No to nuclear and no to Berlusconi

- Published

- comments

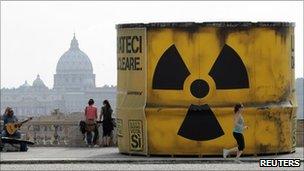

Anti-nuclear protesters erected this giant mock nuclear waste barrel in Rome

In the past two days the people of Italy have been given their say.

They have convincingly rejected nuclear power and they have delivered another humiliating defeat to Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

The disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan is changing Europe's energy future. Increasingly it looks as if it may become a continent without nuclear power.

The French have bet heavily on the nuclear industry providing clean energy. Given the chance, Europe's citizens are saying "no way".

Eyes on France

On 30 May, Germany, Europe's economic powerhouse, decided to phase out atomic power between 2015 and 2022. Switzerland looks set to follow. It is examining a proposal to phase out the country's nuclear plants by 2034.

Now Italy will not revive its nuclear industry. The people have spoken and spoken convincingly.

Silvio Berlusconi had urged his supporters to boycott the polls, hoping that the turnout would not reach the necessary threshold of 50%.

In the end, 56% of voters took part and afterwards the prime minister conceded: "We will have to commit strongly to the renewable energy sector."

The leader of the Greens in the European Parliament, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, said this vote "could open a serious phase of reflection in other member states".

If Europe moves away from nuclear power, a question arises as to whether it can fill the gap with renewable energy. Will the mood in France change and will they, too, get a chance to vote?

Evaporating magic

Silvio Berlusconi looks more and more isolated

There was a second plot to the vote in Italy: Silvio Berlusconi himself. Last month, in elections he made about himself and his authority, his candidates were badly beaten. Now he has suffered a serious defeat on a number of referendum questions.

The public rejected plans to privatise the water system. Even the Vatican got involved, declaring that water was a human right and should not be subject to market forces.

Most significantly, the people rejected a change in the law that would have enabled the Italian leader and other high officials to avoid prosecution.

Berlusconi's appeal to the Italian electorate, which has long survived gaffes and scandals, is now ebbing away.

The magic has gone. That bond between Berlusconi and ordinary Italians seems to have snapped. Perhaps voters have become weary of a leader where so much of public debate is about his personal life and his political survival?

Pierluigi Bersani, leader of the main opposition Democratic Party, was calling on Mr Berlusconi to resign. "This referendum," he said, " was about the divorce between the government and the country."

Berlusconi still has a majority in parliament but it is dependent on the Northern League. They are now questioning whether their alliance with Berlusconi's party is damaging them. Some may decide it is time to break away.

Next week there were be a vote on confidence in the Italian parliament. It is not in Mr Berlusconi's character to step down but he is increasingly an isolated figure. He has a fragile majority in parliament but almost certainly not in the country.