Synthetic drug fentanyl causes overdose boom in Estonia

- Published

Everyone knows someone who has died. In the circles of Estonian friends who use "china white", death is a constant possibility.

They know that. But that does not mean they can stop.

"It's so addictive," says Marko, who has lost two friends to overdoses, and survived two himself.

In Estonia, the drug - whose proper name is fentanyl - is taking a heavy toll of young people. Nationally, drug overdoses now kill more people than road accidents.

Marko believes his only hope is to leave Estonia for good

Fentanyl, externalis a synthetic form of heroin, produced in clandestine laboratories across the border in Russia. It has almost completely replaced heroin on the Estonian market, and is much more deadly.

Feeling trapped

Marko desperately wants to break his addiction. He started injecting seven years ago, aged 18.

"I was young and stupid. I tried it with my friends when I was drunk and began to like it, and soon I was doing it every day," he says.

He has managed to cut down, and is currently shooting up three or four times a month. But he needs a daily dose of methadone to cope with the withdrawal symptoms.

And the mental dependence is much harder to deal with.

"I was away from Estonia for one-and-a-half years and didn't do drugs. But when I came back, within the first hour, I felt the temptation again - it's in my head somewhere and I can't get it out."

"I thought I will only try it for one time - I just wanted to feel it once more. But there's no such thing as one more time."

Back among his drug-taking peers, he dreams of escape.

"I have to get away from Estonia again. That's the only solution."

Survival 'miracle'

Fentanyl first appeared in Estonia about 10 years ago, during a heroin shortage.

At an addiction treatment centre in the capital, Tallinn, another addict, Ragnar, explains why it has got such a grip.

It can be hundreds of times more potent than heroin and, once sampled, there is no going back.

"People who are used to china white don't feel heroin any more. [Heroin] doesn't give any effect after china white. I found it meaningless," Ragnar says.

He has good reason to want to break his habit.

"I have overdosed about fifty times," he says.

"I don't know which kind of miracle this is. Every time I overdosed I am dead. But the emergency services came and saved my life."

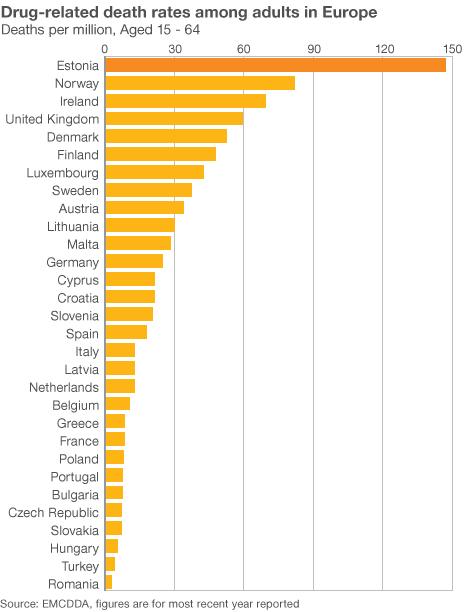

According tothe most recent data, external, Estonia's overdose mortality rate is the highest in the European Union - seven times the average.

At the Estonian Forensic Science Institute, it becomes clear why fentanyl can be so deadly.

In a small dish is less than half a teaspoon of the caramel-coloured powder.

"[It looks] like one dose of amphetamine. It's actually 37 doses of fentanyl," says police Major Risto Kasemae.

"This small amount could actually kill over 10 people, easily."

In fact, the strength of a batch can vary significantly. And when dealers cut the drug with other substances to reduce its strength, mistakes can have fatal consequences.

"They use their basic knowledge of chemistry and try their best, because actually no dealer wants their clients to be dead - but it happens quite often that it does kill people,"

"So it's really tricky to fix a dose which gets a person high, but doesn't kill."

Family dependence

Besides the rising body count, fentanyl has many other social costs. It is linked to theft and petty crime, family breakdown, and Estonia's extremely high rates of HIV and hepatitis.

"It's huge what effect addiction has had on our society," says Kristina Joost, who sees the damage first hand. She runs a needle exchange in Tallinn, where users can get clean equipment to cut down the risk of passing on infectious diseases.

"We're seeing a third generation of families dependent on some kind of substance. Now it's fentanyl, two generations ago it was alcohol," she says.

Experts in Tallinn cannot explain why fentanyl is largely restricted to Estonia

"That's the horrific truth, that drug dependent people also have families, and they become co-dependent."

Katri Abel-Ollo, an analyst for the Estonian Drug Monitoring Centre, says the Estonian government still has "no specific strategy" for dealing with the overdose issue.

She advocates training drug users in how to recognise and respond to an overdose. And allowing them to keep the overdose antidote, naloxone, at home.

Europe 'should prepare'

The big question - that none of the experts in Tallinn can really answer - is why fentanyl has taken such a hold in Estonia, but not elsewhere. And whether it is only a matter of time before it does.

"Our neighbour is Russia, that's why it came here so fast," says Ms Abel-Ollo.

But why, 10 years on, the vast majority of Estonia's users are still from its ethnic Russian community, is harder to explain. Most of the theories are anecdotal.

"Stories say Estonians prefer to sniff or take drug orally; Russians like to inject," says Ms Abel-Ollo.

"The feedback is that Russian speakers prefer heavy drugs," ventures Ms Joost.

Despite attempts to smuggle fentanyl to Finland and Latvia, and unrelated outbreaks in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, it remains, for now, mainly an Estonian problem.

But there is a warning from Katri Abel-Ollo, who has closely observed fentanyl's rise. She says the rest of Europe cannot afford to be unprepared.

"It's so lethal," she says. "I think they should be ready."