Greek economic crisis: Timeless values help villagers

- Published

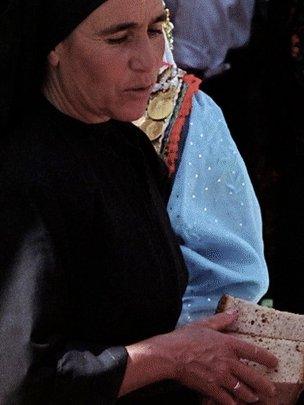

Older villagers are used to a frugal existence

Roger Jinkinson, a British writer who lives in a remote village on the Greek island of Karpathos, reflects on how the profound economic crisis is affecting his small rural community more than 400km from Athens.

Although times are hard, he believes that a long tradition of thriftiness, a thriving barter economy and the return of young people to work on the land will help the village weather the crisis.

The older generation in the village are thrifty and hard working; they are used to a frugal existence and times of extreme hardship.

Hundreds of thousands of Greeks died of starvation and the complications of severe malnutrition during World War Two and the Civil War that followed.

Memories of those times can be seen etched in the faces of the old people and the habits handed down to their children.

Women are in charge of the home, a loaf of bread is kept until it is used and, if you could see the effort it takes to produce, you would understand why.

Hand-sowing wheat and barley, reaping, winnowing and grinding the grain is back-breaking work, and kneading dough for the huge loaves baked in outside wood ovens is not light work either, so it is easy to sympathise with the women as they carefully store a week-old loaf back in its bag.

In Britain we throw away millions of tonnes of food a year. In the village they throw away nothing.

Dwindling incomes

This is a small, isolated community on the edge of an often wild and turbulent sea.

Local women make cheese, some of which can last for up to two years

There are three main sources of income: crofting from the sea and the land, tourism, and money from the diaspora.

The last two have suffered adversely from the crisis in Western capitalism.

Tourism is in decline due to higher travel costs and the shortage of money in northern Europe.

The decline has been exacerbated by the trend away from small village hotels and tavernas towards all-inclusive holidays at globally-owned and funded mega-hotels.

International currency fluctuations also have an adverse impact.

Many of the older men in the village went to work in the US and Canada, where they paid their taxes and social security dues before returning to retire in Greece.

The US and Canadian governments keep their part of the contract and dutifully pay pensions into the local bank accounts of the returned workers.

But, despite all the furore and turmoil, the euro remains strong against the dollar - added to which inflation has eroded the value of these small pensions.

While bankers continue to make billions from playing the market, these retired builders and decorators, taxi drivers and cooks, lose 10% just to change their money from dollars to euros.

Wages in the village remain low. Plasterers and bricklayers earn 40 euros a day - if work is available. The few government jobs pay even less and, in this context, it is understandable that workers in Greece do not rush to pay their taxes, particularly when they see the ostentatious wealth of the upper decile.

Produce shared

Greek society is family-based, the public sector is over-bureaucratic and its economy unreformed.

Produce is shared in times of plenty

Next to the state, the Greek Orthodox Church is the largest land owner in Greece.

It has substantial holdings in Greek banks, many of its employees are funded by the state, and yet it pays very low taxes.

In less than 50 years, Athens has grown from the size of a small provincial town to an urban sprawl of five million, sucking the brightest and best from the rural community and unbalancing the economy.

Much of the trade in the village is done by barter and the villagers care little for the EU, the World Bank and the IMF.

Excess produce is shared in times of plenty. When times are hard, the proud people stay in their houses and go to bed early.

Among the old men in the local cafe there is a near unanimous view that it was a mistake to enter the eurozone, and a longing for a return to the drachma, which they believe was the world's longest running currency.

While they get by on very little, the dreams of their children and grandchildren are being destroyed.

Community ties

Local traditions have been strengthened as young people return

The only positive outcome of the crisis is the return of young people, including graduates, to the village.

There are plenty of empty houses here, no shortage of land, and good rains last winter have expanded the opportunities for new crops, as well as giving greater returns from old.

An attraction is that work on the land is mainly a winter activity, leaving the summer months free for fishing and beach parties.

The return of the young is revitalising the village, strengthening family and community ties and reversing a century-long trend of depopulation.

This is a village with strong traditions.

The young people will learn much from their parents and grandparents, and bread will be kept to the last slice.

Roger Jinkinson is the author of Tales from a Greek Island, external