Ukrainians polarised over language law

- Published

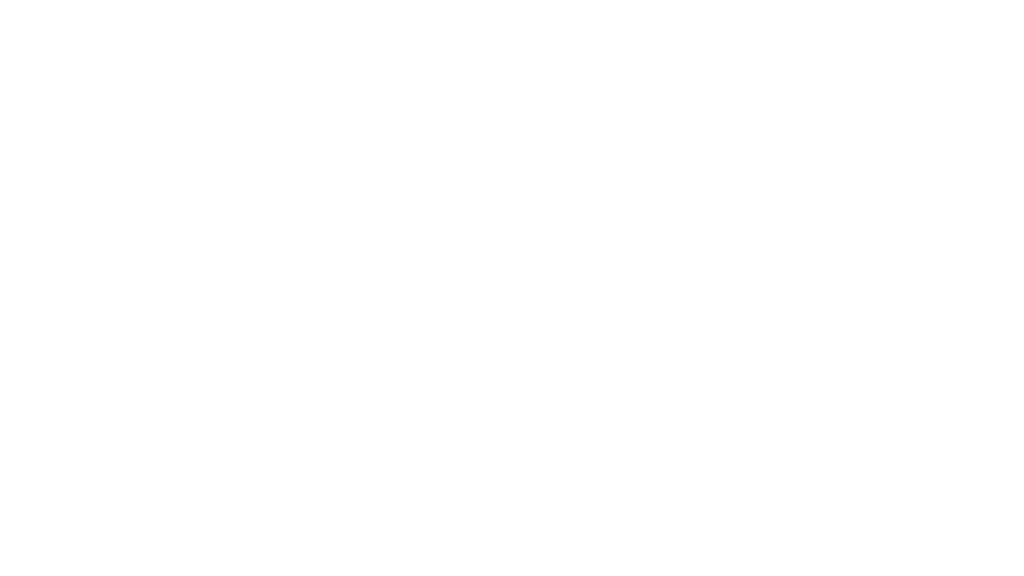

The move to boost the status of the Russian language sparked violent protests

On Wednesday, just days after the country celebrated the final whistle of the European football championships, Ukraine once again demonstrated its position as one of the former Soviet Union's more turbulent political cultures.

Nearly 1,000 demonstrators clashed with scores of black-helmeted riot police in the capital Kiev, with both sides using pepper spray and law enforcement officials wielding batons to disperse the crowds.

The protesters had gathered on the previous day, after the country's parliament unexpectedly passed a controversial law that granted official status to the Russian language in regions where it is predominantly spoken.

Language is a contentious issue in Ukraine. Many here view the use of the Ukrainian language as central to the country's identity.

They believe that - after centuries of Russian and Soviet hegemony - to be a true Ukrainian, one must speak Ukrainian.

Anything less is to surrender to the country's one-time cultural and political masters in Moscow - where many still view Ukraine as a Russian appendage - and ultimately threatens the country's continued independence.

Eyes on elections?

"This law is sending an incredibly powerful signal that the Ukrainian language is not needed," said Roman Tsupryk, a political commentator and chairman of the editorial board of the Ukrainian weekly "Tyzhden" (Week).

"People don't see the mechanism behind it, but they will see the consequences in a year or a year and half."

People in the country's Russian-speaking east and south have a predictably different view on the matter.

They say that they are patriotic Ukrainians - just ones that speak another language - and they simply wish to have the right to speak their native tongue in courts, government offices and schools, as the new legislation stipulates.

They also bristle at the accusation - especially in the country's west, where Ukrainian is predominantly spoken - that they are any less Ukrainian than the rest of the country.

"I speak Russian - what's the big problem?" said Ruslan, a taxi driver in the eastern city of Donetsk, who asked to use only his first name.

"Why do people in the west get to say who is Ukrainian and who isn't?"

Given the intense emotions on either side of the language debate, however, the question arises why President Viktor Yanukovych's ruling Party of Regions chose this moment to stir up this particular hornet's nest?

Some analysts believe the new language law is an opening salvo in the government's campaign for parliamentary elections in October.

The law, touching on a cultural hot button, they say, serves a dual purpose - it distracts the electorate from more pressing issues like Ukraine's continued economic slump, and it riles up the political "base."

'Space for radicals'

"Every time we have elections, the issue of language is there," said Oleh Rybachuk, a cabinet member in the previous government and now an independent analyst.

"Language is not so important - it is not among the top 15 priorities of the people. But for some reason, every time we have elections, we have that issue."

According to Mr Rybachuk, however, opposition politicians also welcome this issue, since it allows them to mobilise their own constituency. But this could have disastrous consequences.

"This kind of cementing of constituencies really divides the country," he says, adding that the unrest "creates space for radicals from both side."

"It's easy to provoke a conflict, to shed blood," he adds.

The bill still requires the signatures of the speaker of parliament and president to pass into law

Granted, not all of Ukraine is divided into two opposing camps - and it remains to be seen how this pro and anti-Russian stand-off will play out among the rest of the population.

A short, informal survey around the capital Kiev, a city which speaks both Russian and Ukrainian, yielded (tentatively) some unpredictable results.

A number of native Russian speakers said that they were against giving Russian official status. They felt that ultimately Ukrainian should be the country's dominant mode of communication.

While Ukrainian speakers said that they did not oppose giving Russian a more elevated status.

"Ukrainian will win out in the end," said Svitlana, a native Ukrainian speaker who supported the new legislation.

Whether the law becomes a reality is still an open question, however.

In order for it to enter into force, it needs to be signed by the parliament speaker, who has tendered his resignation in protest over its passing, and President Yanukovych.

The Ukrainian leader said that he would reach a decision after he "studied all questions" relating to the legislation.

- Published4 July 2012

- Published5 June 2012

- Published27 January