What next for Marine Le Pen's National Front?

- Published

The success of the far-right National Front (FN) in France's presidential election is both new and not new; and it is important to analyse precisely its political and social implications.

What is not new - at least not remarkably so - is the size of Marine Le Pen's vote.

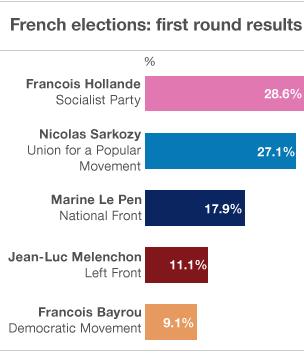

Ms Le Pen polled 6.4 million votes in Sunday's first round, or 17.9% of the total. In 2002 her father Jean-Marie got 16.86% of the vote: 4.8 million overall.

But to make a proper comparison, one should add to that the score of the other far-right candidate in 2002 Bruno Megret, who got 660,000 (2.3%).

Plus there was a hunters' rights candidate in 2002 - who had a whopping 1.2 million voters, many if not most of whom would otherwise have chosen the FN. So, a total (if you count the hunters) of 6.6 million.

The point is not to play down Marine Le Pen's success -- but to show that the FN has been around for a long time, and has had previous moments of glory.

Same message

According to Sylvain Crepon, a sociologist who specialises in the French far right, the fundamentals of the FN demographic have not changed that much.

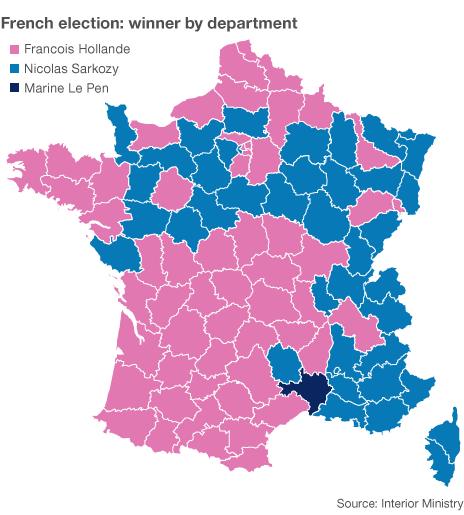

"The broad lines haven't moved since the 90s. It is a vote that has taken root east of a line from Le Havre in the north to Perpignan in the south, and is made up of the victims of globalisation," he says.

"It is the small shopkeepers who are going under because of the economic crisis and competition from the out-of-town hypermarkets; it is low-paid workers from the private sector; the unemployed.

"The FN scores well among people living in poverty, who have a real fear about how to make ends meet."

One other thing that did not change this year was the message.

Certainly, Marine Le Pen spent the early part of her campaign focusing on economic issues and Europe.

But in the last weeks there was a noticeable change of tack, after polls showed her vote beginning to tail off. Reverting to her father's classic themes of immigration and law-and-order, she saw an immediate pick-up in support.

Rural vote

So on one level, Marine Le Pen's 2012 triumph follows logically from what went before.

But of course on another level things are different. Largely because France itself is different.

Many people have commented on the fact that the far-right vote appears to have grown in rural areas. In the past it used to be focused around industrial blight-spots and high-immigration cities in the south and east. But now it has spread.

But "rural" areas today does not mean villages full of farmers. It means small provincial towns, and the new housing-estate commuter belts being built on the distant outskirts of the cities.

"The rural underclass is no longer agricultural. It is people who have fled the big cities and the inner suburbs because they can no longer afford to live there," says Mr Crepon.

"Many of these people will have had recent experience of living in the banlieues (high immigration suburbs) - and have had contact with the problems of insecurity."

In this semi-urbanised countryside, people feel the hopelessness of a life in poverty uncompensated-for by the traditions and structures that would have made it bearable in the past.

Shops are now in vast out-of-town zones; no-one goes to church; work is a 50-kilometre drive away. And the cost of the two staples - cigarettes and petrol - has just shot through the roof.

For these people, an FN vote offers both a protest (against the wealthy; against the EU; against the establishment), but also a claim: for an identity and the right to a traditional "French" way of life.

Le Pen's new generation

Commentators have been struck by other changes in the FN vote this time.

There are more young people. According to pre-vote polls, 25 % of 18-24 year-olds were planning to vote for Marine Le Pen. The given explanation is that young people are increasingly pessimistic, and see little hope in the mainstream political argument.

Another difference is that more women are voting for the party. In the past, there was a distinct macho element which put off women. But thanks to Ms Le Pen, this has dissipated.

Indeed more broadly, Marine Le Pen has given the FN the face for a new generation.

It is not just that she has broken with the sinister relics of the old guard, with its roots in anti-Semitic Vichy. She is also very identifiably a modern French woman.

With her two divorces, steely femininity, and cigarette-roughened voice, she comes across as far more "normal" than most of her political rivals.

Political shift

But perhaps the most important change is one in the overall social context.

Across Europe, political parties are emerging that are variously described as "populist", "far-right", "anti-immigration" or "new right".

"In all our societies there is this populist push," says political scientist Dominique Reynie. "And the whole of the body politic is shifting to the right."

This has been accompanied in France by an increased willingness in the media to challenge received ideas about the far right, and to talk a little more openly about issues such as immigration.

Some see this process as a worrying change, because it "legitimises" the themes of the far right.

Indeed President Sarkozy himself is regularly blamed for helping the growth of the National Front, by deliberately targeting its voters (as he is doing now, ahead of the 6 May second round of the election).

But the success of "politically incorrect" social commentators such as Eric Zemmour, whose books sell in the hundreds of thousands, shows there is an appetite for a new language about subjects like Islam and national identity.

So Marine Le Pen is drawing on her father's legacy, but at the same time moving with the times. The question is what she can do with this success.

'Decontamination'

Her interest is quite clear. She would like Nicolas Sarkozy to lose the presidential election, and for this to trigger a breakdown in the structures of the political right.

She would then re-launch the National Front under a new name and, after picking up right-wing defectors from Sarkozy's UMP, set herself up as the main opposition to the Socialists.

The key moment in this strategy will be the legislative elections in June, where she is hoping to win enough seats to form a parliamentary group.

Till now electoral rules have made it almost impossible for the FN to win seats in the National Assembly, despite its strong national showing. But this could change if the FN vote in key constituencies continues to rise. And above all if, against all precedent, local deals begin to be struck with the mainstream right.

That would be the logical next step in the "decontamination" of the FN brand, with the party then becoming a Nordic-style far-right party that is an accepted part of the political spectrum.

It may come to that. But it may not either.

In the past, the Front National's moments of glory have too often melted into oblivion. A few months after Jean-Marie Le Pen's 2002 triumph, it was just a scary folk-tale for the left. Nothing had actually changed.

This time, thanks to Marine and the changing context, things do feel different. But we need to wait for "la suite".