Grief of Bosnia war lingers on

- Published

Allan Little recalls "the cycle of vengeance and counter vengeance"

The BBC's Allan Little recalls the horrors of the Bosnian war, 20 years after Serb forces laid siege to the capital Sarajevo.

There is a moment that returns to me again and again. An old man emerges from a wood and makes his way towards where I am standing. The lovely green valley has tipped into autumnal browns and it is a cold, damp morning.

The old man is one of 40,000 people driven from their homes in the central Bosnian town of Jajce, and they have been walking for two days to reach safety.

The Bosnian war gave to the lexicon of conflict a grotesque new euphemism: ethnic cleansing. These are its latest victims.

I asked the man how old he was. He said he was 80. May I ask you, I said, are you a Muslim or a Croat? And the answer he gave me still shames me as it echoes down the decades in my head. I am, he said, a musician.

It was a rebuke to the convenient ethnic shorthand to which we reporters reduced the lives of fully rounded, blameless and accomplished human beings.

The Western democracies misread the war. For years. It was ancient ethnic hatreds. It was all sides equally guilty. It was the Balkans. There was nothing that could be done.

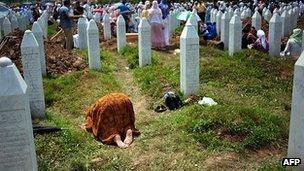

The 1995 Srebrenica massacre triggered more robust Western intervention

It wasn't so. The refugees were not fleeing fighting. For the most part there wasn't any fighting - the military imbalance was far too great in most places for that.

There was, instead, a huge military machine that went from municipality to municipality driving people from their homes. Many thousands were murdered; still more were detained in concentration camps where some were tortured or raped.

Costly delay

The war lasted 44 months. On average 100 people died every single day, for more than three and a half years. In a country the size of Scotland.

The Western democracies watched in anguished indecision until a single atrocity - Srebrenica - pushed the world to act. But Srebrenica was different only in scale from what had been happening for more than three years.

A few days after I met the musician I was drawn into the war in a personal and painful way. Someone I was working with - someone I felt responsible for - my cameraman - was killed in an incident that I survived.

He was 25, a brave and creative film maker from Zagreb. He was a funny and charming companion who hated the war but believed in the need to document it up close. After John Bunyan we called him, in jest, Mr Valiant for Truth. We collected his body and drove it over narrow mountain passes back to his native Croatia.

At his funeral we broke our hearts. I was immobilised by grief and rage, for a moment connected, viscerally, to the passions that fuelled the war - the impulse of vengeance and counter-vengeance.

War reporters love what they do and feel guilty about that. But it wears you out sometimes. You would come home from the war and be dismayed by the indifference of others. People asked about the war but their eyes would glaze over when you answered. So you would seek out others who'd been there.

Walking in Hyde Park you would instinctively avoid the grassy areas in case there were landmines. You would scan the roof tops of Oxford Street for snipers. And you couldn't wait to go back.

Get in touch with BBC Radio 4 Today programme via Twitter, external, Facebook, external or text us on 84844.

- Published7 February