Spain election: Metro eyesore blights Granada

- Published

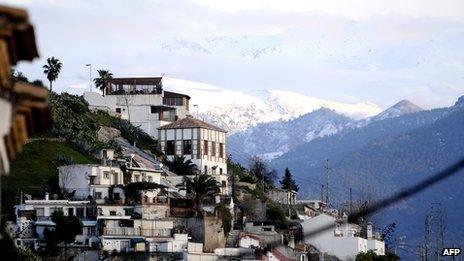

Granada: Views like this are little comfort for the armies of job-seekers

Nestling in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, the snow-capped mountain range outside Granada, the village of Pinos Genil is an idyllic setting.

A stream rushes through the valley as men sit chatting at cafe tables in the bright autumn sunshine. But all is not well in this part of Spain.

"This is the worst it's ever been," Vicky Soler, a serene woman in her 50s, tells us. Vicky speaks in clear, unaccented English. She went to school in London after her father, Victor, left Spain in the 1960s to search for work. In the last few years of General Franco's dictatorship there were few opportunities in Andalucia - people survived on subsistence farming and cars were a rare sight in the village.

Victor returned from London in the 1970s with enough money to buy a house and open the cafe by the river Genil. The boom years beckoned as Spain caught up with the rest of Europe.

But the bubble burst and with the current economic crisis, the family fears for their future. Vicky gets what work she can caring for elderly neighbours.

Her son Ricardo serves us coffee. "It's very difficult," he says. "There are no jobs anywhere. Unless you have a career already or are studying, you have to do something like become a waiter."

The family will be voting for the opposition conservative Popular Party (PP) in Sunday's election. They blame the current Socialist government for the country's situation. They spent too much money, says Vicky. "Then the prime minister lied to us," she says. "He said there was no crisis."

Thwarted ambitions

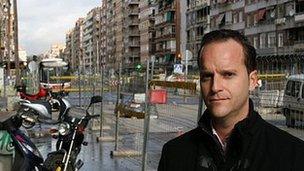

Henry O'Connell says the metro project has ruined a community in central Granada

But the crisis is laid bare down the road in Granada.

The city is a tourist Mecca, known for the magnificent Moorish architecture of the Alhambra Palace.

The city's authorities decided to construct a metro system to help deal with traffic congestion. Hundreds of millions of euros were invested in the project - some 15km (nine miles) of track, part over-ground, part underground.

But five years after starting, huge swathes of Granada are still a construction site - and workmen are few and far between. The money has run out. The original deadline of early 2012 for completion is a fantasy.

The governing Socialists admit the austerity measures they have implemented are painful, but insist they are the only way to avoid the political and economic instability that has plagued Italy and Greece in recent weeks. They promise they will maintain important social programmes - and warn that the PP would not do so. The PP, say the Socialists, are hiding plans for harsher cuts behind a vague manifesto.

"It was meant to be a beautiful wide avenue with lots of trees," says Henry O'Connell Sanchez, gazing at Granada's Camino de Ronda. Originally one of the city's busiest streets, it is now one vast building site, littered with wire fencing, concrete blocks and holes in the ground.

Camino de Ronda: Sad symbol of the collapse of Spain's construction boom

Henry was born here and now runs an English academy. "The businesses are all closing or are already closed - we're talking family businesses who've been working here all their lives."

In fact, 1,262 businesses in and around Granada have had to close as a result of the metro project, according to a local newspaper, Granada Hoy. And after the regional government stopped funding the project, the contractors had to lay off 90% of their workers. That in turn is another bitter blow to the construction industry, which has already borne the brunt of Spain's crisis.

Anti-eviction campaign

Antonio Redondo, 32, was laid off from his job in the building industry two years ago. When his money ran out he could no longer afford his mortgage payments. A meeting with his bank manager was a waste of time, he tells me. "He didn't offer any solution. The bank told me they would repossess my house, and leave me with a huge debt to pay."

That debt was over 100,000 euros (£86,000). Despite paying his mortgage on time for six years, the devaluation in property value and a peculiarity of Spanish mortgage law meant Antonio was going to be left homeless, in enormous debt and without any income - or hope of finding a job.

In desperation and with no apparent legal recourse, Antonio turned to "Stop Desahucios" - Stop Evictions. The group sprang up around Spain after the "Indignados" (the Indignants) protest movement captured the nation's imagination. As unemployment soars and state help is cut, more and more people face losing their homes. Cases like Antonio's are becoming common - and the protesters are getting creative.

The Soler family in Pinos Genil blame the Socialists for the country's debt crisis

"We found a guitar player and singer - and someone else to dance," says Antonio with a grin. "About fifty of us went into the bank one Friday afternoon with signs and started singing."

The protest embarrassed the bank - and it phoned three days later offering to negotiate terms on his house. Antonio is resigned to losing his house but crucially it seems that the bank is prepared to waive the enormous debt.

Antonio and his friends in the Granada protest movement reflect a widespread opinion when they say they will not vote for either of Spain's main parties. The crisis is the fault of the politicians, they say, and voters should look to radical alternatives.

"Our success proves there is a different way," he says.

The Popular Party's plans are short on detail, but Vicky in Pinos Genil still has confidence in them. "I trust them with the economy, although I don't envy Mariano Rajoy," she says, referring to the PP leader, tipped to become prime minister. "I wouldn't want to be in his skin. It's going to be really difficult."

- Published7 December 2011

- Published15 November 2011

- Published17 November 2011