European viewpoints: The EU summit deal

- Published

As the 27 countries of the EU respond to the deal hatched at the Brussels summit, political correspondents from France, Germany and Poland consider whether or not it was a success and what it will ultimately mean for the future of the European Union.

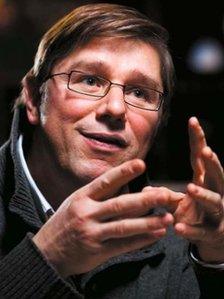

Jean Quatremer, Brussels correspondent, Liberation, France

The eurozone has wanted to show it is determined to create a strong budgetary and economic integration with enormous powers of constraint given to the European Commission, something unimaginable two years ago.

One can really talk about a leap towards federation, even if it would have been preferable to do it within European treaties. The Brussels accord also shows the strong attraction of the euro despite the current crisis: apart from the UK, all EU states have decided to sign this new treaty, including Denmark, which benefits from an opt-out.

After 12 summits meant to bring a definitive solution to the euro crisis, I am extremely cautious, given how irrational the markets have been. But this new treaty is just one element in the solution: the recapitalisation of European banks, more modest than the markets have foreseen, will allow a credit crunch, and thus a recession, to be avoided.

Likewise the decision of the European Central Bank to provide unlimited three-year funds at a rate of 1% is going to allow them to buy sovereign debt again: with interest rates above 1%, they are going to earn money, which will regulate the credit pump.

The only loser is the UK, which has put itself in a corner. It is even a real diplomatic Pearl Harbour. None of the UK's natural allies has followed it in its attempt to repatriate powers and sabotage the treaty. There is no precedent for 26 against 1 in EU history, which underlines how bad a diplomat David Cameron is.

Its position in the EU will be weakened in a grave and lasting way. In effect, the willingness of the 26 to pursue integration is going to proceed through further financial, fiscal and social integration. Only in the fiscal domain does London have the right of veto.

By isolating itself, it thus risks having to support decisions it does not want, which can only hasten its exit from the EU, an exit which now seems ordained to me. I am not at all sure that would be in its interest. But I respect Great Britain's right to suicide.

Dominika Cosic, Brussels correspondent, Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, Poland

I have very mixed feelings about the deal because for me it's positive that we avoided treaty change which could be very risky and take two years or more to implement. That would have meant not being able to fight the EU's main problem, the debt crisis.

But it's also very difficult to say what has been agreed as there appear to be more questions than answers. It's an open question what fiscal union will mean.

Politically, the Polish opposition is against it and the government supports it although neither really knows the content of the deal.

The summit didn't appear to solve any problems. Poland already has fiscal discipline built into its constitution and we'll have to wait for the new governments of Greece, Italy and Spain to implement their reforms.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk wants to be at the heart of Europe and has come out in support of France and Germany.

A few days ago Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski gave a strong speech in favour of integration. The conservative opposition argues he should have discussed it in Poland first and believes we should keep closer to the UK position. Even if Mr Tusk had been against joining the euro, French President Nicolas Sarkozy reminded him at the October EU summit that Poland had to join.

The conclusion of the summit has shown that intergovernmental support is stronger than the position of the institutions. The Commission had been very much opposed to having new treaties but France and Germany are now the leading powers of the EU and want to change the EU. Then you have the UK position, with some support from the Czechs.

The only clear message from the summit was that the UK wants to distance itself from integration.

No-one is surprised by the position taken by UK Prime Minister David Cameron as it was well known that Britain would not support closer co-operation. In the next few months or year, I think the UK will have to decide whether it wants to remain a full member of the EU.

Either there will be a referendum or, if the other 26 members of the EU support the changes, Britain will be left on its own. I was told by some British Conservative MEPs this week that they felt there would be a referendum and the British people would vote No.

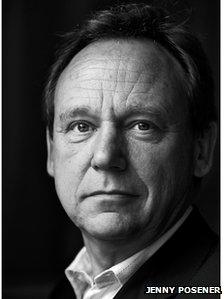

Alan Posener, political correspondent, Die Welt, Germany

I think this deal is just another fix - and as it is going in the wrong direction it is not a good deal at all.

As there is no agreement of all 27 EU members - especially not Britain - we are heading for two different treaties within Europe, which will split. And all because Germany demanded treaty changes.

Why were these treaty changes necessary? We already have the so-called "debt brake" - it is the Maastricht Treaty. This has been agreed on by all 27 states - but has been broken again and again for the simple reason that the minute a country needs the money they will find it.

It is an exercise in futility - if Maastricht didn't work, why would this? To risk breaking up Europe for something that won't work seems counter-productive.

Though if anything this deal will make the crisis worse, I don't actually think the euro will go down the drain because a euro break-up would be worse than anything else. But I don't know for how long countries such as Greece and Italy can take these austerity measures.

It seems to me that it is pointless, simply saying that we'll put a "debt brake" in the constitution and if countries go beyond that the European Court of Justice will say they are in breach and impose fines - as they wouldn't be able to afford to pay anyway.

Europe may speak German now, as a German government minister recently commented, but the markets speak English - and they don't give a damn about language. They just want to make sure their investments are safe. And I don't see that being the case under this deal.

Angela Merkel is covering her tracks. She is the main person responsible for this problem, though she is now pretending it wasn't her.

I think the Chancellor played a very bad hand at the summit. The French gave in to her wishes because they see a "debt brake" as a formal thing - they hope to get what they want, which is eurobonds, down the line. I think the French played a pretty good hand.

David Cameron was in an unfortunate position - he had to appease his own party and not appear to be too Europhile. But I think he hasn't got anything out of the summit, apart from being out of the deal.

It's a pity he was so concentrated on British issues as there might have been a way for him to negotiate more deregulation across the board. But that wouldn't have looked as good to the Tory Eurosceptics.