Germany's neo-Nazi underground

- Published

The village of Jamel is believed to be home to far-right activists

Ten murders blamed on a neo-Nazi underground cell have raised fresh fears about far-right extremism in Germany. BBC Radio One Newsbeat's Sima Kotecha went to investigate.

It is difficult to digest that places like this still exist in modern-day Germany.

Jamel - a tiny village encircled by fields - sits in the northeastern state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania on the coast of the Baltic sea, and is believed to be home to a group of right-wing extremists.

"I think you should not be here because you don't look like the people from this area".

Not the most reassuring words from my German companion, Horst Krumpen, the Chairman of the Network for Democracy, Tolerance, and Humanity in the neighbouring town of Wismar.

There was no disguising his concern for my safety because of my racial origin.

As we began our walk into Jamel, the trepidation set in. Attack dogs behind fences barked incessantly, while the wind whistled loudly.

The large metal shutters on most of the windows relayed the message - this is a private place. It felt sinister.

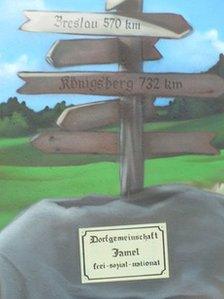

The Nazi-era propaganda became visible inside a cul-de-sac of only ten houses or so. We were met by a mural of a rock with the words: "Jamel village community - free, social, national".

From a rock sprouted a sign pointing to the former German cities of Koenigsberg (now Kaliningrad in Russia), and Breslau (now Wroclaw in Poland). The latter was the last Nazi stronghold during the Second World War.

There have been reports of pro-Hitler parties here during the summer months where guests sing "Hitler is my Fuehrer", and chant "Heil" around a bonfire. The village is in one of only two states where the far-right National Democratic Party (NPD) has a seat in parliament.

It is places like Jamel that are increasingly worrying the German Bundestag - especially after recent revelations of a neo-Nazi terror cell in the eastern town of Zwickau which operated under the name "National Socialist Underground" (NSU).

Investigators believe it was behind a string of racially motivated murders between 2000 and 2006 in which eight Turks and a Greek were killed. A policewoman was murdered in 2007.

Chancellor Angela Merkel said the murders brought "shame" on the nation and were a "disgrace".

Intelligence agencies are under fire for failing to spot the cell and are being accused of turning a "blind eye" to the threat from the far-right.

A recent poll has revealed that 74% of Germans want the NPD outlawed, but an attempt to do that in 2003 failed when the case was rejected in the Federal Constitutional Court.

There is scepticism over whether a second attempt will be successful.

Icy stare

On a chilly day in Berlin, the Christmas spirit is in full swing with the local community setting up festive markets along the main roads.

But tucked away from the hustle and bustle is a 34-year-old former neo-Nazi who has agreed to meet us on condition that we do not reveal his identity.

"We stirred up discontent and unrest. Violence was part of the scene, the whole ideology of the movement is based on violence, and it is seen as a legitimate means to reach political targets.

"The inhibition threshold to go as far as killing people is very low," he says.

With a solid, icy stare he tells us he never killed anyone but came close to it.

"I still cannot say to this day if I would have killed, but I realised later that just by punching someone in the face, or hitting them with brass knuckles, I could have killed them," he says.

This man escaped the tight-knit underground community that glorifies Hitler's Third Reich but anti-fascist charities are worried a growing number of young men are being lured into the far-right, especially amid tough economic times.

Bernd Wagner is the CEO of EXIT-Germany, an organisation that helps right-wing extremists leave the movement.

Nazi-era propaganda attests to the far-right presence in Jamel

"We are seeing a decrease of right-wing extremists in general but at the same time there is an increase of neo-Nazis and organised right-wing extremists.

"Plus there is a tendency in the population of sympathising with their ideas and ideology which is also increasing," he says.

"People are frightened"

Kreuzberg in Berlin is renowned for its vibrant outdoor Turkish markets - and authentic Arab cuisine. But people here are anxious.

Dervis Hizarci works as a guide in a local Jewish museum, and is also an active board member of the Turkish community.

"We are not sure what happened in the past, why the media didn't show the mistakes of the intelligence agencies and tell the Turks what happened, but this makes all the Turks very uncertain," he says.

His friend Sayin Alim is an estate agent, and joins us for some Turkish potato bread and tea in a brightly lit coffee shop.

"People are frightened. The people are now determined to keep among their own community.

"They are not open to other communities now or the German culture," he says.

But the threat from the far-right in cosmopolitan Berlin seems remote.

It leaves investigators questioning whether places like Jamel are a one-off or whether they illustrate a wider sickness in the state of Germany.

- Published1 December 2011

- Published29 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published20 November 2011