Real-world beaming: The risk of avatar and robot crime

- Published

A demonstration of how robot 'beaming' technology works

First it was the telephone, then web cameras and Skype, now remote "presence" is about to take another big step forward - raising some urgent legal and ethical questions.

"Beam me up Scotty" - that simple phrase reminds us of Captain Kirk, whisked from alien worlds back to the Starship Enterprise via the magic of "teleporting", in the cult TV series Star Trek.

Beaming, of a kind, is no longer pure science fiction. It is the name of an international project funded by the European Commission to investigate how a person can visit a remote location via the internet and feel fully immersed in the new environment.

The visitor may be embodied as an avatar or a robot, interacting with real people.

Motion capture technology - such as the Microsoft Kinect games console - robots, 3D glasses and special haptic suits with body sensors can all be used to create a rich, realistic experience, that reproduces that holy grail - "presence".

The kit is getting cheaper all the time and researchers expect that in the near future it will be quite easy to set up a beaming-enabled room in a typical home. Beaming may also use less bandwidth than conventional video streaming.

Project leader Mel Slater, professor of virtual environments at University College London (UCL), calls beaming augmented reality, rather than virtual reality. In beaming - unlike the virtual worlds of computer games and the Second Life website - the robot or avatar interacts with real people in a real place.

He and his team have beamed people from Barcelona to London, embodying them either as a robot, or as an avatar in a specially equipped "cave". One avatar was able to rehearse a play with a real actor, the stage being represented by the cave's walls - screens projecting 3D images.

The technology is already good enough for "blocking" a play - working out how the actors should move around the stage - though emotion and facial expressions are not yet captured accurately enough to replace a traditional rehearsal. This may not be far off, however.

Teleconferencing would be transformed, once beaming is able to convey the non-verbal communication that people value, reducing the need for businessmen to jet around the world.

The cinema experience could also be "augmented".

In Aldous Huxley's science fiction classic Brave New World characters enjoy the "feelies" - films that thrill with sensations of touch and smell as well as sound and vision. Beaming might one day deliver something comparable. And imagine what erotic movies could do with that.

There are many other areas where the technology has obvious applications.

Beaming sessions could help military morale by giving soldiers based overseas a sense of being back home with their loved ones. The same would apply to workers or businessmen posted abroad.

A virtual doctor could visit a patient at home, if that patient is unable to travel to the surgery.

Surgeons can already perform operations via telemedicine and beaming might not only make that routine but also enable medical students in different countries to get hands-on training simultaneously.

But this also raises the possibility of new types of crime.

Could beaming increase the risk of sexual harassment or even virtual rape? That is one of many ethical questions that the beaming project is considering, along with the technical challenges.

Law researcher Ray Purdy says you might get a new type of cyber crime, where lovers have consensual sexual contact via beaming and a hacker hijacks the man's avatar to have virtual sex with the woman.

It raises all sorts of problems that courts and lawmakers may need to resolve. How could a court prove that that amounted to molestation or rape? The human who hacks into an avatar could easily live in another country, under different laws.

The electronic evidence might be insufficient for prosecution. Crimes taking place remotely might sometimes leave digital trails, but they do not leave forensic evidence, which is often vital to secure rape convictions, Purdy says.

"Clearly, laws might have to adapt to the fact that certain crimes can be committed at a distance, via the use of beamed technologies," he says.

Sexual penetration by a robot part is another possibility. Current law may not go far enough to cover that, Purdy says. And what if a robot injured you with an over-zealous handshake? Or if an avatar made a sexually explicit gesture amounting to sexual harassment?

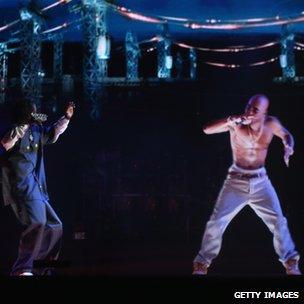

A performing 3D image of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur (right) amazed fans in California last month

The law, as it stands, does not make explicit who would to be blame, but the accused in such a case would have to be the person controlling the virtual visitor, Purdy says - the person who is embodied as a robot or avatar - as the law can only prosecute humans.

He argues that using a robot maliciously would be similar in law to using a gun - responsibility lies with the controller. "While it is the gun that fires the bullet, it is the person in control of the gun that commits the act - not the gun itself."

The use of lifelike avatars would also open up the possibility of a range of new forms of deception.

In the same way that some paedophiles masquerade as adolescents in internet chatrooms you could also have impostor avatars.

Some users of internet dating sites lie about their age or other personal details. So how could you be certain that an avatar accurately represents a real person, on a dating site, say, or at a business meeting via teleconference?

"When we visually see real-life humans we can make presumptions and choices that might not be available through beamed augmented reality interactions," Purdy says.

A related issue is identity theft. You can copyright a person's creative output, but in future you might need to copyright the actual person.

Recently hip-hop fans in California were stunned when the late Tupac Shakur was reincarnated using a projector, a mirror and a mylar screen, and this reincarnation performed alongside rappers Dr Dre and Snoop Dogg. At least the virtual Tupac, who some likened to a ghost of the rapper gunned down in Las Vegas in 1996, did have the bereaved mother's blessing.

The Kinect technology, capturing an individual's gestures, is potentially a powerful tool in the hands of an identity thief, argues Prof Jeremy Bailenson, founder of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University, California.

"A hacker can steal my very essence, really capture all of my nuances, then build a competing avatar, a copy of me," he told the BBC. "The courts haven't even begun to think about that."

Non-verbal behaviour, like the way you walk, is more revealing about you than what you decide to put on Facebook, he said. It is like the difference between biometric data and a standard photo.

Everyone would prefer to have a good-looking avatar

However, the rich "digital footprint" that people leave on the internet can also help to identify cyber criminals.

A cyber bully hiding behind an avatar often leaves more evidence than someone bullying face-to-face, says Bailenson, author of Infinite Reality.

People may wish to have different avatars for different purposes. A businessperson, for example, may wish to appear differently to clients in various parts of the world. And given a free choice, most people will pick an avatar that looks better than they do in reality.

This is very obvious from Second Life, but Rod Humble, chief executive of Second Life's creator Linden Lab, says it is just like early classical art that focused on idealised forms - realism came along much later.

Like some others, he has noted a trend for avatars to more closely resemble their owners.

Prof Patrick Haggard, a neuroscientist at UCL who has been examining ethical issues thrown up by beaming, says there is a risk that such a virtual culture could reinforce body image prejudices.

But equally an avatar could form part of a therapy, he says, for example to show an obese person how he or she might look after losing weight.

As beaming develops, one of the biggest questions for philosophers may be defining where a person actually is - just as it is key for lawyers to determine in which jurisdiction an avatar's crime is committed.

Even now people are often physically in one place but immersed in a virtual world online.

Avatars challenge the human bond between identity and a physical body.

"My body may be here in London but my life may be in a virtual apartment in New York," says Haggard. "So where am I really?"