Workers in Jerez struggle without pay in indebted Spain

- Published

Bus drivers stage a daily march outside Jerez city hall, joined by social workers

Jerez may be famous for the wine that shares its name (sherry in English), but it is also developing a reputation for holding one of the biggest debts of any Spanish town or city.

On the eve of the Spanish government's budget in which deep spending cuts are expected, much of Spain has come to a standstill in protest at the government's planned labour reforms.

In Jerez, many public sector workers have not been paid for nearly four months, because of the city's stack of unpaid bills. Spain's regional debt is part of the story behind the national economic crisis that has prompted Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy's austerity drive.

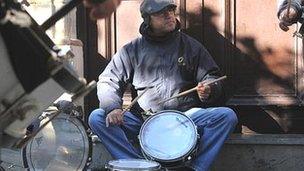

In the city's historic centre, the sound of drums can be heard most mornings these days.

A group of bus drivers start their drumming at City Hall, before marching off, escorted by police motorbikes that sporadically halt the traffic to allow the protesters to pass. The bus drivers are joined on the demonstration by some of the Jerez's social workers.

Both public professions have not been paid by their local government for nearly four months.

Boom and bust

Only the capital, Madrid, owes more money to private contractors than Jerez. Situated in the southern region of Andalucia, Jerez has a population of just over 200,000 and unpaid bills dating back to the 1990s. Its total debt stands at 959m euros (£800m; $1.27bn).

Prior to 2008, when Spain's construction boom went bust, officials in Jerez spent well beyond their means. But the politicians who racked up the majority of the debt have been voted out of power.

Following local elections last year, Jerez is now controlled by Spain's centre-right Popular Party (PP).

For several decades, up until the end of the 1990s, a regional Andalucian nationalist party was in power.

'Asking to be paid'

Antonio protests during the mornings then works his shift later in the day

Antonio Dominguez has driven the city's buses for much of his life. However, for the past four months he hasn't been paid.

He's a father of three, and says he now cannot afford his children's books for school, so he makes photocopies instead.

"We are just asking to be paid for the job we have already done," he said.

For now, Antonio turns up at the regular morning protest and march, but he still works his shift in the afternoons, driving his usual bus route, which starts in the centre of the city.

Marching alongside her colleagues, social worker Encarnacion Barrios, who looks after the city's elderly, says she has not been paid on time for the past four years. She too is owed four months' pay.

"People cannot pay their mortgages and some colleagues sometimes cannot afford to feed their children," she said.

Occupy Jerez

Jerez's mainly female social workers have now set up camp outside the doors of the City Hall.

Their giant purple tent sits below a row of orange trees and alongside several cafes. Social worker Esther Dominguez says the elderly people they look after are suffering as they receive less care from the local government.

"It's a simple case of mismanagement," she complains. "But the new PP government said they would sort things out, and so far we've seen no solutions."

When the Popular Party took charge in Jerez last year, they called in external auditors to establish the extent of the financial problems.

The mayor, Maria Jose Garcia-Pelayo, said the audit confirmed a "dreadful negative economic situation". However she announced a programme of cuts, wiping 25m euros off the city's total annual public spending.

Jerez has cut its annual spending by 25m euros, reducing public sector salaries

Her plan will cut the government's political infrastructure by 40% and reduce the salaries of some public sector workers by 30%.

Mrs Garcia-Pelayo said her Government was "tightening its belt" and would get rid of its budget deficit by 2013. But many believe Spanish towns and cities like Jerez will have to receive some kind of financial support from the central government.

Javier Diaz Gimenez, from Spain's IESE business school, believes some of the country's indebted municipalities will either have to be granted "privileged loans, with guarantees from the state, or direct bailouts from the state".

Knock-on effect

The Spanish government has already set out a plan for low interest long-term loans for local governments with big debts.

Under this plan, it hopes that private companies that provide local transport, cleaning and rubbish-collection services should receive the money they are currently owed by local governments by May this year.

Javier Diaz Gimenez says many of these companies are small or medium-sized businesses.

"The total value of the unpaid bills as been quantified at around 50 billion euros, that is around 5% of Spanish GDP," he said.

"Some of these companies are in deep trouble and some are simply going bankrupt because they are not being paid by public administrations."

And if a local government is broke, then there is knock-on affect on the local economy.

Francisco, a waiter in Jerez, says takings have fallen at the cafe where he works.

"We're all in this together. If people aren't earning, we're all affected."