Germany's Pirate Party riding high

- Published

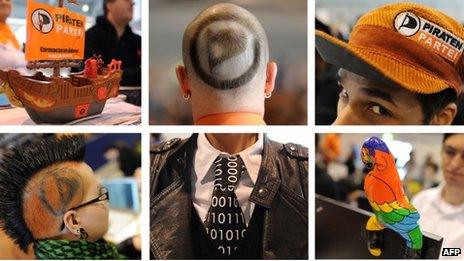

The German Pirate Party's national conference was a riot of colour and noise

All across Europe, disgruntled voters are deserting the established parties, and in Germany, it is the Pirate Party they are turning to.

At regional elections at the end of April, they got 8% of the vote, enough to give them seats in the state parliament of Schleswig-Holstein, in the far north of Germany. It is the third state in which they now have people in parliament, making law. In Berlin, they have 15 members of the legislature.

This weekend, they may well do the same in the elections in North Rhine-Westphalia, the German state which is as big as many European countries and includes Cologne, Duesseldorf and the Ruhr conurbation.

But it is an unconventional party like no other. Their recent conference was a riot of colour and noise. Some members were dressed as pirates, complete with three-cornered hats. Others played in a children's pool filled with plastic balls, diving in and bursting out from under the surface.

Granted, there were formal speeches from the platform, but the hall was filled with people glued to their laptops on lines of trestle tables. They seemed to participate in the conference with one ear listening to the real world, but two eyes staring into cyberspace, their brains flitting in between the two.

They are unconventional in another way, too. They do not have the usual range of policies on all the usual - and important - issues, like the detail of tax rates or how to save the euro. But the unconventional approach is working.

One of their leaders, Matthias Schrade, told the BBC that the appeal of the Pirates lay in the fact that they were trying to get back power from politicians and give it to ordinary people.

"We offer what people want. People are really angry at all the other parties because they don't do what politicians should do. We offer transparency, we offer participation. We offer basic democracy."

'Liquid Democracy'

Their method of policy-making illustrates their unconventional approach to policy-making. They call it "Liquid Democracy" and it involves members making suggestions online which then get bounced around through chat rooms, which they call Pirate Pads, before emerging from cyberspace into the real world as policy.

Polls suggest that the biggest support for the Pirates <link> <caption>is among those aged under 34</caption> <url href="http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/bild-829451-343887.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> . The party has taken votes from the Left Party and the Greens, but it has also drawn in new voters.

So as national elections loom in 2013, other parties are trying to work out what to make of them. In a country which rules by coalition, small parties have the power to decide who forms the government. Can the party of the moment be a party of the future?

Laptops are a ubiquitous sight at party gatherings

One of the difficulties is that the very essence of the Pirate Party is informality.

The Pirate Party as a movement started in Sweden in early 2006, with others, including the German Pirate Party, soon following. The name stems from the argument over intellectual property on the web.

Owners of intellectual property, like music publishers, argue that those who just download their material without paying are "pirates", so the name stuck to those who argued for more freedom to source material on the internet, as the pirate parties invariably do.

In Sweden, there are two Pirate Party MEPs. In Germany, the party has no members in the national parliament, the Bundestag, but it is sweeping forward into state legislatures.

In Berlin, for example, they espouse policies usually associated with both the left - like a guaranteed income for all - and with the right - like antipathy towards government regulation of the internet.

Libertarian instincts

They have libertarian, democratic instincts which can sit on the right of politics or the left.

The big question is whether their regional success will translate into national success when the federal government is up for grabs next year.

Broadly, national opinion polls have the Christian Democrats of Chancellor Angela Merkel bumping along at around 36%. The main opposition party, the Social Democrats, receives just 26%. In other words, both need an alliance.

But support for the pro-business Free Democrats, currently in government with Ms Merkel, has been collapsing.

So, who might fill the gap? In the past, it has been the Greens, but they are now neck-and-neck with the Pirates. Accordingly, the Pirates could make or break a government.

It is the Left Party which is the most vulnerable to their rise, according to political scientist Gero Neugebauer of the Free University in Berlin:"That means it's becoming harder for the Social Democrats and the Greens to get a majority in 2013."

He says their lack of policy so far has been an asset because they say policy comes from the bottom, not the top. "That's the trick. They say 'we don't know, you don't know - so we'll find the answer together'."

"The reason for their quick growth is that they are new and that's enough at the moment. But not in the long run."

But in the short run, the Pirates are riding a wave of disgruntlement. And disgruntlement does not look like it is going out of fashion any time soon. It may still be here to sweep the Pirates into the Bundestag next year.

- Published25 March 2012

- Published7 May 2012

- Published18 September 2011