Spain's Eta wounds will take time to heal

- Published

Police investigate a car bomb attack in Madrid in 2005

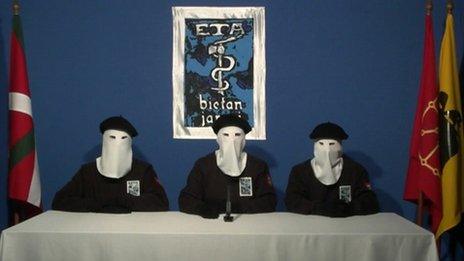

The video images were very familiar: Three Eta militants in white hoods topped with black Basque berets, surrounded by the symbols of radical separatism.

But this time, the message from behind the masks was substantially different.

Eta has announced what it calls the "definitive cessation of armed activities".

It was not a clearly spelled out surrender - the dissolution and unilateral disarming that Spain's politicians, including the government, have called for repeatedly in the past.

But just one hour after Eta's statement was released, Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero was addressing the nation on live television, hailing the triumph of democracy over terror.

"Today we are experiencing the legitimate satisfaction of the victory of democracy, law and reason," the prime minister said. "A satisfaction that is stained by the unforgettable memory of the pain caused by violence that should never have begun and must never return."

Spanish clampdown

Eta has killed 829 people in its fight for an independent Basque state, a long list of victims that includes police officers and politicians, journalists and judges - and ordinary citizens. It has bombed Madrid airport and a Barcelona supermarket; King Juan Carlos and a former prime minister have both been targeted.

In 1980 - Eta's bloodiest year - 92 people were killed.

But no-one has been killed on Spanish soil for more than two years. It is not the first lull, but this time the context is different.

Crucially, there has been a sharp clampdown by Spain's security forces. More than 700 Eta members are in prison, including several military chiefs. Close co-operation with French police means militants no longer find safe haven across the border.

But in tandem with that has come a strategic shift by the separatists.

In 2010, Izquierda Abertzale - the grouping of radical Basque separatists that includes Eta's political wing - announced that it would pursue Basque independence through purely democratic means. It has taken longer to get the militants onside.

"They know that Basque society cannot tolerate any more terrorism," Spain's Minister for the Presidency, Ramon Jauregui, told the BBC. "They've concluded that violence ruins their cause. It destroys it."

Residents reflect on the Eta ceasefire in the Basque city of San Sebastian

Since 1981, polls show "total rejection" of Eta in the Basque country rising from 23% to 64%.

The process reached its climax in recent weeks as Eta prisoners appealed to the militants to end the violence. On Monday, former UN secretary general Kofi Annan and others joined a self-styled peace conference in San Sebastian, adding international weight to the appeal.

Many figures from the Irish peace process, particularly Sinn Fein, have been heavily involved in Eta's slow unravelling; choreographing its exit to avoid admitting that 43 years of violence were in vain.

"Eta's statement is in response to the request from the international figures who've asked Eta to finish the violence, not the Spanish government," explains Basque newspaper editor Martxelo Otamanedi. "Eta will find it easier to finish if they ask," he says.

But some in Spain are struggling to accept what is happening.

No apologies

"Eta brags of its assassinations and summons the government to negotiate," shouts the headline of El Mundo daily broadsheet, angry at the militants' claim that its "struggle" - meaning its violent campaign - "created this opportunity" for peace.

An Eta attack at Madrid airport in 2006 killed two people

The statement makes no mention of Eta's victims and express no regret. Instead it pays tribute to those "comrades" who died fighting, or "are suffering in prison, or in exile".

"Eta says it's laying down its arms. But if the next government doesn't give them what they want they can go back to killing. It's what they've done for 50 years," argues Alfonso Sanchez, who still has shrapnel buried in his body from a 1985 bomb attack on his police minibus.

"They have to hand in their weapons, dissolve, and hand over their assassins to face justice. And they should ask pardon from their victims for all the harm they have caused," he says.

On the streets of Madrid this morning, many Spaniards remained cautious or plain suspicious of the latest developments.

"I don't trust them. So many dead, so many years - I don't trust any of this," Jose said.

"It's not the first time they've laid down their weapons then picked them up again. There's a lack of confidence here," Jose Antonio agreed.

But Carlos said he was moved. "I cried when I saw the news. There were a lot of attacks in my area of Madrid all my life. So I think this was a good day," he said.

Though cautious, through bitter experience, Spain's government has clearly decided the time is right to accept this move, and attempt to move towards a lasting peace.

Crucially, the man most likely to manage the process - Mariano Rajoy - agrees. The leader of the opposition Popular Party is set to win a general election in November by a landslide. He welcomed Eta's statement as "good news", but added that true peace of mind would only come with Eta's dissolution.

For his election rival though - Spain's former interior minister, who led the fight against Eta from 2006 - this is already an emotional moment. Alfredo Perez Rubalcaba has admitted that he "slept little, and cried a lot" last night. His only regret, he said, was that the violence did not end sooner.

"What we need now is reflection, time and unity," Mr Rubalcaba said. "And to remember the victims."

- Published20 October 2011

- Published20 October 2011

- Published17 October 2011

- Published16 May 2019

- Published8 April 2017