Belarus crackdown tests EU influence

- Published

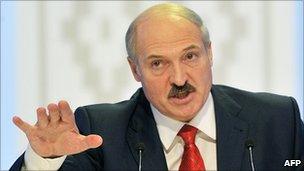

The police crackdown follows the pattern of previous elections won by Mr Lukashenko

European aspirations for a liberalisation in Belarus have been dashed by the bloody confrontation between protesters and police on election day, and the subsequent crackdown on opposition activists.

Tensions between the EU and Belarus are now greater than at any time since the last, controversial presidential election in Belarus in 2006.

In Brussels on Wednesday the EU foreign policy chief, Baroness Ashton, urged Belarusian Foreign Minister Sergei Martynov to release political detainees and stop the harassment of opposition activists.

Belarus opposition leader Alexander Milinkevich has called for a dual approach, focused on isolating President Alexander Lukashenko whilst making it easier for ordinary Belarusians to travel to, study and work in, the EU.

Poland and Lithuania have already dropped visa fees for Belarusian citizens. The other EU member states continue to impose a levy considerably higher than that paid by Russians or Ukrainians - Belarusians pay 60 euros (£50), the others, 35.

In addition to the condemnation of the Belarusian authorities from individual member states, there appears to be a consensus across the EU that sanctions against Belarus must be reimposed and strengthened.

Mounting pressure

EU governments are considering whether to reimpose a travel ban on Mr Lukashenko and his top aides.

The foreign ministers of the Netherlands, the UK, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Poland have all called for clear signals to be sent to Minsk.

Comments from EU diplomats suggest up to 100 names are being studied. Visa sanctions were initially imposed by the EU in 2006, but suspended in 2008 amid signs of a political thaw in Belarus.

The only voice of "dissent" has been Italy, which has usually insisted that dialogue with Minsk is the only way to bring about political change in the country.

The EU could also look at restrictions on the fees paid - especially by Germany - for Belarusian oil products; and freezing Belarusian official assets in the EU.

Soviet legacy

But would any of this matter? Belarus's foreign policy is generally oriented towards Russia, some other ex-Soviet republics and parts of the developing world.

President Lukashenko won overwhelmingly but the opposition disputes the official count

Belarus has aimed primarily to secure markets for its industrial and military goods.

President Lukashenko has been in power since the summer of 1994, but the number of trips he has made to European summits can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

So the EU is faced with the dilemma of not only reimposing practical sanctions, but also rethinking its whole political approach.

Since 1996, when Mr Lukashenko changed his country's constitution to give himself unlimited powers, the EU has alternated between policies of engagement and dialogue, and periods of isolating and condemning the Belarusian leader.

Andrei Sannikov, another opposition leader, says the EU should stop "dreaming of Europeanising Lukashenko".

Given Mr Lukashenko's continuing grip on power, the EU appears to have failed in its ambitions to bring about democratising change in Belarus.

Old alliance

The country participates in many European structures, yet remains impervious to EU criticism or sanctions.

Indeed, a spokesman for the Belarusian Foreign Ministry, Andrei Savinykh, last week blasted the EU for what he called a "counter-productive policy". He accused the EU of not wanting to understand the real political and social situation in Belarus.

In recent years, Belarus has looked towards improving relations with the EU when its relations with Moscow have been troubled. The two countries have built a "union state", abolishing many inter-state restrictions, such as export tariffs and controls on cross-border movements.

So it was a sign of how poor relations had become that one state-owned national television network in Russia last year ran a documentary series alleging that the Belarusian leader was corrupt, connected to political murders, and possibly psychopathic.

Yet, just weeks before the December presidential vote, Belarus and Russia appeared to have agreed upon a reconciliation, at least at a political level.

Many Russian commentators suggest Russia has adopted a policy of "better the devil you know", and is not ready to see its neighbour undergo major regime change.

Ukraine's 2004 "Orange Revolution", when pro-Western politicians successfully ousted the Moscow-backed presidential candidate, had a lasting impact on Russian policy towards its neighbours.

Nonetheless, Belarus is highly vulnerable to Russian economic pressure, especially higher gas and oil prices, or new energy import tariffs.

So far, Russia has insisted that political events inside Belarus since the December election are the "internal affair" of Belarus, whilst condemning the beating and detention of a number of Russian journalists who covered the crackdown.

- Published11 January 2011

- Published31 December 2010

- Published30 December 2010

- Published21 December 2010