Fate of Franco's Valley of Fallen reopens Spain wounds

- Published

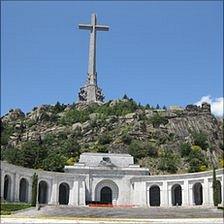

Gen Franco's Valley of the Fallen is a rallying point for the far right

In the hills outside Madrid there is a striking symbol of four decades of dictatorship.

The Valley of the Fallen is the vast monument General Francisco Franco commissioned to commemorate his victory in the Spanish Civil War.

Seventy-five years after that war began, there are finally plans to change this landmark.

At its heart is an enormous basilica, scooped out of the hillside. Franco himself is buried behind the altar, beneath a gravestone decorated with fresh flowers.

The Valley has long been a rallying point for the far right in Spain, built to exalt the armed nationalist uprising Franco led against the elected Republican government, his "glorious crusade".

Now the Socialist government is considering exhuming the dictator's remains in order to transform the site into a place of reconciliation.

'Prudence'

Even 36 years after Franco died the government minister in charge admits that is a delicate task.

"Spain's transition to democracy was an act of prudence after the deep wounds caused by the war and the dictatorship," Ramon Jauregui explains.

"We have dealt with the past little by little. Maybe we're tackling this site a little late, but prudence has been the key to our peaceful transition."

Spain held no truth and reconciliation process after the war; there was no accounting for crimes, or punishment. The country agreed to "forget" and look to the future, for the sake of peace.

But as the fear has faded, that approach has been changing.

For the past decade, archaeologists and volunteers have been exhuming the remains of Republicans from unmarked graves. (The bodies of most of those who died fighting for Franco were recovered long ago.)

Then in 2007, the government passed the Historical Memory Law, granting victims of the war and dictatorship formal rehabilitation and compensation. All remaining monuments to Francoism were to be removed.

But Spain's conservative opposition party, the PP, refused to back the bill. There was talk of opening up old wounds.

"There are people in Spain who are afraid of being confronted with the darkness of the past," explains historian Angel Vinas.

"There were horrors committed here, massacres. But we're not unique in that and other countries have come to terms with it. I don't see why Spain should not," Mr Vinas says.

For him, reforming the Valley of the Fallen is all part of the process.

Hidden past

The monument was one of the most visited sites in Spain. But it has no signs explaining its history and no mention that it was built largely by political prisoners.

One suggestion is to move Franco's remains to a more modest site

Nicolas Sanchez Albornoz was one of them - a student activist sentenced to six years in a labour camp for "activities against the state". He escaped in 1948 and has never been back.

"I think it is really shocking that in a European country you still have a huge monument to the memory of one of the bloodiest dictators," says Mr Sanchez, now in his 80s.

"The best thing to do is to remove all the symbolism [from the site]. And what gives such force to that symbolism, is the presence of Franco."

The government is waiting for an expert commission to deliver its proposals before deciding.

But one suggestion is to transfer Franco's remains to a modest, municipal cemetery beside his wife. His daughter has already objected, and the Franco Foundation she heads has vowed to take legal action to prevent it.

"A huge number of people will oppose this barbarity," insists Jaime Alonso, in a room plastered with photographs of Franco, and a life-size portrait. He argues the general's revolt saved Spain from the clutches of Soviet Russia.

"They can't move Franco without his family's permission, that would be desecration. You have to be careful with history in Spain. You can't demonise one part of society and praise the other. That's wrong and achieves nothing," he warns.

Government's challenge

Few Spaniards are so open in their admiration of Franco. But many voice the same aversion to moving his grave.

"It's a ridiculous idea, after all this years," says Jose Luis, on a visit to the Valley of the Fallen. "That way we'll just keep the war going!"

"This is just tampering with the past," Jorge agrees. "And the monument is very beautiful."

For the losers in the war, though, it's quite the opposite.

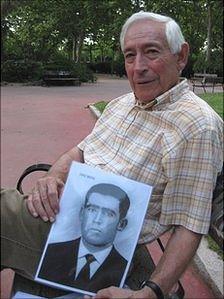

Fausto Canales' father was shot by Fascists, and his remains are in the Valley

In August 1936, Jorge Valrico Canales was taken from his home in the middle of the night and shot by a Fascist execution squad. His town had fallen to the uprising and he had been singled out as a socialist.

In 1959, his remains were dug from a well and moved to the Valley of the Fallen. More than 30,000 war dead from both sides were transferred there on Franco's orders.

"For me, it's excruciatingly painful that my father's remains are in a place built to the glory of the victors in a military coup," says Fausto Canales. "It feels like a double crime. First when he was executed, then when they moved his body without our permission to a place which is totally inappropriate."

The family is one of a group now demanding they be permitted to exhume their relatives' remains for a proper burial, though a study suggests that might be impossible now.

The challenge for the government is to transform the divisive monument into one for all Spaniards.

"Changing perceptions is not easy," Ramon Jauregui admits. "But if this place is to have a future it must be in remembrance of the horror of the war and all its victims."

Seventy-five years on, that would be the first of its kind here.

- Published18 July 2011

- Published28 June 2011