Russia's most important court trial

- Published

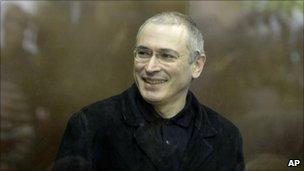

The former oil tycoon was first arrested in 2003 on charges of tax evasion involving his company, Yukos

The most important court trial in modern Russian history is drawing to an end.

It is widely believed that it is not only the fate of the two defendants - former oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his business partner Platon Lebedev - which the judge will now decide at the end of the month.

Many believe that the outcome of the trial will foretell the result of the next presidential election in 2012.

On this theory, an acquittal or even just a lenient sentence will indicate a possibility of incumbent Dmitry Medvedev serving another term.

A harsh verdict meanwhile will imply that his predecessor, current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, is still calling all the shots and is determined to return to the Kremlin.

In his second tenure, liberals hope, Mr Medvedev would try to get out of his powerful mentor's shadow and shake off some of the KGB-associated legacy that to a great extent has shaped the domestic and international policies of Russia in the past decade.

It is thought that Mr Putin's comeback, meanwhile, might entail further tightening of the screws and a prolonged period of enforced "stability" which, in the eyes of his critics, means nothing but all-permeating stagnation and corruption.

'Absurd' charge

Mr Khodorkovsky and his partner are accused of stealing some $25bn (£16bn) worth of oil - or practically all the oil their company Yukos produced between 1998-2000, and all the oil it exported between 2000-03 - and then laundering the proceeds.

The prosecution is calling for a sentence of 14 years.

Independent jurists say they find the charge absurd. But plenty of observers said the same thing about many of the charges at the previous trial in 2005.

Last time Mr Khodorkovsky and Mr Lebedev were found guilty of underpaying billions of dollars in taxes. The figure was so extraordinarily high that on appeal the Moscow city court slashed it six times while bizarrely reducing the length of the prison sentence by one year only - from nine to eight years.

Whatever its legal merit, very few people are prepared to take the new case against Mr Khodorkovsky at face value. Even the worst enemies of the former tycoon are convinced that he is in the dock for something else.

Interestingly, that seems to include Mr Putin himself: in one of his recent interviews the prime minister spoke in support of a lengthy prison sentence for the former billionaire, citing some other alleged crimes that the defendant has never been charged with.

Powerful precedent

Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev: Close friends or arch-rivals?

Mr Khodorkovsky is not popular with ordinary Russians: they can't forgive him for getting immensely rich in the 1990s.

But the selectiveness of Russian justice has registered by now: the public has realised that only those "oligarchs" who dare to stand up to the authorities have problems with the law.

Only 13% of those polled in September by Levada Center said they believed the charges, external, down from 29% in February. (Roughly twice as many, 24%, said they did not believe the charges.)

Mr Khodorkovsky made a lot of enemies among the ruling elite and his fellow businessmen by insisting early this century on adopting Western standards of transparency for his businesses while the rest continued to cloak their affairs in secrecy.

It is rumoured that he made another fatal mistake by refusing to "share" his huge earnings with the powerful bureaucrats who are used to regular backhanders - something meekly accepted by the Russian business community as a necessary evil.

In other words, Mr Khodorkovsky challenged the very foundations of the oligarchic system, the symbiosis of power and wealth that makes Russia what it is now.

And then on top of all that he offered financial support to opposition political parties in order, as he put it, to develop pluralism in the country. And that, probably, was the last straw.

Can Judge Viktor Danilkin go against the grain? It is not easy to break the deeply rooted Stalinist tradition of seeking to satisfy the nation's rulers while disregarding the facts or intricacies of the law.

So it's improbable, but if it happens it may create a powerful precedent and greatly encourage all those who want to see their country change.

"Two years have passed since a new president came to power, and many of my compatriots have regained hope - hope that Russia will become a civilised country with a developed civil society, free of lawlessness, corruption and injustice by officials," Mr Khodorkovsky said in his last word to the court in November.

Of his own fate he was more pessimistic. "I am ready to die in jail," he said.

- Published15 December 2010

- Published2 November 2010