Silvio Berlusconi: Italy's perpetual powerbroker

- Published

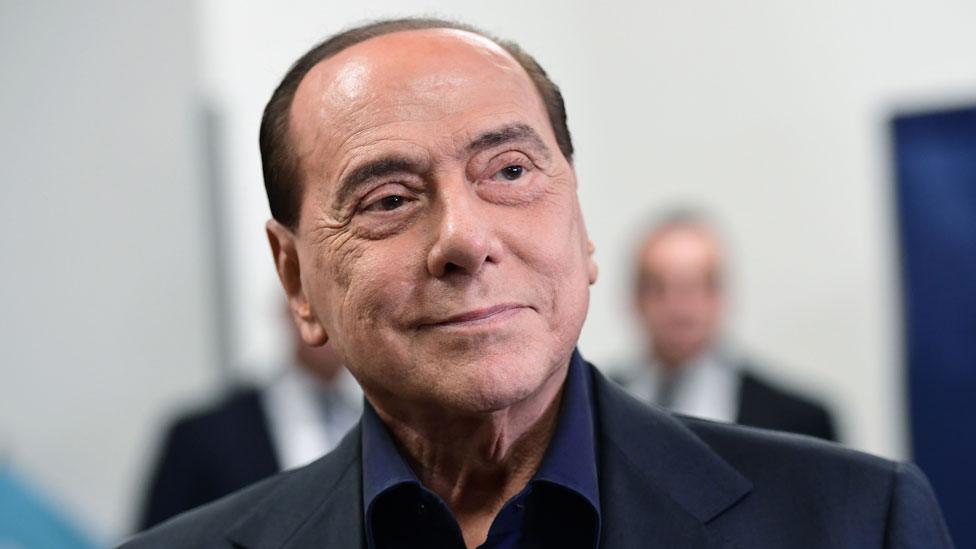

Berlusconi smiles after casting his vote in Milan, May 2019 - an election he would win a seat from

Few Italians have wielded more influence and attracted more notoriety than Silvio Berlusconi: billionaire businessman, four-time prime minister, and member of the European Parliament.

For years he successfully brushed off sex scandals and allegations of corruption, until Italy's eurozone debt crisis in 2011 saw his influence temporarily wane.

Worse was to come for the man whom many Italians had come to see as untouchable.

He was convicted of tax fraud in 2013 and ejected from the Italian Senate. Another conviction in 2015 made it look like his political career was finally over.

But despite suffering a heart attack that his doctor said could have killed him in 2016, and having emergency bowel surgery in 2019, the charismatic showman was set for yet another political comeback.

Even though he was banned from holding public office due to his criminal record, he led his centre-right Forza Italia party to moderate electoral success in 2018. And a year later, with his ban lifted, won himself a seat in the European Parliament at the age of 82.

From crooner to business mogul

Berlusconi, 82, remains one of Italy's richest men. He and his family have built a fortune estimated at $6.4bn (£5bn; €5.7bn) by US business magazine Forbes., external

Born on 29 September 1936, Berlusconi was a child during World War Two. Like many Milan youngsters, he was evacuated and lived with his mother in a village some distance from the city.

He began his career selling vacuum cleaners and built a reputation as a singer, first in nightclubs and then on cruise ships.

Berlusconi's children play a big role in running his business empire: his daughter Barbara was vice-president of AC Milan

He graduated in law in 1961 and then set up Edilnord, a construction company, establishing himself as a residential housing developer around his native Milan.

Ten years later he launched a local cable-television outfit - Telemilano - which would grow into Italy's biggest media empire, Mediaset, controlling the country's three largest private TV stations.

His huge Fininvest holding company now has Mediaset and Italy's largest publishing house Mondadori under its umbrella, and has stakes in daily newspaper Il Giornale among other companies.

Berlusconi sold AC Milan football club to Chinese investors for £628m (€740m) in 2017.

His children - Marina, Barbara, Pier Silvio, Eleonora and Luigi - all take part in the running of his business empire.

The highs and lows of Forza Italia

In 1993, Berlusconi founded his own political party, Forza Italia (Go Italy), named after an Italian football chant.

The following year he became prime minister, heading a coalition with the right-wing National Alliance and Northern League.

Many hoped his business acumen could help revitalise Italy's economy. They longed for a break with the corruption and instability which had marred Italian politics for a decade.

Berlusconi has dominated Italian politics since the 1990s

But rivalries between the three coalition leaders, coupled with Berlusconi's indictment for alleged tax fraud by a Milan court, confounded those hopes and led to the collapse of the government seven months later.

Then came a series of ups and downs:

He lost the 1996 election to the left-wing Romano Prodi but by 2001 he was back in power, in coalition once more with his former partners

Having headed the longest-serving Italian government since World War Two, he was again defeated by Mr Prodi in 2006

He returned to office in 2008 at the helm of a revamped party, renamed the People of Freedom (PDL)

His support drained away in 2011, as the country's borrowing costs rocketed at the height of the eurozone debt crisis, and he resigned after losing his parliamentary majority

In February 2013, he came within 1% of winning a general election - close enough to play a part in the governing coalition

As tensions mounted over his tax fraud conviction, the party split and Berlusconi relaunched it under the old name, Forza Italia.

He was away from the political centre stage for about four years after he was expelled from parliament.

From 2018: Berlusconi's handshake advice for BBC reporter

In 2018, Forza Italia was left out of the coalition with the right-wing Northern League despite a solid election performance – and Berlusconi could not have held public office himself in any event, due to his criminal record.

But that ban was overturned the same year, when he was deemed "rehabilitated" by the courts - and he announced he would contest the May 2019 European elections.

In those elections, Forza Italia picked up less than 10% of the vote in Italy – but enough for several seats, including Berlusconi's.

Milanese courtroom dramas

Much of Berlusconi's political career has been plagued by a litany of legal battles. A native of Milan, he has frequently complained of being victimised by its legal authorities.

In 2009, he estimated that over 20 years he had made 2,500 court appearances in 106 trials, at a legal cost of €200m.

Berlusconi eventually carried out community service as part of his conviction for tax fraud

He denied embezzlement, tax fraud and false accounting, and attempting to bribe a judge. On numerous occasions he was acquitted, had convictions overturned or watched them expire under a statute of limitations.

But he received a setback when in 2011 the Constitutional Court struck down part of a law granting him and other senior ministers temporary immunity.

By the end of the year he was out of power, and in October 2012 he was given four years for tax fraud and barred from public office. Berlusconi declared his innocence and spoke of a "judicial coup".

Because he was over 75, he was handed community service, working four hours a week with elderly dementia patients at a Catholic care home near Milan.

Berlusconi's women and bunga-bunga parties

Berlusconi's struggles in the political arena and the courtroom have been accompanied by a string of lascivious reports about his private life.

He met second wife Veronica Lario after she performed topless in a play.

When he was photographed at the 18th birthday party of aspiring model Noemi Letizia, his wife decided to divorce him.

But his reputation was tarnished most by allegations of raunchy "bunga-bunga" parties at his private villa attended by showgirls. The reports culminated in a conviction of paying for sex with an underage prostitute.

Amid the scandal, both Silvio Berlusconi and Karima El Mahroug denied they had sex

In October 2010, it emerged that Berlusconi had called a police station asking for the release of a 17-year-old girl, Karima "Ruby" El Mahroug.

She was being held for theft and was also said to have attended his "bunga-bunga" parties.

In June 2013 he was found guilty of paying her for sex, and of abuse of power. The case was eventually overturned in 2014.

Read more: An explanation of bunga bunga

But he is now set to stand trial accused of bribing a witness - something he denies.

Berlusconi has always maintained he is "no saint" but firmly rejects claims he has ever paid for sex with a woman, saying: "I never understood where the satisfaction is when you're missing the pleasure of conquest."

Related topics

- Published12 May 2018

- Attribution

- Published28 September 2018

- Published17 November 2017