Obituary: John Demjanjuk

- Published

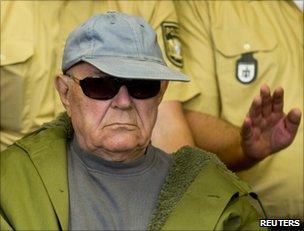

John Demjanjuk arrived for his German trial at the age of 90

John Demjanjuk, an elderly former Ohio car worker who was born in Ukraine, was finally convicted of Nazi war crimes after decades of fighting attempts to bring him to justice.

Before his latest trial, in Germany, he was famously deported from the US to Israel in 1986 to face allegations that he had served as a camp guard nicknamed Ivan the Terrible at Treblinka.

He was convicted and sentenced to death. But he was reprieved a few years later after new evidence appeared.

But back in America, decades later, an immigration judge ruled there was enough evidence to prove he had been a guard at other Nazi camps, and he was sent abroad for trial again in 2009.

The Munich case, in which he was given a five-year jail sentence, is expected to be Germany's last big war crimes trial.

War years

Born Ivan Demjanjuk on 3 April 1920 in the Ukrainian village of Dubovi Makharintsi, he was raised under Soviet rule.

A burly man, he worked as a tractor and lorry driver on a Ukrainian collective farm.

Little can be said with certainty about Mr Demjanjuk's activities during World War II.

He joined the Red Army like millions of others, and was serving in eastern Crimea in 1942 when he was captured by the Germans.

At least three million Soviet soldiers are believed by historians to have died in German prison camps, many of them left to starve. "I would have given my soul for a loaf of bread," Mr Demjanjuk said later in court.

At his trial in Israel, he testified that he had been held at a camp in Chelmno, Poland, until 1944 before being moved to another camp in Austria where he joined a Nazi-backed unit of Russian soldiers fighting communist rule.

But according to German prosecutors, between March and September 1943, he was in fact involved in the murders of tens of thousands of Jews at the Nazis' Sobibor death camp in Poland.

They said they had obtained hundreds of documents and a number of prosecution witnesses.

"For the first time we have even found lists of names of the people who Demjanjuk personally led into the gas chambers," said Kurt Schrimm, head of the special office investigating Nazi crimes.

First trial

After the war, Demjanjuk lived in southern Germany, working as a driver for various international refugee organisations, according to Germany's Spiegel magazine.

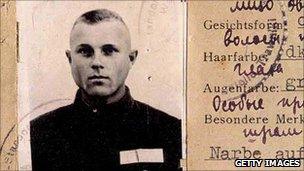

The defence said that the SS ID card was a forgery

In 1952, he emigrated to the US with his wife and child, eventually settling in Cleveland, where he worked as an engine mechanic at a car plant.

He was naturalised as a US citizen but his citizenship was temporarily removed after a US judge ruled in 1981 that he had lied in his citizenship application about his wartime activities.

Israeli prosecutors requested his extradition in 1983. They believed Mr Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible - one of the most infamous guards at Treblinka.

Ivan had helped operate the gas chambers and personally murdered hundreds of prisoners, hacking many of his naked victims to death with a sword, according to witnesses.

A US court rejected his appeal against deportation in 1985. The court dismissed doubts cast over the authenticity of an ID card, which the defence said was a forgery.

The card showed that Mr Demjanjuk belonged to the Trawniki unit - an SS-trained section of non-German volunteers which was tasked with persecuting and murdering Jews.

In Israel, Mr Demjanjuk's lawyers argued that he was the victim of mistaken identity and challenged the accuracy of the memories of five Treblinka survivors who identified him as Ivan the Terrible.

However, the Trawniki ID card helped sway judges in the prosecution's favour and in 1988 he was found guilty of crimes at Treblinka and sentenced to hang.

Five years later, the conviction was quashed in 1993 by Israel's Supreme Court, after evidence emerged in post-Soviet Russia that another Ukrainian - Ivan Marchenko - had in fact been Ivan the Terrible.

However, Israel's chief justice was careful to avoid declaring Mr Demjanjuk innocent, noting that there was ample evidence that he had served as a guard in other camps.

Second trial

Mr Demjanjuk had his citizenship restored upon his return to the US as a free man but in 2002 it was revoked once again.

A district court judge ruled that there was sufficient reliable evidence to prove that he had been a concentration camp guard, if not at Treblinka.

Appeals followed but a court eventually ruled that he should be deported to his native Ukraine, Germany or Poland.

In November 2008, state prosecutors in Munich announced they had enough evidence to prove his involvement in the murders of Jews at Sobibor.

He was formally charged in Germany with 27,900 counts of being an accessory to murder.

He fought extradition - protesting that he was too ill to travel. He turned up in court in a wheelchair or lying motionless on a stretcher. But the court was shown secretly recorded evidence of him walking unaided, and ruled against him. He was deported to Germany in May 2009.

His defence there again questioned the authenticity of the Trawniki ID card - but the German court rejected its request to suspend the trial.