Portugal brings back rare guard dogs to tackle wolves

- Published

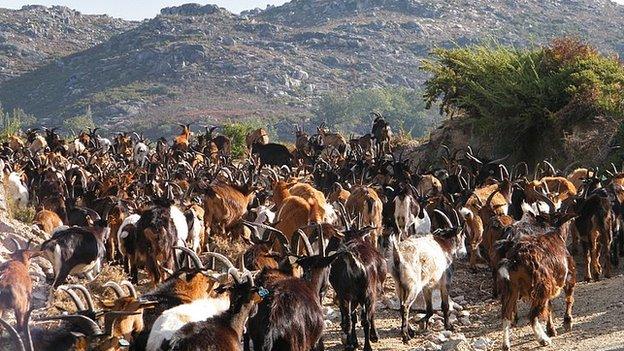

Alfredo’s goats head off to graze in the mountains

For centuries, guard dogs worked alongside livestock farmers in the mountains of Portugal to protect their animals from the Iberian wolf.

But the dogs fell out of favour when shooting and poisoning came to be seen as a quick and easy method of controlling the wolves at the turn of the 20th century. Now that wolves are protected under Portuguese law, some of the country's oldest dog breeds are being used to help struggling farmers co-exist with the predators.

Portuguese wolf conservation organisation Grupo Lobo is encouraging the farmers to turn back the clock and work with the rare dogs, which fiercely protect the flocks under their care and chase off attacking wolves.

The Iberian wolf is now fully protected by Portuguese law

Since 1988 there has been a ban on killing or harming wolves. Nevertheless, the wolves remain under constant threat, often from desperate farmers resorting to desperate means.

Some 300 Iberian wolves (Canis lupus signatus - a slightly smaller subspecies of the European grey wolf) survive in the northern and central highlands of Portugal.

"We are encouraging farmers to use traditional livestock guarding dogs once again, not only to cut down on livestock attacks which will help farmers tolerate the wolf more, but also to bring these traditional Portuguese dog breeds back from the brink," explains Silvia Ribeiro, a biologist with the conservation project.

Dog breeds such as the Cao de Castro Laboreiro, Cao da Serra de Estrela and Cao de Gado Transmontano were highly valued in the past for their protective instinct and innate ability to bond strongly with the animals under their care.

"Their behaviour is quite unlike that of herding dogs. It is part of their character and breeding to bond with and protect their flock fiercely," Ms Ribeiro says. "They are always actively on the look-out, sniffing for signs of trouble and watching for livestock in distress.

A Cao de Castro Laboreiro guarding dog protects its flock

She says that if under attack, the dogs will stand between the flock and the wolf, barking and chasing the wolf away. Their sense of smell is so powerful they can even distinguish between the goats of their own flock and another.

For livestock farmers such as Alfredo Goncalves, who farms 450 goats on the edge of Peneda-Geres national park, the project is proving effective.

"I lose about 80 goats per year to wolves," he says.

"Government inspectors come and evaluate any kills and we are paid for our lost livestock but often it can take one to two years and that is a long time to wait, especially in this economic climate."

Mr Goncalves says he is happy to live alongside the wolves but their attacks have a serious impact on farmers who earn very little.

His small monthly income of approximately 500 euros (£415, $658) depends largely on selling the goats' kids for meat.

To help cut down on wolf attacks, Grupo Lobo gave him a two-month-old Castro Laboreiro dog called Tija 18 months ago.

Farmers participating in the project are given a free dog but sign a strict contract, agreeing to its training, how it is cared for and used, and submit to regular research and monitoring by Grupo Lobo.

So far, 300 dogs have been placed with 170 livestock breeders.

Tija now lives with Alfredo's goats in a compound at night and stays with the flock while grazing in the mountains each day. His breed comes from a village north of the national park and was once commonly used in the area but is now very rare.

The dogs bond so strongly with the flock under their care that biologists at Grupo Lobo speak of female dogs that have abandoned their own puppies to suckle new-born goats.

A surprisingly gentle and friendly dog, Tija is clearly valued by Alfredo who has recently asked the conservationists to provide him with a second guard dog.

Tija waits patiently to take part in a working breeds’ dog show

"In each wolf attack, we usually lose one or two goats," he says.

"Sometimes, when the flock is grazing and small groups stray and wolves attack, we can lose 10 or more animals. It is devastating. But since the arrival of Tija, goat killings are down by a quarter."

To provide full protection for a flock of 500 animals, three or four guarding dogs are needed and some farmers have been reluctant to take on the new dogs and all the costs and effort involved.

"It hasn't been plain sailing getting farmers on board," said Ms Ribeiro. "They are still having to adapt to the Iberian wolf as a protected species."

After hundreds of years of it being viewed as a pest, that's a difficult mindset to conquer, she concedes.

- Published18 January 2011

- Published6 September 2011