Italy elections: Voters give Berlusconi bloody nose

- Published

- comments

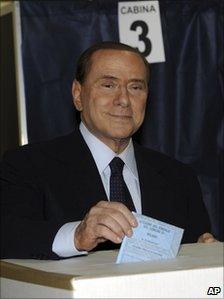

The polls became a referendum on the 74-year-old leader

Any way you slice it, Silvio Berlusconi is the big loser in the local elections in Italy. His coalition has lost Milan, his home turf, the city where he built his empire. To lose Milan, in his view, was "unthinkable".

So these elections became a referendum on the 74-year-old Italian leader. It also seems his party lost the city of Naples where even last week he was attempting to weave his old magic with the voters. It has not worked.

Milan has been run by conservative mayors for two decades. It has been a bitter campaign.

Silvio Berlusconi and his allies raised the spectre that a victory for the left would have handed the city over to Gypsies and Islamists.

"If Pisapia (the leftist candidate) wins," he said, "Milan will become a Muslim town, a Gypsyville of Roma camps, a city besieged by foreigners." The voters were not persuaded.

This seems to be the moment when Italians expressed their weariness with the sex scandals, the gaffes, the never-ending battles between the Italian prime minister and the judges.

He recently lashed out at the magistrates as a "cancer". He even complained to US President Barack Obama about the leftist judges.

It had long been presumed - even after accusations of sex with an under-age prostitute - that if there was an election, Mr Berlusconi would once again emerge the winner. Not any more.

'Changing mood'

Tomorrow the trial resumes in the case of Ruby, the woman he is accused of having under-age sex with.

There are three other corruption trials under way. Too much of Italian public space has been taken up with the private trials and scandals of the man called "il cavaliere".

What this defeat could do is sow discord with his allies, the Northern League.

They were critical of his campaign and may question whether their alliance with Mr Berlusconi's party is damaging them, even in a northern stronghold like Milan.

And without the Northern League, the Italian prime minister will not survive. This rejection by the voters may well undermine the Italian government.

Mr Berlusconi's instinct will be to fight on. It always is.

His allies, such as the Defence Minister Ignazio La Russa, said: "I don't see any possibility of an alternative government. And I don't think anyone wants early elections."

All true, but his allies sense the mood has changed in the country.

It is not just a question about scandals. Italy's economy remains sluggish.

A quarter of young people are without work.

And recent elections in Europe show that the incumbents are being punished.

In that climate, Mr Berlusconi's allies might seek a separation and bring to an end to the political career of the man who has dominated Italian politics and Italian public life for 15 years.