Divorce in Malta: Referendum causes acrimonious split

- Published

Polls suggest the referendum race is neck and neck

The close-knit community on the Mediterranean island of Malta could be on the verge of a fundamental change that may affect the very fabric of its society.

In a referendum on Saturday, the citizens of this deeply Roman Catholic country will decide whether to introduce divorce.

Malta is the only country - apart from the Philippines and the Vatican City - where divorce cannot be carried out.

Instead, people must either become domiciled abroad or, if one of the parties is not Maltese, they could apply for a divorce in their own country. That divorce can be recorded in Malta.

Couples can apply for a legal separation through the courts, or seek a Church annulment - a complex process that can take up to nine years.

Anti-divorce campaigners argue that the institution of marriage is strong in Malta precisely because couples do not have the option of a fall-back position. And they say that this helps make Maltese society one of the closest-knit in the world.

But those who are pro-divorce say that there are already plenty of separations in Malta, and that these people should be allowed to marry again.

Two camps

According to the Labour opposition leader Joseph Muscat - who is in favour of divorce - two legal separations a day pass through the Maltese courts. On top of this, the courts regularly record foreign divorces.

With at least 95% of a population of more than 400,000 being Roman Catholic, divorce has never made it past the strong religious beliefs of the Church, politicians and the public itself.

But that might be about to change. Last year Jeffrey Pullicino Orlando, an MP with the Nationalists, presented a private member's bill along with Evarist Bartolo, an MP with the opposition Labour party.

This bill proposed that people could divorce after living apart for four years, and as long as spouses and dependents were provided for.

Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi's suggestion of a referendum sparked an impassioned debate.

The Catholic Church and the ruling Nationalist party are both backing the "No" campaign, while the Labour party has not taken an official stance.

Role of Church

Mr Orlando, speaking at his large and immaculate home in the countryside around the town of Zebbug, says he did not believe that new legislation would contribute to marital breakdown.

"It's simply a bill that will help regularise the situation for a lot of couples, who are being forced to cohabit," he says.

Jeffrey Pullicino Orlando, an MP with the Nationalists, thinks the current system is unjust

Separated from his own wife, he has said that he will seek divorce abroad if it is not introduced in his own country. But he points out that this is not something many Maltese can do.

"Malta is the only country in the world which doesn't have divorce but does recognise those obtained abroad. Therefore, if you have the means you can get divorced but if you don't, then you can't.

"This, to me, is unjust and unacceptable."

Mr Orlando sees the referendum as more than just a vote on divorce - for him it's a debate on the Church's role in society and the amount of political and social influence that it carries in Malta.

"I appreciate the fact that the Church should be allowed to exercise spiritual influence, but I can't accept a situation where the Church also wields political and administrative power," he says.

Some parishioners say they have been told by their priests that they will be denied Holy Communion and confession if they vote for divorce, he continues.

"The local Catholic Church is going to suffer, even after the referendum."

Conflict

There have been two recorded cases of conflict between Church and public - one priest who regularly gave the Eucharist to an elderly woman at home began to withhold it once she told him she was pro-divorce. She later received it from another priest.

And, on a recent Sunday, a priest announced to his congregation that anyone planning to vote for divorce in the referendum should not come up to receive Holy Communion - sparking a walk-out by some of his flock.

But Monsignor Anton Gouder, a senior official within the Maltese Archdiocese, says that the two cases were isolated, and that at least one of the priests has apologised.

He also confirms that, despite comments made by other senior priests suggesting otherwise, those who vote for divorce will still be able to go to confession and Holy Communion.

He says divorce is not a religious issue, but a social one, describing Malta as one of the strongest countries in the world for family, with some of the happiest children.

"Not to have divorce is special in a positive way. Statistics show that divorce brings much more marriage breakdown and more cohabitation," he says.

"The fact that we don't have divorce in Malta has helped to strengthen marriage here. Most Maltese marry, and most do that in church.

"With divorce, marriage for life ceases to exist. Your youngsters, who have grown up with divorce, don't know what that actually means in practice."

Neck and neck

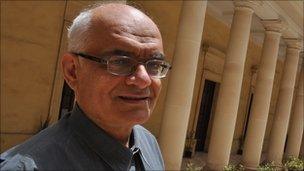

Anton Gouder thinks Malta's stance over divorce has made its society something worth preserving

Mgr Gouder acknowledges that the Church has been damaged by the debate, which has spilled over into questions about how much influence religion should have in a society that is officially secular.

"Obviously, as in other countries, when there is a moral issue at stake, some parts of society find it useful to attack the Church, so that if the Church loses credibility, more people will vote against the principles that the Church holds."

Polls suggest the referendum race is neck and neck. A result is expected on Sunday, but either result may not yet see an end to the argument.