Stolen Khodorkovsky film in Berlin Festival premiere

- Published

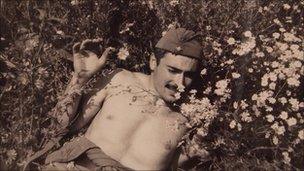

Khodorkovsky progressed from Communist leader to Russia's richest man and then opposition symbol

A documentary about jailed Russian oil tycoon, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, has been premiered at the Berlin Film Festival despite twice being stolen in recent weeks. The BBC's Dina Newman attended the event and spoke to the film's director, Cyril Tuschi.

"I was hoping to make a feature film about Khodorkovsky, but reality surpassed my wildest fantasies, so I realised it would have to be a documentary," says the director, visibly relieved that his five-year project has finally made it on to the screen.

The tape was stolen twice: first in Bali in Indonesia, where Cyril Tuschi was editing the recordings, and then from his office in Berlin, just days before it was due to be submitted to the festival.

Police have no clue as to who could have been behind the burglaries.

'Like a Bond movie'

"It's like a wound. I haven't been to my office since. I hope the police are right and it's nothing more than an ordinary burglary."

The past five years have turned into an emotional rollercoaster for Tuschi, ever since he started filming in eastern Siberia, without any funding, back in 2005.

For three years, he was unable to see the jailed oligarch, had no reply to his letters, and managed to obtain just one photo of him taken by a cellmate on a mobile phone.

Very early on, he noticed he was being watched.

"We got off a train in Chita in Eastern Siberia, at four o'clock in the morning. The platform was empty except for this guy with the mobile phone, and he says very loudly 'there are three people here'."

At the time, he panicked but he soon saw the funny side, deciding it was a regional intelligence official making it clear that he was on his tail.

"It was like a James Bond movie - I turned around and saw a car with dimmed lights following us all the way to the house."

The climax of the film is an on-camera interview with Mikhail Khodorkovsky, thought to be the only footage of its kind since the businessman's arrest in 2003.

After days of turning up at Khodorkovsky's second trial, Tuschi was suddenly allowed to film a 10-minute interview with him in court.

"Five armed guards were standing behind me, and one of them was tapping me on the shoulder, as a countdown. I had no cameraman with me so I had to film it myself. I was so excited that I suddenly forgot all my questions. After years of no reply to my letters, I forgot what to ask!"

Bullet-proof glass

Possibly the film's strongest image is Khodorkovsky's smile seen through bullet-proof glass

One question he did ask is the central question of the film: why did Khodorkovsky decide to go back to Russia and face trial, when he could have escaped abroad?

The jailed tycoon explains that he could not leave his business partner, Platon Lebedev, as a hostage to the authorities. He adds that he believes in the rule of law - and finally smiles, pointing out that everyone makes mistakes.

That smile, seen through bullet-proof glass, is possibly the film's strongest image.

Clearly most Russians will not see Khodorkovsky as a saint - a man who built up the country's second largest oil company and himself became Russia's richest man.

It is hard to imagine how anyone could have gone so far without turning a blind eye to the law.

But Tuschi insists his aim is not to judge Khodorkovsky's guilt or innocence but rather to observe the reversal of fortune in his life.

The former tycoon's letters from prison do not show any remorse, just deep regret that he abandoned his family, and sadness about the ruthless cuts he had to make to turn his business about ten years ago to ensure its survival.

In the course of his life, Khodorkovsky has moved from Communist leader during his youth to enthusiastic capitalist, now becoming a jailed symbol of opposition to Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

"The main lesson of the film is that people can change, no matter how late in life," says Tuschi.

"And this for me is a symbol of hope."

- Published22 December 2013

- Published14 February 2011

- Published31 December 2010