Germany's new breed of neo-Nazis pose a threat

- Published

The security services in Germany are scrambling to track down and arrest far-right fugitives and Germany's federal and state interior ministers have announced they are taking concrete steps towards banning the country's far right National Democratic Party, the NPD.

This comes after a public outcry following revelations in November that a neo-Nazi cell had apparently been able to go on a nationwide spree of racially motivated murders over several years, under the noses of the German intelligence services.

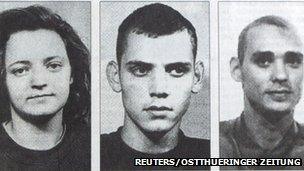

The group of three are being held responsible for the deaths of eight Turkish and one Greek immigrant between 2000 and 2006, as well as a German policewoman in 2007.

Yet the existence of the group, dubbed the Zwickau cell after the name of the town where they spent most of their time in hiding, only came to light in November when two of its members died in an apparent joint suicide or murder-suicide and the third handed herself in to the authorities.

The NPD has been linked to the group, though the allegations have yet to be accepted in a court of law.

The trio had made a DVD in which they boasted of the killings and said they had acted to serve the German nation and its people, describing themselves as the National Socialist Underground - echoing the national socialism (Nazism) of Hitler's Germany.

The story of the killers has dominated headlines in Germany for months now and given rise to one of the biggest scandals in post-war Germany.

It turns out intelligence agencies had had the group under surveillance for years, and even found a bomb-making factory in their garage back in 1998.

So why were the trio not stopped earlier? Why were they allowed to disappear and then stay underground? And why was it that security services blamed the murders on the Turkish mafia at the time? A right-wing motive was never investigated.

The failures have prompted some to ask whether there is more than incompetence to blame, whether Germany's police and security services contain elements sympathetic to the far right - an accusation the institutions vehemently deny.

A parliamentary inquiry is currently under way into their activities, and Newsnight has seen a secret internal report revealing serious blunders by law enforcement agencies.

Police limitations

When we spoke to Peter Altmaier, a senior official in Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democrat party, he admitted that mistakes had been made:

"You have to know Germany is a federal state, and competencies are shared and divided between federal and state levels... and because we have drawn the lessons from the Nazi dictatorship, we have very limited powers of police and security institutions.

The neo-Nazi group, which has been dubbed the Zwickau cell, operated for more than 10 years

"There have been hints and indications of right-wing extremism that were not taken seriously enough, and therefore we have put this very high on the political agenda."

Another question that now worries many Germans is just how big a threat the far right poses.

Human rights groups say more than 180 people have been killed in right-wing attacks in Germany over the last 20 years.

Neo-Nazis have murdered more people in post-war Germany than any other single group, including Islamists and the far left. But this is not yet reflected in official data.

Could it be that Germany's sensitivity to its history has made it want to play down modern-day right wing extremism?

'Tie Nazis'

"Martin", a former neo-Nazi leader who asked to be quoted anonymously for fear of revenge attacks, was an active member of the far right for 11 years. He has now left the movement and encourages others to do so through an organisation called Exit.

Martin told us the revelations about the Zwickau cell should have come as no surprise to the authorities:

"The militant scene has always said we need people who are willing and able and trained in case it comes to civil war, and neo-Nazi propaganda always talks about civil war. The scene is armed. It's military.

"Weapons training is carried out in secret. In the Arab world, for example, with freedom movements there. The right-wing scene sees itself as a freedom movement."

There is a growing collection of secretive far-right groups in Germany which call themselves the "Free Forces".

Intelligence services say this is the fastest-spreading section of Germany's far-right movement.

They say the cliche of the neo-Nazi being a boot-wearing, young, unemployed male skinhead is out of date. Nowadays you cannot always tell who is a neo-Nazi and who is not.

The Free Forces are attracting a new crowd, including students and middle-class professionals. Germans speak of a new generation of Kravattennazis, literally "Tie Nazis", as opposed to the traditional Stiefelnazis, or "Boot Nazis".

They use modern forms of protest and are harnessing social media.

Flash protests

Take The Immortals, for example - anti-globalisation, anti-capitalist and anti-democratic, they warn of the impending extinction of the German people and call for a Germany for the Germans.

Hard for the authorities to catch, they use text messaging to organise spontaneous night-time demonstrations across the country, especially in university towns.

The protesters wear black cloaks and white masks, reminiscent of the hacker-anarchists Anonymous, to hide their identity. After 15 minutes on the street, they are gone.

The Immortals use social media to stage flash protests calling for a Germany for the Germans

"The leadership is always trying to attract members of the so-called upper classes and students who, one day, can act as lawyers or doctors for the far right," Martin explained.

"It's all done very quietly, out of the public eye. You would never imagine that some of those people would support the movement and they may deny their affiliation in public, but they are very much part of the scene."

"You can't describe the far right as a fringe group any more. All parts of German society are found in it."

But what exactly do they want?

Far-right activists are camera-shy. They say they are hounded by police and hemmed in by post-war German laws which make it illegal to question the Holocaust and demonstrate public appreciation of Nazi Germany, leading to a number of far-right groups being shut down and their members prosecuted.

'Liberated zones'

We visited Berlin's best-known neo-Nazi pub, The Executioner, to see if we could tempt the punters there to talk.

Most people in the dimly lit, windowless establishment eyed us with suspicion and distaste, but after a couple of "Himla'' cocktails, Uwe Dreisch, the former head of a now-banned neo-Nazi group, sat down with us and said:

Some say sensitivity to the past has made Germans play down right-wing extremism today

"Who are we? We are nationalists. We care deeply about our fatherland. We don't like the state that exists here right now in Germany. We want to rebuild our country for our citizens, the German people.

"We want to protect our culture, our country, our religion. In Britain, you're also proud of your country, but here I, as a German, am a second-class citizen. This is because we live with eternal war guilt here in Germany. Others get preferential treatment, not us Germans.

"Those outside here who say this pub is full of evil Nazis, how would they know? They're afraid to talk to us. They just try to ban us."

What many lawmakers in Germany say they do not like is that the far right rejects the German constitution and the Federal German Republic.

Supporters of the far right want a new order in Germany, but while they live under the current system, some are establishing what they call "national liberated zones", dotted across the country.

The most famous example is Jamel, a village in northern Germany which has been largely taken over by the far right.

In the middle of the village is a brightly painted Nazi-style mural in which a traditionally dressed German mother cradles her baby, surrounded by her other children.

Also painted there is a proclamation that Jamel is free, social and national.

Birth-rate campaign

We spoke to Udo Pastoers, number two in the NPD, the legal political wing of the far right, and the leader of the party's elected representatives in the regional parliament of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the area in which Jamel sits.

Mr Pastoers was keen to discuss the NPD's current campaign calling for more indigenous Germans to have children.

The murals in the town of Jamel hark back to the Nazi propaganda of the early 20th Century

He showed me a campaign poster emblazoned with the phrase "German children need our country. Stop the German people dying out" in which two beautiful blonde parents frolic at a sandy water's edge with their blonde and beaming children.

Mr Pastoers said the birth-rate in Germany was far too low and that women should "reproduce" more, so that Germany could still deserve the name Germany.

"Imagine a country called Germany that is filled only with Africans, Arabs, Asians. Biology is our priority," he said.

The NPD does not do very well in the polls. Still, it has elected representatives in two of out of Germany's 16 regional parliaments.

Mr Pastoers told us the party was virtually gagged by the German authorities. If they really could speak openly, he said, a huge chunk of the German electorate would support them.

The NPD insists the stigma of being associated with the far right in modern Germany means that people who would like to vote for it do not dare to.

New message

In an attempt to boost its numbers, the party is currently concentrating on social issues, taking advantage of widespread unease caused by the global economic crisis.

They and the wider far-right movement run youth centres and football clubs, and offer welfare advice and family outings for those short of cash.

Former neo-Nazi Martin, who spoke of close links between the NPD and extremist groups like the one he used to lead, said the party's social card was insincere.

"They can't win over all parts of society with anti-Semitic and Nazi rhetoric. The welfare debate touches most people these days, but it is fake.

"One well-known neo-Nazi activist said: 'We'll make sure to be where people are suffering most, where they are shouting for help... Eventually we'll have them where we want them.'''

Germany's far right is a minority movement but one the country's authorities cannot afford to ignore.

- Published18 January 2012

- Published9 December 2011

- Published18 November 2011