Struggling Hungary knocks on IMF's door again

- Published

Some poor Hungarians get food handouts from Krishna volunteers

Hungary is not in the eurozone but it has joined the club of Europe's debt casualties and it too is seeking IMF help.

The government's decision last week to reopen talks with the International Monetary Fund for a credit lifeline has not gone down well here.

In 2008 Hungary got a 20bn-euro (£17bn; $27bn) standby loan from the IMF, the World Bank and European Union.

The opposition sees the latest move as proof that the conservative Fidesz party's economic policy is bankrupt.

The government insists that the "flexible credit line" it is hoping to negotiate by the New Year will be just a safety net, to reassure investors and ensure growth.

But few believe the economy will grow next year, and many fear even IMF support will not be enough, if troubles deepen in the eurozone, on which Hungary depends.

Government supporters also feel betrayed because barely a year ago Prime Minister Viktor Orban had declared a "freedom fight" against the IMF.

Only three days before the government announcement, Economy Minister Gyorgy Matolcsy called the IMF "that three-letter institution".

And a commentator in the staunchly pro-government daily Magyar Nemzet called turning to the IMF "an act of capitulation" similar to a restaurant bowing to a blackmailer's demand to pay protection money, or watch his business burnt to the ground.

Harsh market lessons

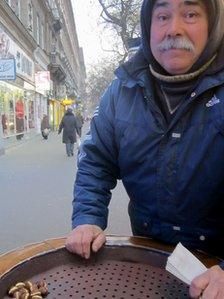

When was your last good year? I asked Imre, a man selling the last of the autumn's chestnuts on the Great Boulevard in Budapest.

"Nineteen eighty-nine," he said, clearly not joking.

This Budapest chestnut seller complains of two decades of austerity

Hungary was at the heart of the upheavals in 1989 that brought down communism in the former Soviet bloc.

While many European countries began introducing austerity measures after the 2008 financial crash, Hungarians date their belt-tightening to 1995. That was when the finance minister of the Socialist-Liberal government, Lajos Bokros, introduced an infamous package of measures.

While its ex-communist neighbours saw dynamic growth after joining the EU in 2004 Hungary struggled.

Since 2006, 140,000 public sector jobs have been axed, according to Janos Arva, President of the Civil and Public Servants' Union MKKSZ. He fears another 30,000 jobs will go next year, and his union has called on its members to demonstrate on 3 December.

"We want to tell the public that what the government is doing will bring the country to its knees. We are not against reform. We want a working public administration. We have made 140 proposals since this government came to power, but they just don't listen."

Prime Minister Orban turned to the IMF again because of the downward slide of the national currency, the forint, and fears that ratings agencies would downgrade government bonds to junk grade. Since the government announcement, the forint has risen again, and a successful bond auction was held this week.

The yield on the bonds - the rate the government has to pay to service its debts - was 6.63%, just below the 7% threshold which in Italy's case triggered the departure of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Swiss franc debts

According to economist Zoltan Pogatsa, austerity measures already taken by the government are in line with the usual IMF recipes. "So I don't expect any drastic change of policy," he said. Sales tax (VAT) will increase next year to 27% - the highest in the EU. The flat tax of 16%, the centrepiece of Fidesz economic policy, has been supplemented with additional taxes which are extremely unpopular.

One peculiarly Hungarian feature of the crisis is debt denominated in foreign currencies - 1.2 million people have such mortgages, mainly in Swiss francs.

In a 1930s apartment block electrician Janos Szanto stands on a ladder, twisting wires expertly into the wall. He is scornful of a government scheme that allows people to pay off mortgages with one lump sum at far better than market rates.

The scheme has infuriated banks and Mr Szanto says it does not help him at all. "If I had such savings, I would never have taken a loan in the first place!"

Several hundred thousand better-off debtors are nevertheless trying to take advantage, and raise the money needed by the end of the year.

The government meanwhile is rushing bills through parliament, including reform of the electoral law, of public administration and the labour code.

"By (the next elections in) 2014, I would like to re-establish the Hungarian state as a public administration above partial interests, above vested interests, and serving the public good," Deputy Prime Minister Tibor Navracsics told the BBC.

Trade union leader Janos Arva said "we're absolutely in favour of modernisation of the state - but that will not be achieved by calling public servants lazy, unwilling to work conscientiously, overpaid, or too numerous".

- Published21 November 2011

- Published20 June 2011

- Published17 June 2011