On the trail of George Orwell’s outcasts

- Published

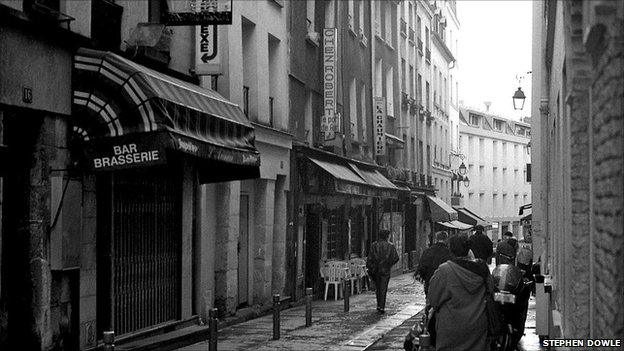

Orwell's narration begins in the street he called the Rue du Coq d'Or, in the 5th Arrondissement, where he once lived

Some 80 years after George Orwell chronicled the lives of the hard-up and destitute in his book Down and Out in Paris and London, what has changed? Retracing the writer's footsteps, Emma Jane Kirby finds the hallmarks of poverty identified by Orwell - addiction, exhaustion and, often, a quiet dignity - are as apparent now as they were then.

"Quarrels, and the desolate cries of street hawkers, and the shouts of children chasing-orange-peel over the cobbles, and at night loud singing and the sour reek of the refuse carts, made up the atmosphere of the street…. Poverty is what I'm writing about and I had my first contact with poverty in this slum."

Such was George Orwell's recollection of what he called the Rue du Coq d'Or in Paris, 1929 - the real-life Rue du Pot de Fer. Today it's pleasure rather than poverty that defines the Latin Quarter that Orwell frequented 80-odd years ago. The chic pavement cafes are full of contented-looking people leisurely sipping their vin rose, and the air is perfumed by the sweet smell of crepes and tourists' money.

But poverty hasn't left Paris - she's simply changed address. She may not look quite the same as she did in the 1920s but if Orwell were to meet her again on these streets, he'd know her straight away. And I doubt he'd find her greatly changed...

Poverty came knocking on Claudine's door five years ago when she was made redundant. She leans in close to me as she talks, her right hand often rising to her mouth as if it wants to censor the words that her lips keep forming. "Tomber dans la misere" (falling into misery), is the phrase she whispers most and I notice her breath is sour like someone who diets or skips meals.

"We don't eat lunch," she tells me. "It's just my little way of economising." She nods down to her bulging shopping caddy. "It's enough for my family's dinner," she says, "but not enough for two meals a day."

Shame

Claudine and I are sitting in a big warehouse in the north of Paris, which serves as a food distribution centre for the city's chronically poor. It reminds me of the sort of indoor market you find in the less salubrious quarters of former Soviet states - mountains of unbranded pasta and rice piled on tables, misshapen, anaemic-looking vegetables wilting in crates, biscuits and chocolate wrapped in such bland, stark white paper, that not even a child could be excited by its contents.

Download the tablet version

On the trail of Orwell's outcasts[186 KB]

Most computers will open PDF documents automatically, but you may need Adobe Reader

We watch the steady line of people, Europeans, Maghrebians and West Africans, methodically trudging from table to table, collecting their rations and stuffing them quickly into a pram hood or caddy. Despite the animated cheerfulness of the staff, I notice not one of the customers meets their eye as they take the food parcels.

Shame, Claudine - who is French - tells me, is what links everyone here. She's told no-one that her weekly shop is a hand-out and she doubts anyone else here has admitted it either.

The secrecy that's attached to poverty is one of the first things that struck Orwell.

"From the start," he wrote, "it tangles you in a net of lies and even with the lies you can hardly manage it."

Milly is fighting poverty with a fierce, indignant energy. A bilingual secretary from Cameroon, she is immaculately dressed and has the practised deportment of a society debutante.

In the drop-in centre where I meet her, she looks decidedly out of place next to the dusty, weary figures that are slumped beside her. Appearances, she tells me, are everything if one is to cling on to one's dignity. She agrees to talk to me but only in a private room so that the other people here won't realise that her situation is as bad as theirs. When the door closes she tells me that she's homeless and last night she slept on a veranda.

Milly is facing deportation. She came here legally but after she fell ill and had to stop working, her carte de sejour - the papers that allow her to stay and work in France - were revoked. She admits that she is homesick but is terrified to return to Cameroon empty-handed. I ask her if her family know she's homeless and she throws her hands up in the air and rolls her eyes in horror.

"It would kill them," she tells me. "They would drop down dead with shame."

Aching all over

When I meet Modi from Mali, he looks as if he might drop down dead with fatigue. Like Orwell, Modi is a plongeur, a washer-upper in a big restaurant and he works six days a week, 12 hours a day cleaning pots and pans.

When we talk in the bar of a neighbouring restaurant, his head keeps drooping onto his folded arms and it seems to be such an effort for him to articulate his words that he either slurs them all together in a gluey, glottal jumble, or shoots out small phrases in tiny bursts of energy that fizzle out before the last word has been formed.

Orwell complained that when working as a plongeur he felt as if his back were broken and his head "filled with hot cinders". Modi agrees that he aches all over and at the end of the day he cannot feel his feet.

Because rent in Paris is too expensive, he lives an hour's train ride outside the city. Although after midnight the trains are slower so it takes two hours for Modi to get home. He gets up at 0700 and gets to bed at 0200. Most plongeurs in Paris these days are either Pakistani or West African. I stop asking myself why that is, when Modi tells me how much he is paid - just under 4 euros (£3.50) an hour. He's working, of course, "on the black".

"The last time I had a night out," he says flicking through a virtual diary in his brain, "was... last year."

Madame Jolivet can have as many nights out with friends as she wants to - her problem is she's not allowed to have any nights in with them.

Madame Jolivet's tiny B&B room costs 1,730 euros a month

The rules of her B&B state clearly that visitors are not permitted, but I have managed to frighten the landlady into admitting me by pretending to be an official from the local authority. Now I'm standing (albeit slightly stooped) in her fusty-smelling attic apartment.

I am Madame Jolivet's first visitor in six years and she is laughing hysterically at having won this tiny victory over her hated landlady. I tell her that in Orwell's day, the residents in his filthy hotel used to yell "Vache! Salope!" ("Cow! Bitch!") at their landlady, and Madame Jolivet doubles up with mirth as she mimes the insults at the sky-light. Then, quite suddenly, she looks sick with fear and switches the TV on at a high volume, motioning to the door and telling me the landlady is probably listening at it. She's right. We hear her tread softly back down the stairs.

Orwell's hotel room was infested with bugs - Madame Jolivet's is infested with mice. She's tormented by their scratching at night. She's caught them on camera during the day, and once she found one in her fridge. She complained to the landlady who warned her that if she mentions it again, she'll kick her out - after all, she's already been warned that her daughter's voice is too loud.

Madame Jolivet is a large lady and she squeezes herself round the tiny space of her apartment. When she's at the sink she's jammed between the bed and the table, her body painfully curved sideways to avoid smacking her head on the sloped ceiling. The landlady charges 1,730 euros (£1,500) a month for this space which she rents out as a 16 sq m apartment. Recently the police did a spot check on Madame Jolivet's apartment and recorded the actual habitable surface area as just 5 sq m - that's the size of about six or seven beach towels.

Madame Jolivet lives here with her grown-up son and daughter. Until last year her other daughter lived with them, too, but she tried to kill herself twice and is now in psychiatric care.

Although it's miles from the hostel where she's staying tonight, Milly, the dignified lady from Cameroon offers to come with me in the taxi to the Gare du Nord where I'm catching my train home to London to make my next step of Orwell's journey.

"In my country," she smiles, "we never let a traveller start a journey alone."

She's very jolly in the cab, reminiscing about her family, her sister in London, the present she sent her nephew in America last year. By the time we get to the Eurostar terminal I've completely forgotten that Milly's homeless and I realise with a real physical shock that this is exactly what she wanted, that she wanted me to see her as she was before poverty possessed her - a very proper, very animated, valuable woman.

She waves me off, her whole body swaying into the gesture, in that exaggerated way that small children say goodbye. Each time I turn, she's still there, both arms in the air, her head following the rhythm.

Sitting in my seat on the train, my eyes closed, I can see her still. The last line from a Stevie Smith poem comes into my head:

Not Waving but Drowning...

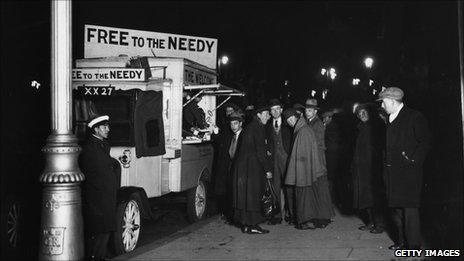

Orwell closely studied the tramps of London

"There exists in our minds," wrote Orwell, "a sort of ideal or typical tramp - a repulsive, rather dangerous creature, who would die rather than work or wash, and wants nothing but to beg, drink and rob hen-houses... I am not saying, of course, that most tramps are ideal characters; I am only saying that they are ordinary human beings, and that if they are worse than other people it is the result and not the cause of their way of life."

Five minutes inside the soup-kitchen in Hackney, east London, and I immediately understand what Orwell meant - that the "typical tramp" does not exist.

The "service-users" - as the volunteers here call them - are a truly disparate group - some look as if they've just stepped off the tube after a busy day at work, others are unkempt and smell feral. Some are evidently fighting a losing battle with drugs and alcohol, while others look more in keeping with an old folks' home.

A well-spoken woman who is far more elegantly dressed than I am, and whom I take to be a doctor, confides in me her concerns about the well-being of a schizophrenic service-user she recently escorted to hospital. She then confounds me by sitting down to eat the free meal. A man with a carefully oiled black quiff is introduced to me by a grinning volunteer as Shakin' Stevens. I smile conspiratorially with him at Shaky's delusions and am later told by the service manager that the volunteer, himself, is delusional and has been coming here to eat each week for years.

Today's 'down and outs' are known as 'service-users'

Misfits

What was it that Orwell said? "Change places and handy dandy, which is the justice, which is the thief?"

I am instantly struck by the civility of the meal time. A tattooed and very inebriated punk knocks over an elderly lady's walking frame as he staggers to find a free seat. He apologises, asks if the seat beside her is taken and then appears to engage her in polite conversation. When he is served a plate of Mediterranean vegetable pasta by the charming French chef, he thanks her profusely and leaning towards the Polish man opposite him asks if he would kindly pass the salt?

As I pour tea and coffee, an emaciated black man in a filthy sweatshirt shakes my hand warmly and asks me how I'm doing today? Society's misfits, fitting in.

It's here I meet Stuart, who is currently on a methadone programme and who has serious mental health problems. Physically abused by his father, Stuart was put into care in the North East of England, where he claims he was then systematically sexually abused until he gathered the courage to run away to London at the age of 15.

Aside from a brief respite of a year or two when he had a council flat, the London streets have been the only home he's known. He is now 40. I ask him to tell me what he remembers about those early years sleeping rough.

He doesn't miss a beat before replying, "Crack, heroin, begging, robbing, stealing and mugging". An entire life, reduced into just six words.

Grant on the other hand can talk the hind legs off a donkey but he prefers to steer clear of personal details, claiming there are many people worse off than him.

He zooms through his life story with a dismissive wave of his hand - adopted, never held down a relationship, used to work in social care, lost his job, lives in a hostel, spent a long time in hospital after being brutally attacked on the street.

Orwell did the rounds of the night shelters and soup kitchens of London

He leaves out the part about his fairly evident problems with alcohol and when, three weeks into our acquaintance, I ask him about that side of his life he snarls defensively, "So that's what you think is it? I'm just yet another homeless drunk?"

Grant is articulate and funny. He's wary and prickly, yet sensitive and compassionate.

He likes Orwell but prefers Jack London. When my questions become woolly, he pulls me up for being unfocused and he is constantly re-assessing and re-evaluating his own beliefs and opinions. Twice after our meetings he has sent me text messages, apologising for sounding grumpy. When we talk late in the evening, he suddenly checks his watch and becomes concerned about how I'm going to get home to the other side of London. When I ask what keeps him going in life, he gestures towards the volunteers who are clearing up the kitchen.

"Belief in your fellow man's goodness," he says. "Because by and large people are good, aren't they?"

Recession

Orwell always defended tramps' reputation as "drunks", pointing out that none of the tramps he knew had any money with which to buy beer. But today alcohol is cheap and features heavily in the lives of many of those on the streets. Not least in the lives of the many Poles who came to seek their fortunes as labourers in the UK when the borders opened in 2004.

When the recession bit and the building sites closed, they had limited access to benefits and quickly found themselves homeless. The volunteers in many of the drop-in centres and soup kitchens I visit in London tell me that around a good third or even half of their service-users are now Polish. As one careworker put it, they're "Orwell's latter-day Irish tramp" - Catholic, slightly on the fringe of the London homeless community, and plagued with a "great thirst".

Zibbi, who's in his early 40s came to the UK seven years ago, where he got work in a salad factory in Peterborough. For nine months life was "good-good", he tells me in his broken English.

"Good-good, because Zibbi is good and Zibbi no drink."

Zibbi refers to himself almost entirely in the third person, as if while talking to me, he has stepped outside of himself and has become a detached observer, albeit with an anthropological curiosity in his own behaviour.

"Do Zibbi drink today?" he asks me.

By the look - and smell of Zibbi - he does little else but drink these days. His face has bloated and taken on the colour of ripe plums, his hands shake and the sharp stench of pure alcohol from his breath overpowers even the acrid, vinegary smell of his clothes and the odour of hot grease from his recent fried breakfast, which still hangs in fat little globules in his beard and moustache.

He shakes his head. "Oh, lady," he says, "Zibbi drink not a little drink, Zibbi drink and drink. He drink vodka til…" (he makes a gesture of passing out). "Until bang and bye bye. Game over."

Zibbi blames the heavy drinking culture of his country for his weakness and claims his cousin, Miro, is the worst influence on him, egging him on to have just one more. Frequently he seems to set himself on stage, theatrically acting out imagined dialogue he has with Miro and with his disgusted family. It's like watching a medieval morality play, with the forces of Good and Evil battling for power.

The drop-in centre has set Zibbi up with an alcohol adviser who is trying to help him cut down his alcohol consumption. He talks about her in hallowed terms, and when he whispers her name "Karen", he lifts his hands and face to heaven. I suspect she's the only woman he has regular contact with. When I meet Karen later she tells me that she's trying to wean Zibbi off calling her "Mummy".

I ask Zibbi what he thinks of himself and he looks startled. "Me? Zibbi?" he asks uncertainly and his eyes become confused as if he's struggling to connect the alcoholic Zibbi character with the man who speaks his words.

"I… I… I don't know," he stutters. He hangs his head and slumps in his chair.

"So tired lady. I… I…"

'Not needed'

Zibbi becomes distressed as he fruitlessly searches for words which might join his isolated personal pronoun and we stop the interview. I realise he has totally lost his sense of self.

A few miles east in Hackney, and Mikael, a young, good-looking Pole in his late 20s, has also lost his identity - or at least his identity papers. Someone stole them one night a few months back when he'd blacked out in a vodka-induced stupor. Mikael is so softly spoken that he's barely audible at times. He tells me that talking to me is like going to Confession.

"I've thought about it [my situation] so many times on the streets," he says. "Especially when I'm alone, but no-one really asked me before... I feel strengthless and hopeless."

Mikael underestimates himself. A bright man and a fluent English speaker, he's enrolled in an Alcoholics Anonymous programme and, in a bid to stay on track, has made the very difficult decision to eschew the company of his fellow Poles and all other rough sleepers. He is still on the streets but unlike Zibbi, he is wearing freshly laundered clothes and looks fit and fairly healthy. He may not smell of alcohol but he reeks of loneliness.

Seven years ago, life was very different for Mikael. He had a legal, well-paid job as a labourer, he had a fiancee, a studio-flat and a gym membership. There were holidays, cinema trips, football matches - there was, as Mikael puts, it a time when he was "really connected to society… and there was a future". Then his boss sold his business and moved overseas. Mikael began drinking heavily, lost his studio and his girlfriend. I ask him what he misses most about his old life, fully expecting him to say the obvious things - a hot shower, a comfortable bed, his own food. But Mikael says something quite different.

"I feel like I'm not needed by this world. Like nobody needs me," he says quietly. "I miss my girlfriend because I felt then someone needed me. And I felt needed in terms of work."

The evil of poverty, wrote Orwell, is not so much that it makes a man suffer as that it rots him physically and spiritually. Work, he insisted, is the only thing to turn a half-alive vagrant into a self-respecting human being.

Mikael is desperate to find a job believing that work is the yellow brick road which will lead him "to come back to the normal life," as he puts it. Although he admits that it's hard to keep motivated when you wake up cold, wet and shattered from a disturbed night in a shop doorway.

Mikael's progress is sporadic. He has long spells when he's free of alcohol and then sudden lapses which infuriate him and provoke tirades of self hatred, especially when he imagines what his family back home in Poland would say if they knew he was on the streets.

I return to the soup kitchen three weeks later confident of meeting Mikael again but worryingly, he doesn't turn up. I think of the boyish shyness which passed across his face when he had told me that sometimes when he was very lonely he talked to God. The prayer he recited was always the same:

"Hello God - I hope you still remember me and keep some faith in me."

At the end of Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell asks himself what he's learnt from his experiences on the streets and in deference to the great man I shall ask myself the same question. I have learnt how quickly the dry rot of poverty stultifies and festers, crumbling confidence and destroying dignity.

I have seen how poverty marginalises, separates and ridicules. And I have understood that the chief cruelty of homelessness is that it doesn't dull the sensibilities of the man sleeping in the doorway but rather spitefully heightens them, forcing upon him so many cavernous hours in which he can burn with shame, ache with loneliness and cry for his mother.

Perhaps Mikael sums it up for everyone I have met both in Paris and London when he says, "You know it's so easy to lose everything. But it's so, so tough to get it back."