Italian mayor saves his village by welcoming refugees

- Published

Mayor Lucano has turned the asylum seekers' arrival into a win-win situation for all sides

You can hear the children from the other side of the village square. Their excited voices bounce off the medieval stone walls and archways.

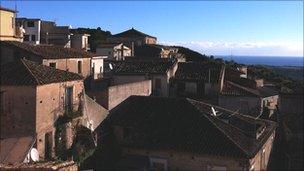

The sound comes from the newly restored Palazzo Pinnaro, a handsome building with views over the rooftops and the Ionian Sea.

Inside the classroom, boys and girls from Somalia, Albania, Iraq and elsewhere are reciting something from the blackboard. It is a poem about friendship. Some falter over the unfamiliar Italian, some are already fluent.

Domenico Lucano stands in the corner watching the class. "Kids are very quick. It only takes them five or six months to become proficient," he says.

"They make me proud and they give me hope that this place has a future. In 2000 our school was shut because we had so few pupils. Now it's flourishing."

Virtuous circle

Yet Mr Lucano, a stocky man with quick brown eyes and a firm handshake, has pulled off an extraordinary trick. He has managed simultaneously to create employment, stop a mass exodus from his village and to find a solution to the controversial issue of asylum seekers.

The local school was able to reopen, and stay open, because of the immigrants' children

Even more striking is that this experiment has worked in Calabria - one of Italy's poorest regions, which recently witnessed race riots. Dozens of demonstrators and police were injured last January in the nearby town of Rosarno after white youths fired air rifles at a group of Africans working as fruit pickers.

But immigrants are actively encouraged to come to Riace, where the mayor has created a special scheme for them.

Today more than 200 refugees from a dozen countries work and live side by side with locals.

Riace is just a few miles from the coast, perched on top of a hill above fields full of sheep and groves of orange trees.

It is a beautiful village of 1,700 people but for decades several houses have lain empty. The occupants left to build new lives elsewhere, in the north of Italy or travelling as far as New Zealand, Argentina and the US.

Mayor Lucano has put the new arrivals into some of these abandoned homes and turned others into craft workshops.

Down a narrow side street we enter a room with lemon-coloured walls where a young woman called Lubaba is making glass ornaments. Separated from her parents during the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, she suffered abuse as a maid in Addis Ababa and eventually escaped to Italy.

Lubaba arrived pregnant in a small boat carrying 250 people. "The journey was awful," she recalls. "We were squashed like sardines and the sea was rough. I was desperately thirsty but there was nothing to drink."

Now she says her life is transformed.

Local jobs

She is grateful to Mr Lucano, whom she calls Mimmo - the nickname by which he is known to everyone in Riace.

Mayor Lucano's scheme has also stopped some local people from leaving.

At the other end of the table, Irena, a local woman with long brown hair, is blowing glass over a flame. She says most of her friends and relatives had to go north to get a job.

But she found part-time employment in the workshop and in the shop where the handicrafts are sold to tourists.

Irena is one of 13 villagers in Riace receiving a salary of 700 euros (£582) a month from the integration programme.

Local woman Irena will now not need to leave Riace to find work

The Italian state provides around 20 euros per day for each refugee, to cover their accommodation, food, medical expenses, training and children's education.

Mayor Lucano argues that in these cash-strapped times, the government is getting a bargain. He calculates that per person per day his scheme is nearly four times cheaper than keeping asylum seekers in a detention centre.

The grandson of a cobbler and son of a local schoolteacher, Domenico Lucano has attracted global attention. Recently he came third in a contest for the world's best mayor. He has given his global village a grand title - la Citta Futura or City of the Future.

It all began one morning 12 years ago when Mr Lucano, himself a teacher, saw some refugees from Kurdistan landing on the beach below his village.

Initially he helped to organise shelter for them. Six years later, when he was elected mayor, he was in a position to do more for the asylum seekers and to save his dying village.

Mafia 'intimidation'

"This was a ghost town before the boat arrived," he says over a plate of steaming pasta in his office. "Psychologically speaking, everyone had already packed their bags, ready to leave."

Riace was facing a gloomy future before the arrival of the asylum seekers

But his project has not met with everyone's approval. After lunch, he stops at a door and shows me two bullet holes in the glass. Mr Lucano believes it is evidence of intimidation by the Calabrian mafia, the notorious 'Ndrangheta.

Mr Lucano says the mob dislike his integration model because they can see that it works and because it challenges their grip on the region.

"We will not be intimidated," he adds. "There is too much at stake."

Europeans on the Edge is on BBC Radio 4 every day from Monday 10 January to Friday 14 January, at 1545 GMT. The edition on Mayor Lucano of Riace will be broadcast on Tuesday 15 January. You can also listen to them on the iPlayer.