Women first rule 'ignored in ship disasters' - study

- Published

Research suggests that in a crisis women are only first into lifeboats when the rule is backed up with force

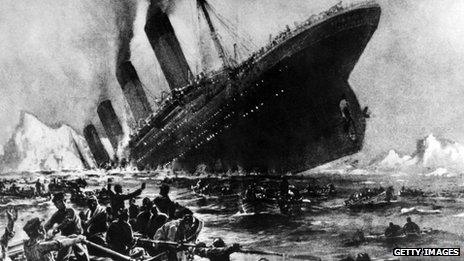

The belief that women and children are first to be saved when ships sink is largely a myth, a new study suggests.

Analysis of survivors from 18 maritime disasters shows women "have a distinct survival disadvantage", say researchers at Uppsala University in Sweden.

<link> <caption>The report</caption> <url href="http://www.nek.uu.se/Pdf/wp20128.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> says captains and crew have a significantly higher survival rate.

The Titanic disaster 100 years ago this week was a rare exception because the captain threatened to shoot those who disobeyed, they conclude.

But the "women and children first" rule is now seen as the normal way to behave in emergencies.

The authors of the report, economists Mikael Elinder and Oscar Erixson, say the captain has the power to enforce the rule.

But they say their findings show that behaviour in real life-or-death situations is best captured by the expression "every man for himself".

Improving survival rates

The study covered sea disasters spanning three centuries, involving more than 15,000 people. The authors say data from 16 of the ships had never been analysed in this way before.

The first was the troopship HMS Birkenhead on 26 February 1852, which the authors say was the disaster often seen as giving rise to the idea of saving women and children first.

The Birkenhead carried around 20 family members of officers, as well as troops. There were too few lifeboats for all on board, and when it started sinking orders were given for women and children to go first. The 191 survivors included all seven women. The death toll was 365.

When the American liner SS Arctic sank in September 1854, women and children were also ordered to the boats first. But the evacuation was disorganised, and they quickly filled with crew. The captain threatened disobedience with violence, but hesitated to enforce his orders. The death toll was 227, including all women and children, and the 41 survivors were mostly crew members.

When the MS Estonia started sinking in the Baltic in 1994, it listed sharply, causing panic on board. It became difficult to launch lifeboats, and most of the 852 who died were trapped inside the ship. There was no record of a "women and children first" order being given and the evacuation was not orderly, said the report. There were 137 survivors.

The analysis showed that the gender gap in death rates has narrowed in disasters since World War I. The authors say this is connected with women's generally higher status in modern society.

They also point out that in more recent disasters people show altruism to more vulnerable people generally, such as those with disabilities.

The study suggests that women are generally at greater disadvantage in British shipwrecks, and the length of time the disaster takes to unfold has no bearing on whether more efforts are made to save women and children.

- Published16 January 2012