Sweden's 'gender-neutral' pre-school

- Published

- comments

The playground has become the latest battleground in Sweden's drive for gender equality

Some have called it "gender madness", but the Egalia pre-school in Stockholm says its goal is to free children from social expectations based on their sex.

On the surface, the school in Sodermalm - a well-to-do district of the Swedish capital - seems like any other. But listen carefully and you'll notice a big difference.

The teachers avoid using the pronouns "him" and "her" when talking to the children.

Instead they refer to them as "friends", by their first names, or as "hen" - a genderless pronoun borrowed from Finnish.

Changing society?

It is not just the language that is different here, though.

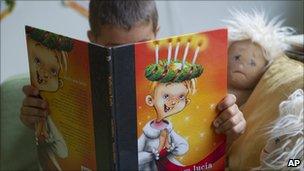

The books have been carefully selected to avoid traditional presentations of gender and parenting roles.

So, out with the likes of Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella, and in with, for example, a book about two giraffes who find an abandoned baby crocodile and adopt it.

Most of the usual toys and games that you would find in any nursery are there - dolls, tractors, sand pits, and so on - but they are placed deliberately side-by-side to encourage a child to play with whatever he or she chooses.

At Egalia boys are free to dress up and to play with dolls, if that is what they want to do.

For the director of the pre-school, Lotta Rajalin, it is all about giving children a wider choice, and not limiting them to social expectations based on gender.

"We want to give the whole spectrum of life, not just half - that's why we are doing this. We want the children to get to know all the things in life, not to just see half of it," she told BBC World Service.

All the staff are clearly passionate about this.

Teachers say the aim is to help both boys and girls

"I want to change things in society," says 27-year-old Emelie Andersson who is fresh out of her teacher training, and specifically chose to work at Egalia because of its policy on gender.

"When we are born in this society, people have different expectations on us depending if we are a boy or a girl. It limits children.

"In my world, there is no 'girl's world' and there is no 'boy's world'," she says.

Identity politics

Last year a Swedish couple, external provoked a fuss in the media by announcing that they had decided to keep the gender of their young child, Pop, a secret from all but their closest family members.

There was a similar case recently in Canada with a baby called Storm.

But is it not confusing for a young child to blur gender boundaries like this?

It is a criticism that Egalia director Lotta Rajalin has heard many times before, but she contests it vigorously.

"All the girls know they are girls, and all the boys know that they are boys. We are not working with biological gender - we are working with the social thing."

The verdict of child psychologists and experts in gender is divided - with most supportive of the aims, but questioning the means.

"The sentiments are excellent, but I'm not sure they are going about it in exactly the right way," says British-based clinical psychologist Linda Blair.

"I think it's a bit stilted. Between the ages of three and about seven, the child is searching for their identity, and part of their identity is their gender, you can't deny that," she told BBC World Service.

Gender obsessed?

But Sweden takes gender issues seriously, and for a number of years now, the government has been taking its battle to the playground.

Gender advisers are now common in schools, and it is part of the national curriculum, external to work against discrimination of all kinds.

Sweden is often praised as being one of the most equal countries in the world when it comes to gender, but there are critics at home who think things have gone too far.

"This equality idea, it has become so absurd, it has become a really stupid industry," rails Swedish blogger Tanja Bergkvist, who argues that the nation has an unhealthy obsession with gender.

"Gender researchers have convinced politicians that the solution to all problems is a gender perspective.

"That's quite dangerous because they spend money and resources on the wrong things."

The Egalia school - which is state-funded - is proving popular though, and boasts a long waiting list.

Pia Korpi, a metal designer, and her husband Yukka, a dancer and choreographer, have two children at the pre-school.

Ms Korpi says she, and her husband in particular, had to battle to pursue their chosen interests because they sat uneasily with gender expectations, and they want their children to feel free from these restraints.

She says most of their friends and family are 100% behind them, but admits some people might not understand their choice. "People who don't know what this is about - and especially in the countryside - they think it's brainwashing."

Swedish way

The idea of working with children in pre-schools - between the ages of one and five years old - is to help shape them from a young age, but many doubt there are any lasting effects.

Egalia is the Swedish word for equality

"It's a real world out there - we cannot isolate people from that real world," says clinical psychologist Linda Blair.

Philip Hwang, Professor of Psychology at the University of Gothenburg - who has conducted long-term studies of children's development - chuckles slightly when talking about this scheme.

"I don't think it's anything bad," he says.

"But it is naive to say the least. It is a symbolic gesture. I find it a bit funny - who do they think they are fooling?"

"It's very Swedish in a sense. Swedes have a tendency to think that if they institutionalise something, it will automatically change - it's the Swedish way," he told the BBC.

"But lasting effects - when it comes to issues embedded in our culture - that takes generations."

- Published9 May 2011

- Published17 October 2010

- Published12 October 2010