Viewpoint: Hague tribunal justice 'works'

- Published

The court decided to go after 'those most responsible' - the leaders

Former Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladic is now in The Hague, where he will go on trial at the international war crimes tribunal. Will justice be delivered?

Judge Richard Goldstone, former chief prosecutor for the Yugoslavia and Rwanda tribunals, believes the court has set important benchmarks. He held the posts from 1994-96, when indictments were drawn up against Gen Mladic and his political boss, Radovan Karadzic.

When in 1994 I started investigating war crimes in the former Yugoslavia I could not have imagined that the process would be so complex, slow and yet so successful.

The contrast with the 1945 Nuremberg Trials of the Nazi leaders is a stark one. Each of the four Nuremberg chief prosecutors worked with his own team. There was no multi-national office of the prosecutor. I arrived in The Hague on 15 August 1994 as effectively the first chief prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

My task was to set up the first ever international prosecutor's office. There was really no precedent for it. The inordinate delay in the UN Security Council appointing a chief prosecutor resulted in a negative public perception of the ICTY, and if we were to garner funding from the cash-strapped UN we had to show very quickly that the endeavour could succeed.

The first indictment was against a middle-ranking Serb army officer, Dragan Nikolic, the commander of a notorious detention camp. The indictment was issued within two months of my arrival. Nikolic was apprehended in 2000 and after pleading guilty to serious crimes was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment.

Indictments

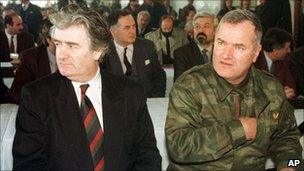

The policy we adopted in the Office of the Prosecutor was to investigate those most responsible for the horrendous war crimes committed during the war in the former Yugoslavia. That meant going for the leaders. In April 1995 we named the so-called president of the Bosnian Serb entity of Bosnia Hercegovina, Radovan Karadzic, and his army commander Ratko Mladic as suspected war criminals, even as the siege of Sarajevo was still going on.

But, in the second week of July 1995, the horrendous slaughter of some 8,000 men and boys was carried out by the Bosnian Serb Army at Srebrenica. This was the worst act of genocide committed in Europe since the end of World War II. In the Prosecutor's Office, we were disappointed and even disillusioned that, notwithstanding the naming of Mr Karadzic and Gen Mladic as suspected war criminals in April, they appeared not to be deterred from slaughtering more innocent civilians at Srebrenica.

Some two weeks after the massacre, both men were charged by the ICTY with crimes against humanity and other serious war crimes. The most egregious of these crimes was the murder of children, women and men innocently going about their business in Sarajevo at a time that the Bosnian Serb Army was conducting a cruel siege of the city.

On 16 November, 1995, both Mr Karadzic and Gen Mladic were indicted a second time on charges that included genocide relating to the events in Srebrenica. The two indictments have been amended from time to time and it is the charges contained in them that Mr Karadzic is facing at present in The Hague and that Gen Mladic will face very soon.

Like any human institution, the ICTY has had its successes and failures. It will always be a matter for regret that Slobodan Milosevic, the former president of Serbia, did not survive an over-long prosecution and died in a prison cell of the ICTY.

That said, the successes of the ICTY have been important - the fair trials of many war criminals from Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia Hercegovina, and the conviction and imprisonment of many of them.

These proceedings have undoubtedly brought acknowledgement and some solace to many thousands of victims. I had the privilege of meeting some of them during a visit to the former Yugoslavia at the end of 2010.

'End of impunity'

The proceedings have also put an end to many of the fabricated denials that followed the commission of serious war crimes. In the aftermath of the Srebrenica massacre the official policy of the Bosnian Serb Army was to deny the killings and to ascribe the allegations to dishonest propaganda.

Mr Karadzic and Gen Mladic had already been indicted when the Srebrenica massacre occurred

The exhumation of the mass graves, the evidence of victims and satellite photographs furnished by the United States put an end to those denials. Today, most people in the former Yugoslavia accept that there were victims and perpetrators on all sides. That is important if there is to be any final reconciliation between the peoples of that region.

The successes of ICTY were also responsible for the subsequent establishment of the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, mixed tribunals for East Timor, Sierra Leone, Cambodia and Lebanon and, most important of all, the International Criminal Court. These developments have signalled the end of effective impunity for the worst war criminals.

It is in the shadow of the ICTY that there are proceedings currently in progress against Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, that there is an arrest warrant awaiting execution against the President of Sudan, Omar Bashir and that the prosecutor of the ICC has requested its judges to issue an arrest warrant for Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader.

It is my hope that the leaders of Sri Lanka and Syria will not be granted immunity for the crimes they are alleged to have committed against innocent civilians in their countries.

The arrest in the past few days of Gen Mladic must cause added discomfort for others alleged to have committed serious war crimes.

They must be concerned that eventually they will be brought to account before relevant domestic or international courts and will have to answer to many tens of thousands of victims for the crimes alleged to have been committed by them.