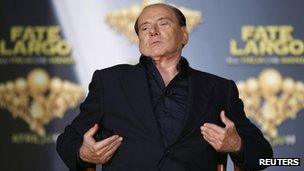

The last days of Silvio Berlusconi

- Published

- comments

The Berlusconi era draws to a close, but what comes next?

In the end power slipped away from the self-styled Il Cavaliere (The Knight). Under gloomy skies he had headed to parliament still believing that his coalition would stand behind him, still believing that he could coerce and cajole reluctant allies.

When the vote on the budget took place it was apparent his coalition had not held.

There had been defections.

Yes, the vote had passed, but it had been laid bare for all to see that he no longer commanded a parliamentary majority.

Silvio Berlusconi sat in the parliament - his usual exuberance had deserted him.

On a piece of paper in front of him he scribbled down his options. Resignation was one of them.

He also scribbled down the figure 8, the number from within his own party who had turned against him.

By the number he wrote the word traitors.

As he left the parliament, he let slip how hurt he was that people he had helped had turned against him.

He went off to see President Napolitano in the Quirinale (presidential palace).

They are two men with scant regard for each other.

After the conversation it was the president's office which said in a statement that Berlusconi would resign once the key austerity package - demanded by the European Union - had been passed.

A short while later the prime minister issued his own statement.

In the end, the priority was passing a reform package which was seen as essential to calming the markets.

If Berlusconi had stood down immediately it could have opened up a period of political in-fighting further unsettling financial markets.

The austerity measures will now go before the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

It is a process that could take weeks. It will allow time for manoeuvring.

Some feared it might enable the prime minister to seize the intervening period to build new alliances and perhaps engineer a way of staying in power.

But in an interview with one of his papers, he said that he would not be a candidate in any future election.

It does indeed look as if the man who has dominated Italian political life for the much of the past 20 years is going.

Silvio Berlusconi has shaped Italy, its culture, its TV shows and its attitude to women.

In his later years he resembled a Roman emperor, mired in sex scandals and, in his view, surrounded by plots and hostile magistrates.

But in the end his future was not written by his relationship with Ruby the heart-breaker, or bunga-bunga parties, but by the economy and fear.

Change arrived on the winds of panic, that Italy was heading for an abyss where borrowing costs were rising to a level where the country could need a bail-out.

Europe's increasingly dominant couple, President Sarkozy and Chancellor Merkel made it clear they did not believe that Silvio Berlusconi had the credibility to deliver reform.

His pending departure may ease the pressure of the markets but it won't change the fundamental problem.

Berlusconi had cast himself as a reformer who would modernise Italy. The story turned out differently.

Growth was flat for ten years and the country's debt mountain soared to 1.9 trillion euros. That problem has not gone away.

The EU has insisted on pension reform, that government assets be sold, that tax changes be made, that closed professions be opened up, that it be made easier to hire and fire.

The aim; to cut spending and boost growth - a difficult combination.

The opposition - knowing how unpopular many of these measures are - is pushing for a government of national unity.

Berlusconi and his party want immediate elections after the reforms have been passed.

They believe that a government of technocrats would be profoundly undemocratic.

All of this speaks to the difficulties that lie ahead.

There will be a battle over the future and an inevitable period of political instability.

There will be much criticism of the Berlusconi era; a lost period that became about the survival of a leader who increasingly identified his own interests as those of the state.

That being said it should be remembered that before Berlusconi, Italy was used to a government almost every year.

After his departure, Italy will struggle to create enduring coalitions that can transform this southern European country.

These are disturbing days for European democracy.

The euro-zone crisis is driving out elected leaders. European officials are telling elected governments what to do.

The head of the euro-group, Jean-Claude Juncker, demanded that the Greek opposition leader sign a letter pledging to carry out reforms.

Antonis Samaras, the leader of the opposition, snapped back "there is such a thing as national dignity."

Today a first group of European inspectors is arriving in Rome to check the accounts, to ensure reforms are being implemented.

For Italy this is a humiliation.

I will return to this in more detail in the future but there is rising concern that a Brussels elite is increasingly writing the economic policies of some of its states, insisting there is no alternative.