Italy's Northern League reviews support for Berlusconi

- Published

Padania power: It was the Northern League which brought down Berlusconi's government in 1994

Italy's Northern League has been a strong supporter of Silvio Berlusconi - and in return, it wants more autonomy for the North. But, with the prime minister's future looking ever more uncertain, League supporters are getting increasingly restive, as the BBC's Mark Duff discovers.

The old men playing cards outside the Bar Acli do not seem to notice the lorries thundering through their village.

Pontida - population 3,000 - lies slumped in a cleft where the last Alpine foothills meet the vast flatness of the Po valley.

For 364 days of the year, the card players have the place to themselves.

On one summer's day each year, though, they have to make way for up 40,000 boisterous supporters of the Lega Nord, or Northern League.

It is a sight like no other: A field of green - the colour of the League; green shirts, green sunshades; even old men with their beards dyed green.

Pontida is sacred to the League. Tucked around the corner from the bar is the reason why: the Benedictine abbey church of San Giacomo Maggiore.

Legend has it that here, in 1167, the lords of northern Italy committed themselves to defend each other from invasion.

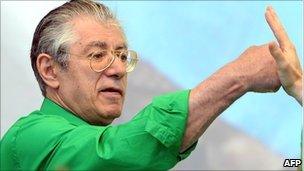

Northern League leader Umberto Bossi's supporters are starting to demand results

Then the threat was from the Holy Roman Empire. Today - for the Northern League - it is lazy, corrupt southerners; a greedy administration in Rome; and boatloads of desperate people seeking refuge from the turmoil in North Africa.

But all is not well in Padania, as the League calls its northern heartland.

Not so long ago, the party was riding high in the polls. Its ally, Silvio Berlusconi, looked like the Teflon man of Italian politics.

But two drubbings at the polls in as many weeks have changed all that. The rumbles of discontent from the rank and file have become as noisy as the trucks trundling through Pontida.

The Northern League is a workers' party, faithful to its regional roots in Lombardy, Piedmont, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Liguria.

'Roman' insult

Its bedrock lies among the small family firms whose hard work has made this part of Italy one of the wealthiest regions in Europe.

It is also strong among the workers at places like the vast steel plant at Dalmine, just down the road from Pontida. All these groups have been hurt by the economic downturn.

The League claims to be a broad church.

"We have many people from the left and right," says Paolo Grimoldi, who heads the League' s youth section. "The Lega Nord is a movement, more than a party - a kind of trade union of the North."

The Northern League's quest for secession has faded, but not disappeared

Some leghisti - like one of the League' s new generation of leaders, the young and outspoken MEP, Matteo Salvini - are beginning to suggest that Silvio Berlusconi has become an electoral liability.

Others say the movement's own leadership has become too comfortable in Rome, has become too "Roman" - an insult to make the most hardened leghista shudder.

There have even been unprecedented mutterings about the League's ageing leader, Umberto Bossi.

Among the traditional flags and banners this year were placards demanding actions not words, and a return to the simple truths of freedom and legality.

There were almost as many cheers for the chant of "secession" as there were for Mr Bossi himself.

Shutters come down

The grass roots are fed up. For 20 years, they have been drip fed promises of greater autonomy and tax cuts; now they want to see the beef.

Hence the demands set out last week by one of the League' s most able leaders, the Interior Minister, Roberto Maroni: for tax cuts to help small businesses hard hit by the recession; and for an end to Italy's involvement in overseas missions to Libya and Afghanistan.

The leghisti did not let their political frustrations dampen the party mood at Pontida. It was noisy, boisterous and mainly good-natured.

There were only occasional glimpses of the League's well-known hostility to immigrants, as when a woman party apparatchik followed her leader to the podium and yelled: "We shouldn't have to look after these immigrants. We want to look after our old people, our unemployed. These immigrants aren't our responsibility."

Grass-roots supporters were drip fed promises; now they want concrete results

Such sentiments are not uncommon. Italians simply are not used to mass immigration - and even broad-minded ones sometimes say things that make a politically correct north European shudder.

The people of Padania grumpily flout the cartoon stereotype that sees Italians as incontinently emotional, friendly and open. They are hard and tough, and can seem closed - "chiuso".

A local priest, who helps immigrants find their feet, explained the reality thus: "It's all about the economy. In good times, the locals don't have a problem with immigrants. They know that cheap, foreign labour keeps the cash tills ticking over. But when times are tough - as now - the shutters come down."

Those chants of "secession" at Pontida harked back to the golden days when the League' s ultras dreamed of little else.

But the realists have a more pragmatic goal now - federalism, including greater control of their own regions' finances.

Fiorello Provera is a Northern League MEP, and vice chairman of the European Parliament's foreign affairs committee.

"If we can make federalism work", he says, "secession will simply no longer be on the agenda."

But he adds that Silvio Berlusconi has at most eight months to deliver, or risk losing the League' s support.

Umberto Bossi is unlikely to desert his old ally just yet. Federalism is Mr Bossi's Holy Grail, and he knows that an increasingly desperate Mr Berlusconi remains his best hope of delivering it.

But the dour people of Padania are in a febrile frame of mind. Mr Berlusconi will not need reminding that it was the Northern League which pulled the plug on his first government in 1994.

He will not want to repeat the experience.

- Published17 June 2011