Is Sarkozy on a culture drive?

- Published

French President Nicolas Sarkozy has apparently been flaunting a love of culture - but how genuine is it?

In his excellent recent biography of Sarkozy, the journalist Franz-Oliver Giesbert recounts how the president's cultural life has been transformed by Carla Bruni.

The old Sarkozy was a boor. He gleefully displayed his contempt for France's arts establishment and his preference for the crass.

He appeared only to have ever read two books - Louis-Ferdinand Celine's Journey to the End of the Night and Albert Cohen's Belle du Seigneur. Of modern literature he knew not a thing.

"You would have said that his culture - if you could call it that - was purely televisual," writes Mr Giesbert.

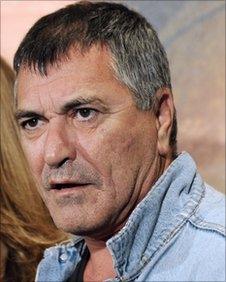

Comedian Jean-Marie Bigard, a friend of Sarkozy, has mass appeal

The stories about President Sarkozy's supposed cultural ignorance have long done the rounds.

How the headline act at his inauguration concert was the naffest of crooners Gilbert Montagne.

How on once leaving the French state theatre La Comedie-Francaise, he made a hand gesture to indicate the extent of his boredom.

How he took the coarse comedian Jean-Marie Bigard to an audience with the Pope, and how he complained that civil service exams included questions on 17th century literature.

This was a Sarkozy who knew he was despised by the Paris cultural elite, and decided to give back as good as he got.

Then along came Carla.

For Franz-Oliver Giesbert - who edits Le Point news magazine and is one of the most distinguished observers of the French political scene - the Italian singer-cum-model is the best thing that ever happened to the president.

Not only has she "taught him good manners" and generally "calmed him down", she has also opened his eyes to culture.

Nowadays, the presidential couple apparently spend their evenings watching films and reading.

Where the old Sarkozy once boasted that his favourite film was Saving Private Ryan, today he can discourse at length on the Danish classic film director Carl Theodor Dreyer or the German Ernst Lubitsch.

Last month, according to Liberation newspaper, Mr Sarkozy hosted a dinner at the Elysee for four actors who had each played the part of a French president on stage or screen (including Denis Podalydes as Sarkozy).

We learn that there followed a conversation about theatre, film and literature, which left the actor Michel Vuillermoz (de Gaulle) "seduced".

"I found (Sarkozy) courteous, elegant and curious," he was quoted as saying.

For Franz-Oliver Giesbert, "Today (the president) no longer looks like a lost child… when the conversation turns to the arts."

A number of questions spring to mind when contemplating this transformation. First of all, how deep does it go?

The Comedie-Francaise might not be everybody's cup of tea

It is well-known that Sarkozy has an extraordinarily retentive mind as well as a capacity for obsession.

Could it be that he has simply swotted his way to sophistication in a bid to please his wife?

That is certainly the view of Jerome Garcin, presenter of the arts programme Le Masque et la Plume (The Mask and the Quill) on France-Inter radio.

"I am very doubtful," he said. "When it comes to culture, I do not believe in that kind of metamorphosis. You can't suddenly switch from Spielberg to Dreyer and be sincere about it."

The writer Yann Moix is marginally more indulgent. "Carla definitely pushed him at the start, but then she took the stabilisers off the bike, and now I think Sarkozy is quite happy pedalling by himself."

Another question concerns the politics of it all.

If Mr Sarkozy is rebranding himself as an aesthete ahead of next year's presidential election, is that necessarily a wise move? After all, the president's whole career has been built around rejection of the Paris elite, and as a policy it has served him pretty well.

Most voters would share his apparent boredom in the Comedie-Francaise, and they will not have even heard of Carl Theodor Dreyer. As for the crude comic and Papal buddy Jean-Marie Bigard, he is well-liked by the masses and actually quite funny.

Perhaps by aping the language of the Left Bank salons, Mr Sarkozy risks both the derision of those he aspires to and the contempt of those he leaves behind.

But there is a deeper, psychological aspect to this story, which Mr Giesbert - no fan of the president - grasps at in his biography.

In the last chapter of Monsieur le President, Giesbert describes a lunch at the Elysee in February this year.

The journalist finds himself utterly bewildered by the extent of Sarkozy's learning. The conversation starts with literature, as the president sings the praises of the late anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss.

They move through the French classics before coming to modern American books - a speciality of Mr Giesbert, who is surprised when President Sarkozy corrects his memory of Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath.

They discuss Albert Camus, and the president tells how on a recent trip to Algeria he made a detour to the town of Tipasa because it was the scene of Camus' 1938 book Nuptials.

"When the journalists asked me why, I said 'If you don't understand that's your problem'," Mr Sarkozy said.

Mr Giesbert feels utterly nonplussed.

"I have known Nicolas Sarkozy for 25 years, and never once have I had a glimpse of this side of his personal universe. If he'd just crammed a few books in the preceding days, I would have seen through him.

"If his knowledge is recent, which I cannot help but suspect, then he has already read an awful lot.

"But I owe it to the truth to say that contrary to the legend that I myself have fostered, the president is anything but uncultured."

Mr Sarkozy, Franz-Oliver Giesbert concludes, has indeed changed.

"He is no longer exactly the same man. Perhaps finally he has started to discover who he really is."