Sun, snow and sustainability in Zermatt

- Published

The beauty of the Matterhorn swells the Swiss municipality of Zermatt's population each year

Tourist resorts depend on attracting visitors, and no-one likes to have empty rooms; nevertheless, some of the world's most popular resorts are beginning to ask themselves whether they are simply too successful.

Switzerland's famous resort of Zermatt, home of the iconic Matterhorn, attracts almost two million visitors a year, and a million of them make the trip up to the Klein Matterhorn in order to enjoy one of the world's most spectacular views.

On a clear day, at an altitude of 3,883 metres (12,740 ft), visitors can see not only the Matterhorn itself, but across to Mont Blanc in France, and, to the south, to the hills around Milan in Italy.

The problem for Zermatt is that the visitors who make the trip up are not usually satisfied simply with the stunning view - they want hot food, cool drinks, and flushing toilets too.

Providing all that requires electricity, and, rather than run ugly power-lines up the mountain, Zermatt has been working on some innovative solutions.

The new restaurant at the Klein Matterhorn looks at first sight as if it is made simply of glass.

Lunches are partly warmed by energy absorbed from the sun at the restaurant on the Klein Matterhorn

Closer inspection reveals photovoltaic solar panels - these produce the electricity the restaurant needs to function.

The restaurant has won the European Solar Prize for its innovative design and its contribution to protecting the alpine environment.

But supplying high altitude hot meals for tourists is just one of many challenges Zermatt faces.

Population explosion

When the high season begins, Zermatt's population multiplies overnight, and the consequences of that are all too clear to the town's mayor, Christoph Burgin.

"On December 26th we go from a population of 6,000 people to 35,000 or 40,000 people in just one or two days," he explains.

"And we have over 40 four-star hotels, with all the spa facilities. You can imagine, after four o'clock, everyone is taking a shower, or washing, we need immense, really immense amounts of water."

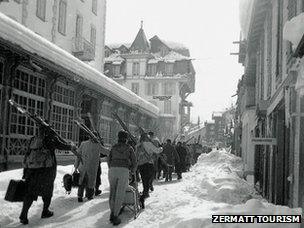

The town, and the demands tourists make of it, has changed dramatically....

Zermatt is lucky in that it has a number of natural water sources, but the huge water use means it is now having to build a new waste water treatment facility with a capacity for 65,000 people, more than ten times the town's resident population.

And the town is still expanding; hotels and apartments continue to be built to accommodate the growing number of visitors, and there are controversial proposals to build a tower on the Klein Matterhorn, a glass pyramid which would raise the mountain to over 4,000 metres in height, housing restaurants, a hotel, and conference rooms.

Zermatt's cable car company, which would benefit from even more traffic up the mountain, is keen on the idea, but Mayor Burgin is uncomfortable.

"As mayor of Zermatt it's very difficult for me to imagine a tower on the Klein Matterhorn," he says.

"Personally, I think it is not possible, we have built a restaurant up there. But a tower with a hotel? It's not good to do such things."

Investment in sustainability

There are signs that local Zermatters are beginning to agree with Mayor Burgin.

Despite the fact that many people make their money from tourism, new developments are more cautious.

Investment in greener buildings is becoming more common; Zermatt's new youth hostel was the first in Switzerland to be built according to strict minimum energy standards. It too has solar panels to provide hot water.

...and the amount of water they consume in the small town's many luxury spas has soared too

And the new upmarket Hotel Firefly, rather than rely on traditional oil-fired heating, has sunk 12 bore-holes deep into the ground, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs.

All the hotel's heating and hot water, including for its extensive spa facility, come from this geothermal source.

"We wanted to do something sustainable," explains owner Michael Kalbermatten. "I think this is the future, more hotels will be built like this."

Meanwhile, outside on Zermatt's streets, tourists will never see a car.

Private vehicles have always been forbidden, the only type permitted are electric carts belonging to the hotels, or traditional horses and carts.

Environmental 'window dressing'

But environmentalists are not entirely convinced. Eva Maria Klay, of Switzerland's Pro Natura group, calls the efforts at sustainability "window dressing".

"This, to me, is not sustainable," she says. "If you look at most of the buildings in Zermatt, they are not properly insulated, and they are all fuelled by oil."

"And they keep on building these jumbo chalets, five or six storeys high. Every year there are on average 18 new constructions. If they continue like this, in 30 years there will be no space left."

That is a concern Swiss voters share; in a referendum in March they supported a proposal to limit the number of holiday homes in Alpine resorts to a maximum of 20%. It is a law which is expected to affected building in places like Zermatt.

Time to slow down

And, although tourism has turned Zermatt from a poor and isolated Alpine village into one of the world's wealthiest resorts in under a century, even tourism officials think it is time the town slowed down.

"I think we still have luck that people like the charm of the village," says director of tourism Daniel Luggen.

"But, the more we attract the people, the more the challenge is to keep it clean and untouched. For me this is kind of like sitting on a branch and sawing on that branch, and we don't know when it's going to crack."

"If we could install a kind of maximum level (of visitors) I would actually go for that," he continues.

"But Switzerland is a free country, anyone can travel anywhere any time, so I think it would be quite a challenge to make a maximum number of visitors, or a maximum length of stay, so we really have to find other ways."

Meanwhile, Mayor Burgin is also keen that Zermatt consolidate its success, rather than try to expand further.

"I don't want Zermatt to become Disneyland," he warns. "We have to live here and the children have to grow up in a town like a town, and not only a tourist resort.

"The balance is difficult, because the people coming want to be in an area where everything is very like Disneyland… and I hate this, we are not only here for tourists, it's my life, it's my town, and it's also for my children."

- Published29 July 2011

- Published3 December 2011