Spanish miners in Leon hold out against austerity cuts

- Published

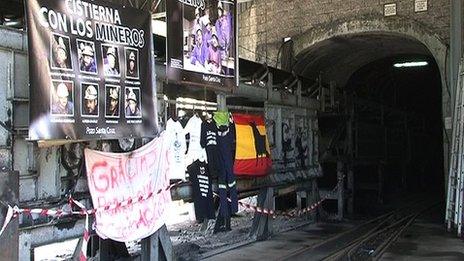

No light at the end of the tunnel? The strikers believe the government's subsidy cuts could finish off mining in this part of northern Spain

Near the entrance to the mine at Santa Cruz del Sil in Leon, a poster had been stuck to a window.

"Bankia," it read, referring to the troubled bank which is getting more than 20bn euros (£16bn) in aid from the Spanish state, "is the deepest pit of all."

For more than two months, this remote mining valley has been at the centre of a bitter strike that has put the miners at the forefront of resistance to the government's austerity programme.

Many mines are going back to work today, even though the government has not budged an inch in its plans to slash subsidies for the mining industry.

But Santa Cruz del Sil is holding out, perhaps for only a few days, until the workers receive more guarantees from the company that owns this mine.

Miners across Spain are starting to go back to work after a bitterly contested strike lasting more than two months

I travelled 500m (1,640ft) underground to meet a group of five miners who have been occupying the pit for the last three weeks. A previous group of men had stayed in the mine for more than seven weeks.

"We're here to defend everybody," said one of the miners, Eliseo Otero Robledo. "It's about our lifestyle and mining in this region, because we've got nothing else."

A doctor came down with us to check on the miners' health, but that seemed to be the least of their worries. It is the mining industry that is in critical condition.

The EU has said subsidies for mining should be phased out by 2018 anyway. But the Spanish government's austerity drive is speeding up the process dramatically, as well as cutting other social benefits to mining communities as well.

End of an era

The government insists that it can no longer afford to subsidise such an uncompetitive industry, and plans cuts of 63%. The miners say they have to take a stand.

"Because they've never invested in any other industry here," Eliseo argued, "this is all we can do. And mining can't survive without help."

Santa Cruz del Sil's miners are determined to face down the government

Another miner, Jose Antonio Paez Rodriguez, gave me a quick tour of the cramped quarters where the men have been living underground.

There was a table, a makeshift shower, food and newspapers brought down from the surface. There was a bird in a cage, and on the walls, messages from friends, family and supporters around the world.

They even got a postcard from the miners who were famously trapped underground in Chile.

"And this," Jose Antonio said, gesturing grandly to a corner of the room, "is the main dormitory".

Five small beds were crammed together. On the wall above them, someone had pasted a cardboard cut-out of the sun.

"I really miss the daylight," Jose Antonio said. "When I get out of here I want to see two kinds of light - the sun in the sky, but also my future."

Spirits down the mine are good, but it still feels like the end of an era is approaching. There are only about 5,000 coal miners in Spain now - a quarter of a century ago it was nearly ten times that.

So is further decline inevitable? Eliseo Otero Robledo acknowledged some parallels with the miners' strike in Britain in the 1980s.

"It was sad what happened there," he said, "and it's possible they will do the same to us, but we hope not. We will do everything we can to continue the fight."

And the miners have captured a growing mood of defiance to government cuts in Spain. In many ways, mining is a hugely privileged sector of the economy, but when a "long march" by miners from Asturias and Leon reached Madrid last month, thousands of people turned out to meet them and show their support.

Back at the pithead in Santa Cruz del Sil, family members have been arriving every day with food and other supplies to be taken down the mine.

"The government can find money for the bankers," said Eliseo's wife, Noelia, as she sat on a bench in the sun. "It can find money to build motorways, but for us here? Well, it seems to me that there's a lack of political will."

There have been increasingly bitter clashes as the strike has progressed. Miners have blocked roads and railways and fought some pitched battles with the police. Tear gas and rubber bullets versus homemade rockets and slingshots.

Regional identity

"There's a feeling in some mining areas," said Rudolfo Gutierrez, a sociology professor at the University of Oviedo, "that if this is their final battle, if the industry's going to die, then they'd rather die standing up".

Miners' wives held a sit-down protest in Gijon

"Mining is part of the culture; the history is so strong that it's part of the regional identity in places like Asturias and Leon."

It is a history of struggle - of working class militancy and the fight against fascism during the Spanish Civil War. Now, the miners are part of a battle to determine the future of the Spanish economy.

But this time, history may not be on their side.

"During the last 20 years an average of 1bn euro a year has been given in economic aid to the mining areas," Prof Gutierrez explained. "It's very difficult to maintain that kind of support for such a small number of miners."

For now the strike is pretty much over, apart from a few hold-outs like Santa Cruz del Sil. Most miners are returning to work because they need the money.

But it is conflict delayed, not conflict resolved.

Miners' wives were demonstrating on the streets of Gijon this week, a city on the Asturian coast. They staged a brief sit-in blocking city centre traffic, and sang traditional mining songs.

"Whatever happens our protests will continue," Maribel told me. "What other choice do we have?"

So far, the government has given no ground, and it has little room for manoeuvre.

But further unrest looks likely as the squeeze on Spain's economy - the painful adjustment the government says it needs - really begins to bite.