the forest and beaten.

She says he was stripped of his clothes and left to die in sub-zero temperatures 10km (six miles) from the village. Andrei survived, but the family claims its complaint to the prosecutor was ignored.

In a building made of white breeze-blocks, I meet the acting head of the police station, Major Vasily Skiba. He denies all the allegations made by the families of the group about beatings by his officers and says all complaints from the public get investigated.

Then he switches on his computer, asks for my USB memory stick and transfers some video clips. They seem to show the young men driving round the town throwing snowballs and shouting abuse. They also yell "Allahu Akbar!" - Arabic for "God is great!"

'Dirty acts'

But if Andrei and his friends really were nationalistic skinheads, as some suggest, why were they saluting Islamist fighters? Could it be a sign that they were angry enough about police abuse to side with anyone who opposes the Russian state?

The group struck for the first time in February in the regional capital, Vladivostok, when the members killed a traffic policeman.

Vladimir Savchenko is proud of his son's sporting achievements

Three months later, they stabbed another policeman to death, and attacked police cars, injuring more officers.

The authorities launched a manhunt with tanks and helicopters. They tracked the groups down to a flat on the Chinese border.

Andrei Sukhorada and his friend Aleksandr Sladkikh died in a shootout with police. The remaining two were captured and are facing life in prison.

In the prosecutor's office in Vladivostok, spokeswoman Avrora Rimskaya condemns the group.

"We cannot justify the acts of people which go against society," she says. "No matter how loud their slogans are. They say loud words but commit dirty acts."

Public support

But to the authorities' disgust, many ordinary Russians back the "Primorsky Partisans". Graffiti across the city reads "Glory to the Partisans" and "Partisans your courage will not be forgotten".

On the seafront, a young sailor tells me the police deserved the treatment they got and added that it "was a brave thing for six guys to do".

Avrora Rimskaya says the Partisans' acts cannot be justified

At the car market, another young man is blunter. "They did the right thing - the police are just legalised bandits," he says. In Moscow, 71% of callers to a popular radio station supported the description of the youngsters as "Robin Hoods".

Two-thirds of Russians fear the police, according to the country's leading opinion pollster, the Levada Centre. Brutality is commonplace and corruption endemic.

President Dmitry Medvedev has promised to clean up the force with a police reform bill now going through parliament. Critics say it is more about preventing whistle-blowing than genuine change.

Mikhail Grishankov, chairman of the parliamentary security committee, sighs noisily when asked about the group.

"They are bandits and my opinion is, of course, negative, but you have to ask why it happened," he says.

Even this former KGB officer who is loyal to the Kremlin admits that the public distrusts the people who are supposed to protect them.

"The support they got shows society has lost trust in the police."

You can listen to Lucy Ash's full report inCrossing Continentson BBC Radio 4 at 1100 GMT on Thursday 25 November and 2030 GMT on Monday 29 November. You can also listen via theBBC iPlayeror download thepodcast.

- Published17 November 2010