Portuguese jobseekers change the face of Swiss village

- Published

The eurozone financial crisis has left nearly 17 million people out work, many of whom are now looking further afield to places like Switzerland. As the BBC's Imogen Foulkes reports from Taesch, this is changing the face of some very traditional Swiss communities.

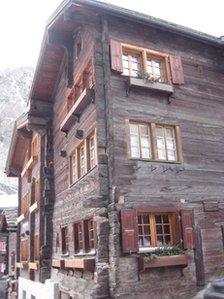

At first sight, the tiny village of Taesch is a typical Alpine community, with old wooden houses, a church, a shop and a bakery.

But nowadays the most common language on Taesch's streets is not the native German, but Portuguese, and the local shop is doing a brisk trade in Portuguese specialities such as salt cod and red wine.

Although Swiss voters said no to full EU membership more than 20 years ago, Switzerland has signed up to various EU policies, including those governing the free movement of people and labour.

Now, Switzerland's low unemployment rate, just 2.8%, its comparatively high salaries and its healthy economy are attracting thousands of people from across Europe.

More than 140,000 immigrants arrived in Switzerland last year, a rise of 6% on 2010.

Most of them came from EU member states, in particular those worst affected by the crisis in the eurozone, including Portugal.

Yolande Carvalho first arrived in Taesch more than 15 years ago, and remembers when there were just a handful of non-Swiss in the village.

Now, things are very different.

"We, the Portuguese, are half the population," she explains. "When you walk up and down the streets, the shops, everywhere you can speak Portuguese."

In the last year, she has seen more and more of her fellow citizens make the move north.

"There are no options [for young people]," she says.

"If it's a choice between working for 700 euros a month (£590; $920) in Portugal and barely being able to pay the rent or buy food, then you're better off coming to Switzerland."

Dishwashers and bedmakers

Taesch's population now stands at 1,270, more than 700 of whom are foreign, most of them Portuguese.

Marcel left Portugal when he couldn't find work

But why should so many people from Portugal choose a tiny, isolated village deep in the Swiss Alps? The answer lies just a couple of kilometres further up the valley, in the booming resort of Zermatt.

Here there are more jobs than the locals are able to do: in the hotels, restaurants, and in the building trade.

What is more, cleaning hotel bedrooms or wiping bar tables is not work most Swiss want to do any more. Across the country, the tourist industry relies on immigrant labour.

Twenty-year-old Marcel left school in Portugal this year and had hoped to find work there.

"I looked around but there was nothing for me in Portugal," he says. "I had this chance, and I took it."

Marcel's chance is washing dishes in a Zermatt restaurant with two other young men from Portugal.

"I miss my family a lot," he says, "my friends, my home, my town, everything. It's hard but I can do it, I'm strong."

While newcomers may be feeling homesick, the locals are somewhat uneasy about the high number of immigrants.

In Taesch's school the most common language is Portuguese and, in the kindergarten, German is now spoken by only a tiny minority.

"There are 13 children," local integration officer Patricia Zuber says of one class, "and just three of them speak German".

Ms Zuber's job, newly created in Taesch, involves setting up subsidised language courses for immigrants, offering advice on Swiss laws and local life to newcomers, and organising get-togethers where both communities can meet.

"It's important that people here meet each other as people," she explains, "and not as a man from Portugal, or as a man from Switzerland".

"But," she admits, "it's about difficult things. It's about the culture".

Culture clash

Yolande Carvalho, who, as head of the local Portuguese community centre works closely with Ms Zuber, agrees that what might seem like small cultural differences can be big stumbling blocks in the way of village harmony.

Living side by side can cause friction

"Here, there are rules everywhere," she says with a smile. "And, you know, the Portuguese can be very loud. That's the way we are."

"The locals go to bed at 21:00, even 20:30, and they don't really appreciate it if we are up making a noise until 22:00. So that's something we have to adapt to."

Village elected official Claudius Imboden agrees that the new Taesch is a difficult adjustment for many local people, but believes acceptance and integration are the only realistic options.

"This used to be a farming village," he says. "But now we make our living from tourism and the building industry, and the immigrants are helping us to make that living. We need them."

He admits that some people in the village are unhappy with the changes but argues that they have to live somewhere.

What is more, he points out, the 21st Century wave of immigration to Taesch has causes which local people should be able to relate to.

"One hundred years ago this village was very poor," he explains. "People had to leave to find a living; people from Taesch went everywhere, even to South America. The same thing is happening now, but in reverse."

Referendum for change?

On a national level, the mood is not so positive. Opinion polls show many Swiss would like to opt out of the Schengen agreement on the free movement of people and re-introduce immigration quotas.

The right-wing Swiss People's Party (SVP) has collected enough signatures to hold a referendum on opting out, and SVP MP Luzi Stamm confidently expects voter support.

"Everybody underestimated immigration into Switzerland," he says.

"It's much, much larger than anybody thought. I think we have to stop free movement in the sense that it's not controllable anymore, we have to set limits and we have to control it."

For communities like Taesch, though, it will be difficult to turn the clock back, and Mr Imboden believes even the local Swiss residents may not want to.

"Without the immigrants, we probably wouldn't have a school here anymore, because we don't have enough children."

Ms Carvalho says the relationship between locals and incomers is improving all the time.

"I see it on the streets," she explains. "The older people, when they hear the Portuguese kids shouting or laughing, they say 'oh, that's the Portuguese'."

"But now they are smiling when they say it, because these are children, and they are joyful."

- Published23 October 2011

- Published30 December 2011

- Published29 February 2012