Irish Republic nervous about Euro treaty referendum

- Published

'When it comes to rejecting European treaties, Ireland has a long track record'

With three weeks to go until Ireland's referendum on the latest European Union treaty, a degree of nervousness is discovered inside the Irish government.

A large poster urging a 'yes vote' slipped off the wall and crashed onto the floor just as an Irish government minister was about to launch his pro-treaty campaign.

As the 'yes' placard shook, wobbled then fell, a voice at the back of the room shouted: "That may be an omen."

Quick as a flash, Minister Ruairi Quinn responded: "That's exactly why we need a new treaty - we need stability."

There was a nervous laugh in the room. Although the 'yes' camp is leading in the polls, there is a danger of a last-minute slide in favour of the anti-treaty campaign before the 31 May vote.

In the last opinion poll, 10 days ago, the results were:

47% yes

35% no

18% undecided

When it comes to rejecting European treaties, Ireland has a long track record.

Both the Nice Treaty (2001) and Lisbon Treaty (2008) referendums were lost, forcing the governments of the day into the embarrassing position of having to re-run the votes to get them passed.

Having learned the lessons of past failures, complacency should not be a problem this time. Or will it?

Relatively tame

Even with just three weeks to go, the campaign seems stuck in second gear. The debate has not caught fire.

By Irish standards, the exchanges in the Dublin parliament have been relatively tame.

However, this is not just a reflection on the 'yes' camp but also on the 'no' camp.

One reason for the lack of political fireworks, is that the treaty is so complicated. It does not easily lend itself to the art of the soundbite.

Even the title is a mouthful - The Treaty on Stability, Co-ordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union.

It doesn't exactly roll off the tongue.

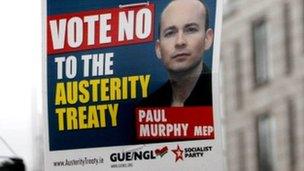

Supporters call it The Stability Treaty, opponents brand it The Austerity Treaty.

Whatever title you give it, the document is full of fiscal jargon.

The big danger facing the Irish government is that many voters will abide by the old political maxim: "If you don't know, vote no".

The treaty was drawn up in response to the euro-zone debt crisis.

Ireland was at the heart of the crisis. Its fiscal collapse in 2010 meant the country, once the envy of the world with its Celtic Tiger economy, suddenly needed an EU-International Monetary Fund bail-out.

Scupper treaty

The new treaty forces countries to enshrine in national law a so-called 'golden rule' to balance budgets or face automatic sanctions. The aim is to strengthen fiscal discipline and toughen the enforcement of EU budget rules.

The new measures come into effect once 12 EU states have ratified the treaty. Unlike Lisbon and Nice, an Irish 'no' does not scupper the entire treaty.

The upshot is that Ireland has no excuse for a referendum re-run if it does not like the verdict of the people.

Given that the three largest parties in the Irish parliament - Fine Gael, Labour and Fianna Fail - support the treaty, logic suggests it will be passed.

However, many Irish people have been left angry or jobless in the wake of the economic crash and a long series of hard-hitting budgets.

They are fed up with austerity, and the main argument from groups opposed to the treaty is that it will simply lead to more of the same.

The fear is that governments will have to keep cutting pay and services to stay within EU budget limits.

Leading the charge against the treaty is Sinn Fein, and opinion polls suggest the party's popularity in Ireland is rising faster than any other.

Sinn Fein's deputy leader Mary Lou McDonald said: "The recent election results in France and Greece are a massive blow against the failed policies of austerity in Ireland and across Europe.

"A 'no' vote in Ireland on 31 May will strengthen the hand of all those arguing for jobs and growth."

Pro-treaty campaigners argue the opposite. The Irish prime minister Enda Kenny has dismissed Sinn Fein's "fantasy economics".

The yes campaign say that voting 'no' would be economically perilous, as Ireland would lose access to the permanent rescue fund, The European Stability Mechanism.

The Labour leader Eamon Gilmore, who is Ireland's deputy prime minister, claims a vote for the treaty is a vote for economic recovery.

Speaking at the launch of his party's referendum campaign, he said: "Yes, people are very angry in many cases about some of the decisions that, as a government, we've had to make.

"People are drawing a distinction between individual decisions that the government has had to make, and what is the right and common sense thing to do in order to ensure that we have a stable currency, confidence from investors and that we'll have access to emergency funding."

It was just before he rose to speak that the 'yes' poster fell down. There was just enough time to stick it back up again.

However, after Ireland goes to the polls on 31 May, there will be no second chances or referendum re-runs.

Whatever decision the Irish people make, the government will be stuck with it.