Holocaust in France: Exhibition documents deportation

- Published

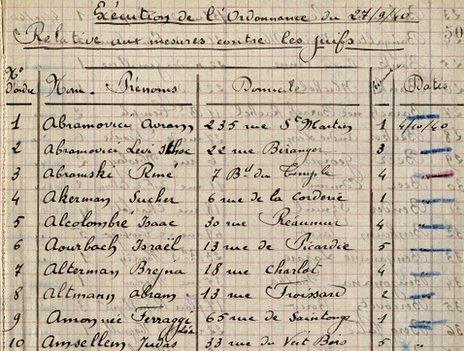

The documents include the Nazi-ordered 1940 census of Jews in Paris

The only surviving police archives of the biggest World War II deportation of French Jews are being opened up to public view for the first time.

One of the most extraordinary documents on show is Memo 173-42. It is dated 13 July 1942 and marked "secret".

"The occupying authorities," it reads, "have decided upon the arrest and grouping together of a certain number of foreign Jews."

Over nine pages, the head of the Paris police details his orders for the enactment of the Holocaust on French soil.

Three days later, a few hours before dawn on 16 July, French police operating in groups of two (one in uniform, one in plain clothes and accompanied by a German soldier), arrested more than 13,000 Parisian Jews.

"Many, many documents of this period were destroyed at the end of the war," says Olivier Accarie-Pierson, curator of an exhibition that has just opened at the town hall of Paris's third arrondissement, or district. "It's very rare. This is unique."

Mysteriously, in this district and in no other, the documents testifying to the daily life of Paris during the occupation escaped destruction.

Whether it was an act of civil disobedience or an administrative oversight, nobody knows why the records survived, Mr Accarie-Pierson says. But one day - about 20 years ago - they were discovered in a cupboard.

They are a treasure trove for historians.

Like animals

Although this is the first time they have been put on public view, historians have been studying them since they were put into the central Paris police archive, a mine of information about the minutiae of Parisian life stretching back to before the French Revolution.

President Hollande honoured the victims of the round-up on the 70th anniversary

Other documents on display are the lists of names - hundreds and hundreds of them - written in a ledger by meticulous French policemen during the census of Jews ordered by the Germans as soon as they occupied Paris in 1940.

That census was updated in 1943 when Jews were forbidden from listening to the radio and ordered to hand in their wireless sets.

The names and addresses of those who complied were taken down and used for future round-ups.

Poring over the documents in this exhibition, it is difficult not to be shocked by the clipped, official language employed.

"And yet we were talking about thousands of people!" says Mr Accarie-Pierson. Men, women and children who would soon perish in Nazi death camps.

The Jews were sent to two camps - the Winter cycling track (Velodrome d'hiver or Vel d'hiv) in the west of Paris and an internment camp set up just outside the capital at Drancy.

Although no photographic evidence has survived of their interiors, conditions must have been hellish.

"Where were the beds?" I ask in front of a post-war photo taken of the inside of the cycling stadium. " Around the edge there?"

"There weren't any beds," says Mr Accarie-Pierson.

In Paris, the Jews were already being treated like animals.

Acts of courage

Police chief Rene Bousquet collaborated directly with the Gestapo to facilitate the round-ups and the bureaucratic language sometimes lets through a glimmer of disdain for the Jews from other police chiefs.

After a few weeks all the Jews rounded up on 16 July had been deported by train, mostly to Auschwitz.

"The Winter cycling track has been liberated," writes one police officer.

"A few personal belongings and 50 sick people were left behind. Everything has now been transferred to Drancy."

Olivier Accarie-Pierson says: "The police obeyed the German orders but they also guessed what the Germans wanted and acted accordingly before the Germans asked them to."

The Germans, however, were angry that the French did not round up more Jews that week.

The French police expected to arrest slightly more than 27,000 people.

If they did not get that number, it is thanks to the moral courage of individual police officers.

"A few days before the arrests, many policemen went to the home of the people that they were supposed to arrest and said to them 'When we come on 16 of July, when we knock on the door, make sure you're not there, you have to escape!" Mr Accarie-Pierson explains.

Many were warned and fled but few thought they would arrest women and children too. This explains why, out of the 13,152 arrested that night, almost 10,000 were women or children.

Saved by neighbour

One of those police officers helped save the family of Moise Weinflasch.

He - like many others coming to this exhibition - was looking for a trace of his family. During the war, his parents and sister lived just down the road from here.

Some Parisians wore fake yellow stars to protest against the treatment of the city's Jews

"They escaped because they were informed that they would arrest Jews," Mr Weinflasch recounts.

An old woman who lived nearby hid the family when they asked her. "Five of them in a 60 sq m [645 sq ft] flat," says Mr Weinflasch.

He and his family are still in touch with the family of the woman who saved them, six generations later.

One other extraordinary sign of rebellion against what the Germans were doing you can see here in this show: the mock yellow stars that some young non-Jewish Parisians made and wore to mock and protest against the Nazis' racial policy.

There is one in the exhibition bearing the word Goi - the Hebrew word for gentile or non-Jew. There are others worn by jazz fans called the Zazous emblazoned with the word "swing".

Dozens of Parisians were interned for wearing these yellow stars of protest, as the exhibition shows - many in a former infantry barracks called the Tourelles in the east of Paris, many others in Drancy.

They were made to wear on their clothes the inscription "Amis des Juifs" (Friends of the Jews). They were imprisoned for two months before being released.

As for the 13,152 people they were accused of sympathising with, all but a tiny number were killed at Auschwitz.

The exhibition runs until early September.