Chirac-Villepin allegations revive sleazy memories

- Published

Robert Bourgi has dropped a bombshell

The French are torn between revulsion and disbelief over claims that ex-President Jacques Chirac and his ally Dominique de Villepin received tens of millions of dollars in bundles of banknotes from several African leaders.

The allegations are made in an extraordinary newspaper interview with the man who, for many years, acted as an unofficial intermediary between the Elysee palace and African governments.

Robert Bourgi, a 66-year-old lawyer, claims in Le Journal du Dimanche that in Mr Chirac's 2002 re-election campaign he personally passed on cash contributions worth millions of dollars.

The money allegedly came from the leaders of five African countries, all former French colonies: Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon. Later, the president of the former Spanish colony of Equitorial Guinea also allegedly made payments.

Mr Bourgi claims that Mr de Villepin - who was Mr Chirac's cabinet secretary, then foreign minister, interior minister and prime minister - personally handled most of the cash deliveries, which, he says, lasted from 1997 till 2005.

Networks of influence

In some bizarre touches of apparent detail, he relates how on one occasion the money arrived at the Elysee palace hidden in African bongo drums. On another occasion, the notes were wrapped up in a poster for a Mini Cooper car.

Mr Chirac and Mr de Villepin have furiously denied the accusations, and promised to sue for libel.

However, if they are true, the allegations are explosive. They could show that the networks of corruption and influence linking France and its former colonies in Africa lasted much longer than previously acknowledged.

They would destroy the reputations of both Mr Chirac and Mr de Villepin, both of whom quite separately have already faced criminal charges relating to misuse of their positions.

Mr Chirac is currently on trial on charges of siphoning off public money to pay for his political party in the early 1990s.

Mr de Villepin has been accused in the Clearstream affair of conspiring to smear his arch-enemy President Nicolas Sarkozy, in a dirty tricks campaign.

He was acquitted of those charges, though an appeal, submitted by the prosecutor, is due to be decided this week.

Finally, the allegations, if verified, would also blow apart the claim that French politics has cleaned itself up since the big scandals of the 1990s.

Public funding of political parties was supposed to have put an end to the prevailing sleaze.

But doubts persist, as recent claims about the L'Oreal heiress Liliane Bettencourt and her relations with Mr Sarkozy's UMP party show.

Undeclared war

Mr de Villepin sees the interview as a deliberate attempt to scupper his chances in next April's presidential election.

Dominique de Villepin and Nicolas Sarkozy have long been bitter rivals

He and President Sarkozy continue to detest each other, and from the de Villepin perspective the "revelations" are seen as a new attack in their undeclared war.

In his interview, Mr Bourgi is particularly virulent towards Mr de Villepin - whose "moralising" tone he says he can no longer abide.

On the other hand, he is sparing towards Mr Sarkozy, who he says agreed to keep him on as an Africa adviser - but only on condition that the secret payments cease.

However, some have cast doubt on Mr Bourgi's exoneration of the current president.

Jean-Francois Probst, a close ally of ex-President Chirac, told the AFP news agency it was "simply not credible" to claim that the payments stopped with Mr Sarkozy.

He said that Mr Bourgi networked with African leaders ahead of the 2007 presidential election and brought back one million CFA francs, external for Mr Sarkozy's campaign. This is denied by the Elysee.

'Getting dangerous'

Some of the apparent detail in Mr Bourgi's newspaper interview is mind-boggling.

He says he was first approached by Mr Chirac and Mr de Villepin in 1997, after the funeral of Mr Bourgi's mentor, Jacques Foccart.

Foccart was a legendary figure in what is known as la Francafrique, external - the relationship maintained by France with its former colonies - and for 30 years presided over a web of personal, political and financial relations between them and the Gaullist party.

Under the original arrangement, the African leaders guaranteed French access to mineral resources and arms contracts, and helped France maintain its standing on the continent. In return a French military presence more or less ensured their survival in power.

In later years the mutual financial interests grew in importance. Major state enterprises in France like the oil giant Total paid out millions in bribes. The quid pro quo was often that African leaders syphon part of their gains back to France to fund political parties.

According to his account, Mr Bourgi was summoned by Mr de Villepin to the Elysee, where Mr Chirac asked him to "take on what we used to do with Foccart".

Mr Bourgi says he then introduced Mr de Villepin to several African leaders. Initially they were suspicious of Mr de Villepin, but soon the payments started to flow.

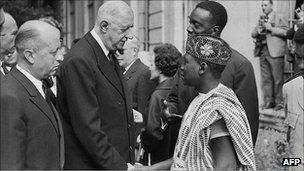

Jacques Foccart (left) was pointman on Africa to a series of French presidents

"When there were big deliveries to be made, I was expected [at the Elysee] like Father Christmas. In general there would be a dinner organised by Jacques Chirac for the donor, and then the delivery would take place in [Mr de Villepin's) office," he says.

"Once I was late… I had a big sports bag full of money and it was so heavy my back hurt. Chirac and [the late Gabonese leader Omar] Bongo were sitting together comfortably in de Villepin's office.

"I greeted them and then put the bag behind the sofa. Everyone knew what was in it."

He recounted details of how money was delivered to Mr de Villepin. "Sometimes Dominique took out the money in front of us... He'd coolly arrange the bundles of notes in the drawers of his desk," says Mr Bourgi.

According to Mr Bourgi, the payments ended in 2005 when Mr de Villepin said it was getting too dangerous.

"I remember de Villepin said to me: 'If a judge starts asking you questions... it's going to end badly,'" he says.

Amid widespread shock over the allegations, there have been calls for a police investigation as well as a parliamentary commission of inquiry.

Herve Morin, leader of the New Centre party, said the claims were going to cause "huge political damage".

However, some have urged caution, warning that Mr Bourgi may have motives of his own for fingering his former collaborators.

He himself says he gave the interview because: "I am a penitent. I am beating my breast in shame. I have seen too many indecent things, and I want France to be clean."

However, Le Monde newspaper said that after four years working unofficially for Mr Sarkozy, Mr Bourgi has recently gone out of favour.

Alain Juppe, who took over as foreign minister at the start of the year, has a particular enmity towards the man and insisted he be sidelined.

- Published4 September 2011

- Published3 September 2011

- Published20 May 2011

- Published15 December 2011