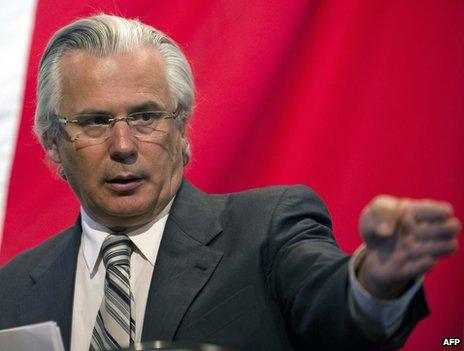

Profile: Judge Baltasar Garzon

- Published

Rarely can a modern-day judge have stirred as much controversy as Spain's Baltasar Garzon.

To some he is a crusading hero, taking on dictators and terrorists on behalf of the world's oppressed.

To others he is a left-wing busybody obsessed with self-promotion.

While he was pursuing foreigners with questionable human rights records, the criticism directed at him was mainly just that - criticism.

But by delving into Spain's own murky past, he provoked more strident opposition, and he was charged with over-reaching his judicial powers.

He has now been convicted of ordering police to carry out an illegal wire-tapping operation and faces an 11-year suspension from practising law.

He cannot appeal against the decision and his career as a judge could now be over.

'Changed the world'

Until he was suspended in 2010 because of the case against him, Mr Garzon served as one of six investigating judges for Spain's National Court which, like many other European countries, operates an inquisitorial system as opposed to the adversarial system used by the US and UK.

The investigating judge's role was to examine the cases assigned to him by the court, gathering evidence and evaluating whether the case should be brought to trial. He would not try the cases himself.

Born on 26 October 1955 in Villa de Torres in southern Spain, he became a provincial judge at 23, and joined the National Court at the age of 32.

He came to worldwide attention in the late 1990s, when former Chilean military ruler Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London on his initiative.

The judge was acting under Spain's principle of universal jurisdiction, which holds that some crimes are so grave that they can be tried anywhere regardless of where the offences were committed.

Pinochet headed Chile's military regime from 1973-1990, when about 3,000 people were killed or went missing in his crackdown on leftist opposition.

Pinochet was arrested in the UK in 1998 and detained for 18 months while Spain's extradition request was considered. In the end, it was ruled he was too frail and he was allowed to go home.

Judge Garzon was also behind the trial in Spain of Argentine ex-naval officer Adolfo Scilingo, who was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to 640 years in jail in April 2005.

In another case, he compiled a 692-page indictment in 2003 which called for the arrest of suspected terrorists including Osama Bin Laden. Eighteen were tried in Madrid, convicted of belonging to an al-Qaeda cell and sentenced to long prison terms.

According to Reed Brody, spokesman for a New York-based Human Rights Watch, the arrest of Pinochet inspired victims of abuses, especially in Latin America, to challenge and win the repeal of laws giving amnesty to perpetrators of atrocities committed by military juntas.

"Garzon changed the world,'' he said.

However, Mr Garzon's investigations closer to home have proved more controversial, on both sides of Spain's political divide.

Civil war taboo

When he led an investigation into death squads organised by the Socialist government in the 1980s to fight Basque separatists, the revelations were credited with helping the centre-right defeat the left in 1996 elections.

Judge Garzon was also active in Madrid's crackdown on the Basque separatist group Eta and is reported to have been on the group's list of assassination targets.

But his investigations into the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship - long a taboo subject - appear to have earned him the greatest enmity.

In October 2008, he launched an unprecedented inquiry into "crimes against humanity" during the Franco era, promising to investigate the disappearance of tens of thousands of people and ordering the excavation of mass graves.

A right-wing civil servants' union accused him of over-reaching his judicial powers by breaching the official amnesty that drew a line under the Franco era in 1977.

Under heavy pressure, he withdrew the investigation but he was charged with violating the amnesty law.

He also faced two more cases: in one he was accused of dropping an investigation into the head of Spain's biggest bank, Santander, after receiving payments for a course sponsored by the bank in New York.

He was also charged with illegally authorising police to record the conversations of lawyers with their clients - for which he has now been convicted and suspended for 11 years.

Jose Antonio Martin Pallin, a judge emeritus at the Supreme Court, said there were many people in Spain who wanted revenge on Mr Garzon.

Among other things, he told the Associated Press news agency, there was envy among judges who were used to discretion and modest salaries, and disliked his lifestyle of jetting around the world to give well-paid lectures on human rights.

He described fellow judges' thinking as "this man is going to get it now, for all his enjoyment, for his speaking fees''.

- Published18 August 2011