No end in sight to Russia's era of Vladimir Putin

- Published

- comments

Vladimir Putin has built a system that disables any political opponent

It feels like the day after a general election.

Russians now know the name of their next president - Vladimir Putin.

They know who their prime minister is going to be - Dmitry Medvedev.

They have a pretty good idea which political party will have the majority in parliament - United Russia.

They know all this, even though parliamentary elections are still two-and-a-half months away. And the next presidential election will not be until March 2012.

The results are already clear. When Dmitry Medvedev took the stage at a party conference on Saturday and backed Vladimir Putin for president, he effectively handed back the keys to the Kremlin. Job done.

The presidential election will be little more than a referendum on what has already been agreed behind closed doors - that Mr Putin will return to the presidency.

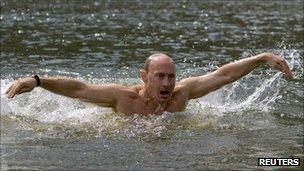

Strongman image

It is unthinkable that Vladimir Putin could lose that election. He remains the most popular politician in Russia.

That is partly because of his strongman image, that goes down well with the public.

And it is partly because the political system he has created prevents any potential rivals from appearing on the scene, from getting air time on national TV, and from gaining authority.

It is the same with Russia's political parties. In December's Duma election, only those parties approved or tolerated by the Kremlin will have the opportunity to contest the poll.

Experience shows that opposition parties viewed by the authorities as anti-Kremlin or anti-Putin, and which openly criticise the Russian prime minister, normally struggle to receive official registration.

So, what do Russians make of this pre-ordained transfer of power?

Judging from some of Monday's Russian papers, there is a degree of anger.

The popular tabloid Moskovsky Komsomolets has a cartoon on its front page. It shows a ballot box with a heart-shaped slot for the ballot papers. It is a sign that, in Russia, elections have become little more than a plebiscite on the nation's love of one man.

The paper accuses Vladimir Putin of wanting more than just 12 more years - two terms - in power.

"You seek eternal power," it says. "You're counting on medical progress. You hope to buy yourself eternal life. Then the questions of elections and successors will flake away naturally like crumbling plaster."

According to the broadsheet Vedomosti, Saturday's announcement shows that Dmitry Medvedev's time in the Kremlin was merely "camouflage" for a third Putin presidential term. It likens Russia to the Titanic, heading for a disaster.

Vladimir Putin's strongman image seems to go down well with many Russians

Some of President Medvedev's own advisers are deflated, too.

Last week Medvedev adviser Igor Yurgens told me he was sure that the president would seek a second term. Today he admitted defeat.

"I feel disappointment bordering on anger," Mr Yurgens told me at his Modernisation think-tank in Moscow. "Their smiling announcement that they already had it in their heads for a long time was humiliating. The rational explanation is that Medvedev was under pressure and the stronger and more influential Putin got the upper hand. "

On Saturday the Russian president's economic advisor Arkady Dvorkovich tweeted simply: "There's no cause for rejoicing."

But on the streets of Moscow, I found people less pessimistic.

"Putin has the experience, he's the best candidate for president," Vladimir told me. "I don't see anyone else who could do the job."

I asked Vladimir whether he would bother voting in the presidential election, now that the result seemed clear.

"Yes, I will vote," he replied. "It's my duty as a citizen."

Olga, too, will cast her ballot in March. "If nobody votes, then elections will cease to exist," she told me.

"From the point of view of democracy, it is not good that we have such a small choice. But at least we know Putin. He's been president before. I'm not against him."

- Published24 September 2011

- Published24 September 2011

- Published17 March 2024

- Published24 September 2011