Chirac: A life in French politics

- Published

Jacques Chirac's political career closed with the end of his second term as president in 2007

Jacques Chirac served two terms as French president and took his country into the single European currency.

He moved from anti-European Gaullism to championing a European Union constitution that was then rejected ignominiously by French voters.

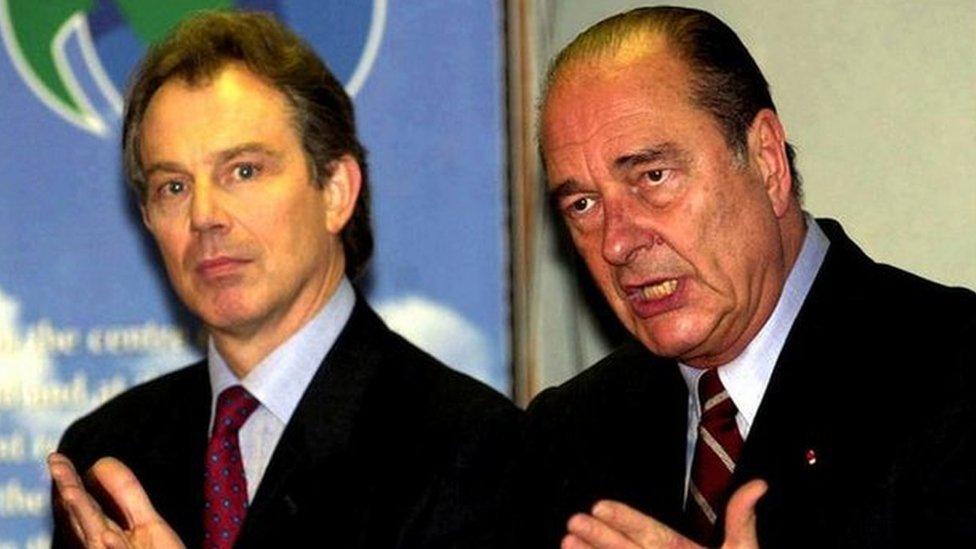

His refusal to back the US-led invasion of Iraq only worsened his already difficult relationship with the UK's then Prime Minister Tony Blair.

And Chirac's reputation at home was tarnished when, after leaving the Élysée Palace, he was convicted of corruption that took place during his long tenure as mayor of Paris.

Jacques René Chirac was born in 1932, the son of a bank manager who later became the managing director of the Dassault aircraft company.

Educated at the elite Ecole Nationale d'Administration, the elite academy for aspiring civil servants, the young Chirac flirted with communism and pacifism.

He served for a time in the French army reserve and was wounded during the French colonial war in Algeria.

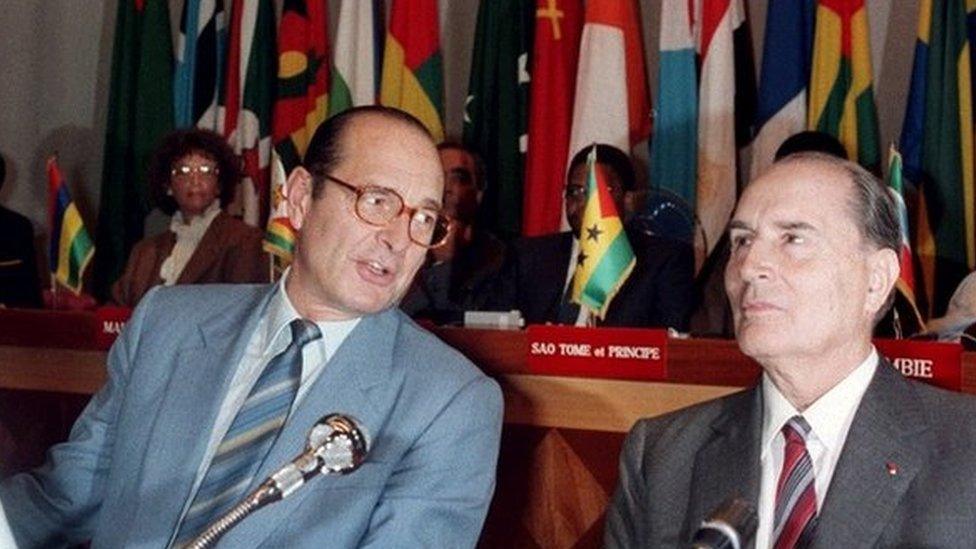

D'Estaing and Chirac: Differences soon emerged between president and prime minister

The 1960s saw him working as an assistant to Gaullist Prime Minister Georges Pompidou.

It was he who marked Chirac out for the top and made him a junior minister in 1967.

In 1974 the Gaullists experienced a watershed year.

Chirac, now firmly at the centre of things, led a revolt against the official Gaullist candidate for the presidency, Jacques Chaban-Delmas, in favour of Valéry Giscard d'Estaing.

Marred

When the latter duly became president he rewarded Chirac with the premiership. He was 41 years old.

Two years later came another split.

Chirac, wanting more powers for himself from the increasingly imperious Giscard, resigned as prime minister and compounded his action by forming his own neo-Gaullist party, the RPR.

In 1977, Chirac was elected mayor of Paris, a post he would hold for 18 years.

The relationship between Chirac and Mitterrand was often strained

But his tenure was marred by numerous financial and political scandals which would sully his reputation.

He had ambitions for the presidency and in 1981 he stood, unsuccessfully, against the Socialist François Mitterrand.

Mitterrand made Chirac prime minister in 1986, during the period of "cohabitation" between left and right, but the relationship between the two was fraught. There were disagreements over the extent to which Chirac felt that presidential powers were encroaching on to his own role as prime minister.

However, Chirac's protests had little impact on Mitterrand, whose own nickname "Dieu" - "God" - revealed much about his own magisterial image.

Chirac suffered a severe setback when striking students forced him to abandon his planned changes to the university system.

He was also heavily criticised for his role in the release of French hostages held in Lebanon in 1988.

Many suspected that Chirac had made a deal with Iran, which was backing the kidnappers, something that he vehemently denied.

After being defeated a few days later by Mitterrand at the 1988 presidential elections, Chirac resigned from the cabinet.

Jacques Chirac defeated Lionel Jospin in the 1995 presidential election

Ever a thorn in the side of the Socialist government, Chirac still believed that his time would come, as French attitudes changed towards taxation, privatisation and the role of the state.

In all of these areas, opinion was moving to the right and the only question was who would pick up the baton.

Chirac's time finally came in the 1995 presidential elections.

With a promise of tax cuts and a healing of the social divide in France, he defeated his main Gaullist rival, Edouard Balladur, in the first round and saw off Mitterrand's Socialist successor, Lionel Jospin, in the second.

Violent demonstrations

At the third attempt "the bulldozer", as Chirac was nicknamed, had finally crashed the gates of the Elysée Palace, ending 14 years of opposition for the French right.

While retaining much of the pomp that goes with the job, Chirac opened up the presidency.

The pavement in front of the Elysée Palace, once a no-go area for Parisians and others, was pedestrianised, and it even became possible to email him directly.

But in other ways there was little change.

Within six weeks of his inauguration, Chirac had outraged world opinion by announcing the resumption of French nuclear tests in the South Pacific.

As the tests took place on Mururoa Atoll, the nearby French territory of Tahiti erupted in violent demonstrations.

Rioting only ended when the president sent in the Foreign Legion.

He also took sharp action against environmental groups, ordering the boarding of a Greenpeace ship which had entered the test area.

Tensions

Chirac continued the policy of close co-operation with Germany, publicly stating that European integration relied upon Franco-German leadership.

He was berated for keeping French interest rates high in order to shadow the Deutschmark.

He said it was the price to be paid for a single European currency, which France eventually joined.

At home, nothing could mask the endemic problems affecting French society.

High levels of unemployment, a growing underclass and increased racial tensions saw the French public become increasingly distrustful of politics and politicians.

The resurgence of Jean-Marie Le Pen's far-right National Front in the 2002 presidential elections, shook French politics.

The elections saw Le Pen and Chirac run off against each another.

While the far-right leader was soundly defeated, the outcome posed more questions about democracy in France than it answered.

Foundered

However, Chirac's reputation was bolstered, for a time, by his implacable opposition to the war in Iraq.

His refusal to involve the French in any invasion outraged many in the United States and drove an immovable wedge between him and Tony Blair, but Chirac remained defiant.

"America has its own stance in this affair," he told the BBC in 2004. "The American president says he will not change his position, which I can understand perfectly. France has hers, and she won't change either.

"This does not mean we are disrespectful towards each other," he added.

Entente Cordiale? The Blair-Chirac rows became the stuff of legend

It was Europe, though, which came to define Chirac's presidency.

His dream of a Europe led by France and Germany foundered as enlargement of the EU brought in new members from the east, radically shifting the old balance of power.

And, despite celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Entente Cordiale in 2004, relations between France and the UK grew increasingly strained, especially over Britain's continuing European budget rebate, with the president venting his spleen at Tony Blair after one fractious EU summit.

"Personally, I deplore the fact that the United Kingdom refused to pay a fair and reasonable share of the cost of enlargement," said Chirac in 2005.

Ailing

The French public's decisive rejection of the proposed EU constitution in May 2005 dealt a seismic blow, both to the country's political elite and to the man whose own legacy was riding on the result.

Immediately after the vote, the visibly cowed president appeared on national television, calling upon the nation to wrap itself in the tricolour.

"Let's not fool ourselves," he said.

"The decision of France inevitably creates a difficult context for the defence of our interests in Europe. We must respond to this by uniting around one requirement; national interest," he added.

EU enlargement ended his dreams of a Europe dominated by France & Germany

Paris's failure in 2005 to win the competition to host the 2012 Olympics was symbolic of the loss of confidence in Chirac's administration.

His second term as president came to an end in 2007, and four years later the ailing former leader was convicted of corruption relating to his time as mayor of Paris.

A nationalist in the Gaullist tradition, Jacques Chirac was a man of great political ability who brought charisma and personal charm to his role.

His critics dubbed him "the weathervane" but, after a career lasting 40 years, the political climate had changed and his own skills, once formidable, had waned.

However Jacques Chirac was a political survivor and although his time was up in 2007, he could still lay claim to one of the longest continuous political careers in Europe.