Magnitsky death: Falling ill in a Russian jail

- Published

The newly refurbished Butyrka gives prisoners more cell space

The ongoing dispute over the death in custody of Russian corporate lawyer Sergei Magnitsky has drawn attention to the Moscow remand prison where he was being held.

The gates of Butyrka, one of Russia's oldest prisons, could well be in a museum. Made of oak and hand-wrought steel, they were installed when the prison was built 240 years ago.

Colonel Sergei Telyatnikov, the prison's director, says it is time for the old gates to go, but he is fond of the metal.

"The original stuff," he says. "When we do repairs to doors and grills we discover it's much better than the modern steel."

Butyrka sees a lot of repairs these days. Possibly because, since Magnitsky's death, the prison has been attracting the attention of human rights activists around the world.

Mr Telyatnikov himself is the replacement for a previous Butyrka director, who was removed after Magnitsky's death.

Prison make-over

Magnitsky died in November 2009, after spending four months in some of the prison's oldest and grimiest cells, as he faced trial for tax fraud.

His diaries describe rooms full of rats and sewage, badly ventilated and poorly heated. Despite falling ill he was not given adequate medical help.

An independent investigation by the Public Oversight Commission concluded the conditions of his arrest and denial of medical help had been a form of torture, designed to press Magnitsky to withdraw accusations of corruption against police officials involved in an alleged multi-million tax rebate scam.

Sergei Magnitsky died in 2009

The type of cell used by Magnitsky has disappeared. In 2010, after extensive renovation, all such cells were turned into places of solitary confinement.

The mint-coloured walls are spotless. Two layers of bars on the windows are reflected in shiny floors. There is a modern toilet. The plumbing, Col Telyatnikov hastens to add, is in perfect shape.

The cell itself, once shared by up to three people, is now designed for one inmate only, thus surpassing meagre space limits set by Russian law.

Col Telyatnikov looks tired of questions connected to Magnitsky's case. In this year alone I am, he says, probably the 100th journalist to see these cells and ask these questions.

According to the prison director, all repairs were planned long in advance and have little to do with the critical report submitted by the activists.

It is hard to verify this as well as the director's assertion that the same high standard now applies to every cell in the prison.

I was not given a chance to talk to the inmates, most of whom are on remand or awaiting trial. Two men in another cell I visit are ordered to remain silent and turn their backs to the camera, unable to tell me whether their conditions are, indeed, regular.

Confined in wheelchair

In August, two of the prison medics who treated Magnitsky in Butyrka were charged with negligence.

Col Telyatnikov says there is a list of ailments which qualify for prison release and any sufferer is assessed accordingly.

Try telling this to Sergei Kalinin. A top manager in one of Moscow's banks, he was jailed in 2007 accused of fraud, later returning to Butyrka during a second trial.

By then he already had problems walking after an earlier car accident. Moving between prisons made it worse.

"From the start medical assistance was tied to my testimony," Mr Kalinin says.

"If I provided what the investigators needed I would be allowed to remain in a proper prison hospital."

He refused to co-operate and was returned to Butyrka, which has only a limited medical facility. By 2009 he had lost control of both of his legs.

For two years he could not use a shower and his movements in a wheelchair were severely restricted by the prison's outdated design.

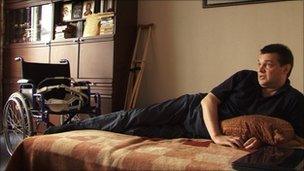

Sergei Kalinin remains disabled after his release from prison

In theory, the disability could have provided him with a release from prison, but all petitions submitted by Mr Kalinin's defence were turned away. Finally, in 2010, the court heard his appeal but decided against release.

According to Mr Kalinin, the verdict was based on an affidavit signed by Butyrka's doctors and Col Telyatnikov. It stated that Mr Kalinin had declined an offer of an official assessment of his disability.

He protests that he never refused such an assessment.

"It's funny in a sad sort of way," he says. "No matter what kind of illness you have, no matter how grave, if someone out there decides you need to stay locked up, you will be."

He was convicted in a second trial but finally released on medical grounds in early 2011, a year before his sentence ran out.

Col Telyatnikov refused to comment, saying all questions should be addressed to the court which heard Mr Kalinin's case.

Closure call

Human rights activists say the new prison authorities allow them access to inmates with medical problems but help for ailing inmates is limited.

Last month the Public Oversight Commission called for Butyrka to be closed altogether and a new, modern prison to be built instead.

Sergei Sorokin, a Commission member who recently visited the prison, says this alone may not help eradicate the issue of prison abuse and misuse of law.

Courts in Russia, he argues, are very reluctant to apply existing rules allowing release on medical grounds.

He blames corrupt police and officials who use the threat of imprisonment to extort money or illegally seize assets from accused businessmen.

According to Sergei Kalinin, only real independence for doctors working in prisons will improve the plight of inmates who fall ill.

- Published12 August 2011

- Published10 November 2010