Georgia election: Battle for the country's heart

- Published

Many of Bidzina Ivanishvili's supporters are attracted by his 'good guy' image

Georgia has just announced that parliamentary elections will be held on 1 October. They are being seen as the biggest test facing the country's democracy since the Rose Revolution in 2003.

Until the end of last year it looked like President Mikheil Saakashvili's governing party would win this election easily. A boringly predictable affair - welcome in a country where elections can provoke crisis and instability.

But now the volatility is back in Georgian politics.

The country's richest man, Billionaire tycoon Bidzina Ivanishvili, whose $6.4bn (£4.1bn) fortune is worth almost half Georgia's economic output, has vowed to oust the ruling party from power. And the fight is getting nasty.

'Facade of justice'

Mr Ivanishvili accuses the government of targeting him, in an attempt to stamp out political opposition.

He says he has been fined more than $200m, allegedly for breaking party funding rules. After moving to the opposition, he was stripped of his Georgian nationality, ostensibly for holding other citizenships, he says. And his supporters claim they are being harassed by the authorities.

According to Mr Ivanishvili, it is all part of President Saakashvili's strategy to crush any political opponent.

"He has managed to persuade the US and Europe that he's building a real democracy. But nothing like that has been happening in this country over the last few years.

"The biggest injustice which we have in Georgia right now is this facade of pretend justice," Mr Ivanishvili said.

But the government alleges that Mr Ivanishvili is illegally using his massive wealth to skew the political landscape.

He is accused of breaking strict laws on how political parties should be funded. These cap the amount individuals and companies can donate.

Mr Ivanishvili is suspected of transferring funds via third parties to get round the law, or of receiving illegal corporate donations in the form of free office space or transport for political activists.

And his charitable donations, of around $100m a year, are nothing more than voter bribery, says governing party MP Davit Darchiashvili.

"Personalities in politics and personal allegiances mean more than political programmes here," he says. "So when someone comes and says that I'm going to pay whoever supports me, it's a risky thing for Georgia's development towards democracy."

Philanthropy

Georgia's richest man, Bidzina Ivanishvili, says the president is trying to crush dissent

There is not much difference in concrete policy between the two sides.

Both have announced ambitious plans to tackle the country's high levels of poverty - mainly by throwing money at the problem.

But the battle for power has created a fault line down the middle of Georgian society.

With a reputation for benevolence and philanthropy, Mr Ivanishvili is popular among many poorer voters who are struggling in modern Georgia's neo-liberal economy.

He funded public buildings in Tbilisi, including the cathedral and the university. And even paid MPs' salaries and bought uniforms for the police in the first years after the 2003 Rose Revolution.

Talking recently to market traders who scrape by earning a few dollars a day, an enthusiastic thumbs-up was given every time Mr Ivanishvili was mentioned - although it was difficult to find concrete reasons why they liked him.

"He's a good guy," was the usual answer. At the market, it was difficult to come across anyone who supported the government.

Mr Ivanishvili is also backed by many older Georgians, who feel left behind by President Saakashvili's young, savvy elite.

And urban intellectuals accuse the president of authoritarianism, saying he controls the courts and the mainstream media.

They feel this fervently pro-Western government has undermined Georgia's artistic and intellectual traditions, in favour of a more superficial American-style society.

But for many other Georgians, with memories still fresh of the war-torn and crime-ridden 1990s, President Saakashvili's team has brought an unprecedented period of stability and economic growth.

And his government is open and tolerant towards religious, sexual and ethnic diversity - compared to which some of Mr Ivanishvili's colleagues are worryingly nationalistic.

Frequent fistfights

When he came to power after the 2003 Rose Revolution, President Saakashvili swept aside the corrupt Soviet-era elite.

He fulfilled many of the promises he made to the cheering crowds from the steps of parliament - he was tough on criminals, made the streets safe and got the lights working again.

Many voters are afraid that without Mr Saakashvili's ruling party, the country could slip back into chaos.

One of them is Nino, an elderly woman who supplements her pension by selling small pots of honey and home-made wine from a tiny cave of a shop.

Like many people, she fears returning to a time when Georgia was a failed state.

And she's suspicious of the leader of the opposition, who earned his wealth in 1990s Russia, and is accused of having links with the Kremlin.

"I don't think [Mr Ivanishvili] has the brains and experience needed to run the country - he'd have to rely on having clever people around him. But they would just act in their own interests. So the country would be torn apart."

As October's elections approach, tensions are mounting - fistfights between supporters of both sides are frequent.

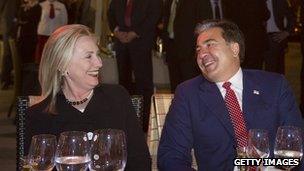

President Saakashvili is considered reliable, but many say he has fostered a superficial society

At one recent campaign meeting, at least a dozen activists and journalists were hospitalized after a fight broke out. Western observers hope the elections themselves will pass off more peacefully.

But a lot is at stake. President Saakashvili's ruling party has a lead in all independently-funded and well-respected polls.

But Mr Ivanishvili has already said that he does not accept these figures, and has refused to sign a pledge to accept the outcome of the election peacefully.

This has led to fears that the opposition may dispute the results and provoke unrest.

But this vote is also the biggest challenge yet to face President Saakashvili's party.

In the West the elections are being seen as a litmus test to show how far along Georgia is on the path to eventual Nato and EU membership, and whether the government can live up to its promises of democratic reform.

When there was no opposition it was easy to espouse democratic values of free and fair competition.

But faced with a wealthy opponent who is supported by a large chunk of the population, those democratic ideals are now being put to the test.

- Published3 October 2012

- Published31 December 2024