New Icelandic volcano eruption could have global impact

- Published

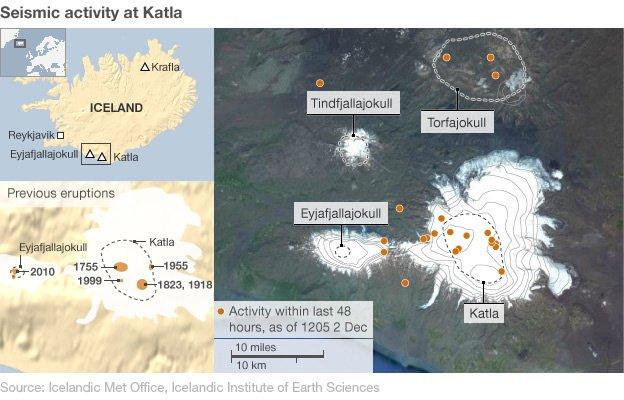

Ford Cochran says that the 500 or so tremors in and around the caldera of Katla just in the last month suggest "an eruption may be imminent"

Hundreds of metres under one of Iceland's largest glaciers there are signs of a looming volcanic eruption that could be one of the most powerful the country has seen in almost a century.

Mighty Katla, with its 10km (6.2 mile) crater, has the potential to cause catastrophic flooding as it melts the frozen surface of its caldera and sends billions of gallons of water surging through Iceland's east coast and into the Atlantic Ocean.

"There has been a great deal of seismic activity," says Ford Cochran, the National Geographic's expert on Iceland.

There were more than 500 tremors in and around the caldera of Katla just in October, which suggests the motion of magma.

"And that certainly suggests an eruption may be imminent."

Scientists in Iceland have been closely monitoring the area since 9 July, when there appears to have been some sort of disturbance that may have been a small eruption.

Eruption 'long overdue'?

Even that caused significant flooding, washing away a bridge across the country's main highway and blocking the only link to other parts of the island for several days.

"The 9 July event seems to mark the beginning of a new period of unrest for Katla, the fourth we know in the last half century," says Professor Pall Einarsson, who has been studying volcanoes for 40 years and works at the Iceland University Institute of Earth Sciences.

"The possibility that it may include a larger eruption cannot be excluded," he continues. "Katla is a very active and versatile volcano. It has a long history of large eruptions, some of which have caused considerable damage."

The last major eruption occurred in 1918 and caused such a large glacier meltdown that icebergs were swept into the ocean by the resulting floods.

The volume of water produced in a 1755 eruption equalled that of the world's largest rivers combined.

Thanks to the great works of historic literature known as the Sagas, Iceland's volcanic eruptions have been well documented for the last 1,000 years.

But comprehensive scientific measurements were not available in 1918, so volcanologists have no record of the type of seismic activity that led to that eruption.

All they know is that Katla usually erupts every 40 to 80 years, which suggests the next significant event is long overdue.

Eyjafjallajokull's relatively small eruption in 2010 halted air traffic across Europe

Katla is part of a volcanic zone that includes the Laki craters. In 1783 volcanoes in the area erupted continuously for eight months, generating so much ash, hydrogen fluoride and sulphur dioxide that it killed one in five Icelanders and half of the country's livestock.

"And it actually changed the Earth's climate," says Mr Cochran.

"Folks talk about a nuclear winter - this eruption generated enough sulphuric acid droplets that it made the atmosphere reflective, cooled the planet for an entire year or more and caused widespread famine in many places around the globe.

"One certainly hopes that Katla's eruption will not be anything like that!"

The trouble is scientists do not know what to expect. As Prof Einarsson explains, volcanoes have different personalities and are prone to changing their behaviour unexpectedly.

"When you study a volcano you get an idea about its behaviour in the same way you judge a person once you get to know them well.

"You might be on edge for some reason because the signs are strange or unusual, but it's not always very certain what you are looking at. We have had alarms about Katla several times."

Changing climate

He says the fallout also depends on the type of eruption and any number of external factors.

Iceland is the only place where the mid-Atlantic rift is visible above the surface of the ocean

"This difficulty is very apparent when you compare the last two eruptions in Iceland - Eyjafjallajokull in 2010 and Grimsvotn in 2011.

"Eyjafjallajokull, which brought air traffic to a halt across Europe, was a relatively small eruption, but the unusual chemistry of the magma, the long duration and the weather pattern during the eruption made it very disruptive.

"The Grimsvotn eruption of 2011 was much larger in terms of volume of erupted material.

"It only lasted a week and the ash in the atmosphere fell out relatively quickly.

"So it hardly had any noticeable effect except for the farmers in south-east Iceland who are still fighting the consequences."

Of course, volcanoes are erupting around the world continuously. Scientists are particularly excited about an underwater volcano near El Hierro in the Canary Islands, which is creating new land.

But Iceland is unique because it straddles two tectonic plates and is the only place in the world where the mid-Atlantic rift is visible above the surface of the ocean.

"It means you actually see the crust of the earth ripping apart," says Mr Cochran. "You have an immense amount of volcanic activity and seismic activity. It's also at a relatively high latitude so Iceland is host to among other things, the world's third-largest icecap."

But the biggest threat to Iceland's icecaps is seen as climate change, not the volcanoes that sometimes melt the icecaps.

They have begun to thin and retreat dramatically over the last few decades, contributing to the rise in sea levels that no eruption of Katla, however big, is likely to match.

- Published25 May 2011

- Published12 August 2011