Chechnya's long wait for the disappeared to return

- Published

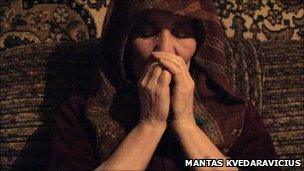

The family of Hamdan Mastaev, abducted in March 2008

For visitors today to Chechnya's bustling capital, Grozny, war already seems like a distant memory. But thousands of Chechens are still waiting for relatives who disappeared in the war to return - their hopes boosted by traditional beliefs about life and death.

Travellers returning from Grozny marvel at the transformation of the city.

Eleven years ago, after Russia's second military operation to bring the republic under central control, it stood in ruins. Today it's a place of busy cafes, smart shops and new high-rise buildings.

Yet scholars note that the war-inflicted wounds in Chechen society are not healing.

Thousands of families cannot accept that loved-ones who disappeared may be dead - either because there has been no official confirmation of death, or because of the Chechen belief in the power of dreams.

Relatives believe they connect with lost family members through dreams, and this hinders the process of mourning and moving on.

As long as one family member can dream of the missing relative, the whole family feels his or her presence in their daily life.

Fortune tellers

The subject has been studied by Cambridge University social anthropologist Mantas Kvedaravicius, who spent long periods in Chechnya between 2007 and 2009 and shot a film that was premiered at this year's Berlin Film Festival.

"He comes to me each night, he is present in my life, his presence gives me joy," says one mother quoted by Kvedaravicius.

Another mother dreams of three people sleeping in a room. Two of them are her surviving sons, and the third bed, she reasons, must be occupied by her missing son.

"I want to lift the blanket, but I dare not look," she says. "I think if I look my heart will break. Better I should think that there lies my Rustam."

A third mother has a more puzzling story.

"I dreamed of my son and he had a hurt leg and he asked me for his shoes," she says. "I had old galoshes, which I took - and I broke one, and gave my son one-and-a-half."

The mother of Alik Tazuev, who was abducted in July 2002

Such dreams are treasured and discussed in detail with friends, family and fortune tellers, to determine the loved-one's whereabouts and state of health.

Before the family receives proof of death, even a brief thought of the missing person as dead would cause a feeling of guilt, as if it were a betrayal.

"Families talk about their missing members daily, and always in the present tense," says Chechen historian Maerbek Vachagaev.

"When I am visiting, I always ask for news of the disappeared. Sometimes I am certain that the missing person is no longer alive, and his family's hopes are futile. But I would not dare suggest it.

"'Who are you to know that our son is dead? How can you be so sure?' they would reply."

Hopeless search

Outside Chechnya, it is generally understood that the vast majority of those who disappeared are dead.

A Chechen divining with stones - each stands for a person, or for ideas such as joy, prison, or death

But Chechen and Russian officials are rarely able to give confirmation of death.

It is impossible for Chechen officials even to acknowledge cases of disappearance, unless they can be blamed on Russian federal troops. Nearly all Chechens avoid talking about abduction or torture by Chechen security forces, for fear of punishment.

The myth of Chechen prisoners stuck somewhere in Russian jails is therefore free to circulate.

Mantas Kvedaravicius accuses Chechen officials of promoting what he calls the cruel "politics of hope".

"This is a way of keeping someone at bay," he says.

"Not only the years of family life lost in the hopeless search, but the very absence of the death and the recognition of this absence, cause individuals to collapse from inside."

He compares the state of the disappeared relatives with the concept of Barzakh, in Muslim teaching - a state between life and death, where souls rest until the day of resurrection.

In the words of one mother: "I hear a sound at night. I wake up. I look through the window and there is nothing. I do not have him alive, and I do not have him dead."