Charlie Hebdo and its place in French journalism

- Published

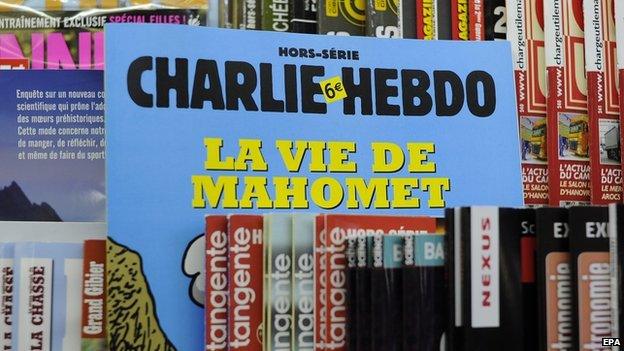

A special edition of Charlie Hebdo on sale on 2 January 2013

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has been attacked by gunmen, who have killed 12 people at its Paris offices.

It is the worst attack on a magazine which has been hit by violence before.

In 2006 many Muslims were angered by Charlie Hebdo's reprinting of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. They had originally appeared in a Danish daily, Jyllands-Posten.

The magazine's offices were fire-bombed in November 2011 when it published a cartoon of Muhammad under the title "Charia Hebdo".

One of the latest tweets on Charlie Hebdo's feed was a cartoon of the Islamic State militant group leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The editor, Stephane Charbonnier, had been under police protection, having received death threats. He and three other cartoonists were among those killed by the gunmen in the massacre on Wednesday.

Historical satire

France is on high alert after the deadly attack on Charlie Hebdo

The BBC's Hugh Schofield in Paris says Charlie Hebdo is part of a venerable tradition in French journalism going back to the scandal sheets that denounced Marie-Antoinette in the run-up to the French Revolution.

The tradition combines left-wing radicalism with a provocative scurrility that often borders on the obscene, he says.

Back in the 18th Century, the target was the royal family, and the rumour-mongers wrought havoc with tales - often illustrated - of sexual antics and corruption at the court at Versailles.

Nowadays there are new dragons to slay: politicians, the police, bankers and religion. Satire, rather than outright fabrication, is the weapon of choice.

But that same spirit of insolence that once took on the ancien regime - part ribaldry, part political self-promotion - is still very much on the scene.

Charlie Hebdo is a prime exponent. Its decision to mock the Prophet Muhammad is entirely consistent with its historic raison d'etre, our correspondent says.

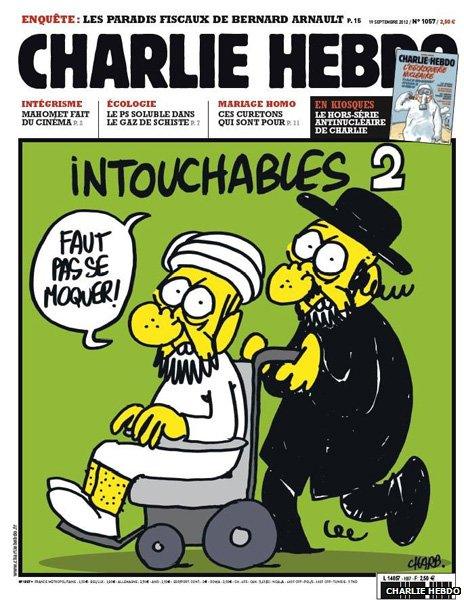

19 Sep 2012 issue: An Orthodox Jew pushes an old Muslim in a wheelchair, both shouting “You mustn’t make fun!”

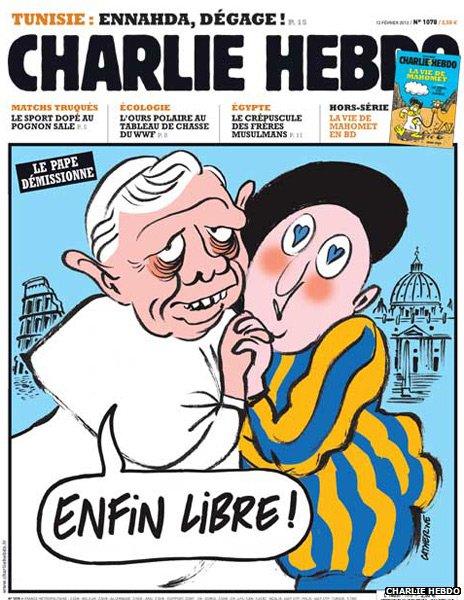

13 Feb 2013 issue: Pope Benedict, after resigning, kisses a love-struck Vatican Swiss guard crying “Free at last!”

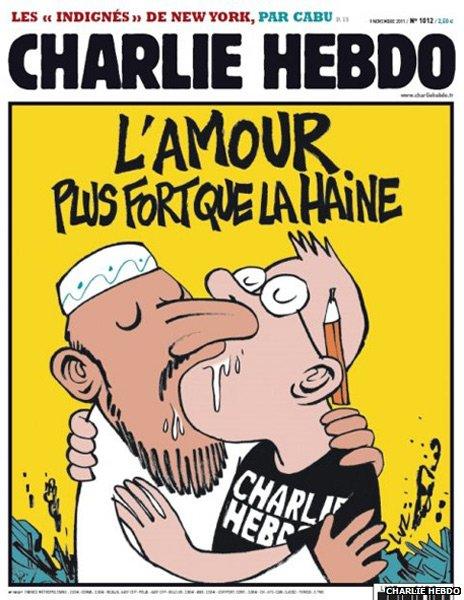

8 November 2011 issue: A Muslim man kisses a Charlie Hebdo male cartoonist under the caption “Love stronger than hate”, days after the magazine’s offices had been fire-bombed

Provocative cartoons

The paper has never sold in enormous numbers - and for 10 years from 1981, it ceased publication for lack of resources.

But with its garish front-page cartoons and incendiary headlines, it is an unmissable staple of newspaper kiosks and railway station booksellers.

Drawing on France's strong tradition of bandes dessinees (comic strips), cartoons and caricatures are Charlie Hebdo's defining feature. Over the years, it has printed examples which make its representations of Muhammad look like mild illustrations from a children's book.

Police would be shown holding the dripping heads of immigrants; there would be masturbating nuns; popes wearing condoms - anything to make a point.

As a newspaper, Charlie Hebdo suffers from constant comparison with its better-known and more successful rival, Le Canard Enchaine.

Both are animated by the same urge to challenge the powers-that-be.

But if Le Canard is all about scoops and unreported secrets, Charlie is both cruder and crueller - deploying a mix of cartoons and an often vicious polemical wit.

Charlie Hebdo offices - the magazine does not have a very big circulation

Ideological battles

True to its position on the far left of French politics, Charlie Hebdo's past is full of splits and ideological betrayals.

One long-standing editor resigned after a row about anti-Semitism.

Most of the staff - cartoonists and writers alike - go by single-name noms de plume.

Before Wednesday's attack the team was led Charbonnier - known as Charb - and another cartoonist called Riss. But everyone knows their real names.

The paper's origins lie in another satirical publication called Hara-Kiri which made a name for itself in the 1960s.

In 1970 came the famous moment of Charlie's creation. Two dramatic events were dominating the news: a terrible fire at a discotheque which killed more than 100 people; and the death of former President Gen Charles de Gaulle.

Hara-Kiri led its edition with a headline mocking the general's death: "Bal tragique a Colombey - un mort", meaning "Tragic dance at Colombey [de Gaulle's home] - one dead."

The subsequent scandal led to Hara-Kiri being banned. Its journalists promptly responded by setting up a new weekly - Charlie Hebdo.

The Charlie was not an irreverent reference to Charles de Gaulle, but to the fact that originally it also re-printed the Charlie Brown cartoon from the United States.

With Charlie Hebdo's leading figures gone - including the editor, as well as celebrated cartoonists and columnists - the magazine's future is unclear. In the short term, surviving staff have said they will put out next week's issue.

Editor-in-chief Gerard Biard - who was in London during Wednesday's attack - told RTL radio that Liberation newspaper would let his team use its premises and equipment.

A number of other news organisations, including the broadcasters Radio France and France television and the newspapers Le Monde and Le Canard Enchaine, have also pledged help.

But the long-term survival of one of France's iconic publications remains in the balance.