Paris Notre Dame cathedral turns 850 years old

- Published

She stands in effortless command of the small island where medieval Paris was re-founded. Centuries of history have flowed past Notre Dame with the grey waters of the River Seine.

The mighty cathedral is neither the tallest, oldest nor biggest in the world, but it can rightly claim to be the best-known.

For centuries it has witnessed the greatest events in French history: 80 kings, two emperors, five republics - and two world wars.

Its famous gargoyles, there to guard against the evil spirits, have faced both glory and tragedy over the centuries.

The cathedral, with its original 13th-Century rose window, was pillaged and nearly demolished in revolutionary France.

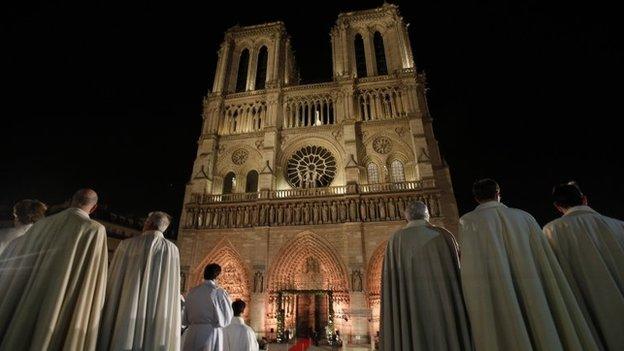

The great Paris cathedral has seen crusaders and kings praying before battle

She survived, and this month sees the start of a year of special events celebrating the landmark 850th anniversary of "Our Lady of Paris".

Holy wars

The first stone was laid in 1163. It took them 180 years to complete it. Yet as the magnificent structure took form, history was already playing out in its shadows. Crusaders prayed beneath the world's first flying buttresses as they set off on holy wars.

Within the walls, in 1431, a sickly boy of ten, King Henry VI of England, was crowned King of France.

And in 1804, to the sound of the 8,000 pipes of the cathedral's Grand Organ, Napoleon was crowned emperor.

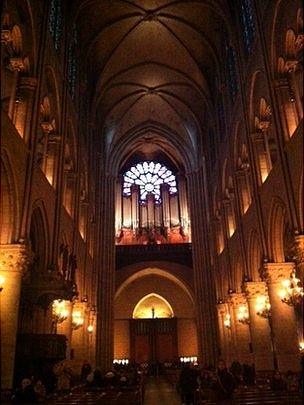

Music is integral to the life of the cathedral; in the archive, the medieval manuscripts reveal it always has been.

Fittingly, then, the great sounds of Notre Dame will be at the heart of the anniversary celebrations.

Throughout next year, three choirs will bring to life some of the earliest sounds of Christianity.

Choir director Sylvain Dieudonne told me that, "in 1163, when they started building the cathedral, Paris became a centre of great intellectual, spiritual and musical development.

Quasimodo's bells

"The musical school was hugely influential," he said. "We know from the manuscripts we have recovered that it influenced music across Europe - in Spain, Italy, Germany and in England."

Why Notre Dame is getting new bells

But there is another sound for which the cathedral is well known. The bells and "the grand peal" that so enthralled the hunchback, Quasimodo.

The biggest of them all is Emmanuel, installed in the south tower in 1685. It tolls to mark the hours of the day, as it tolled to mark the liberation of the city in 1944.

But this year, the smaller bells from the north tower are being recast; they are not the originals. Those were melted for cannon balls by the revolutionaries.

Their 19th-Century replacements were "discordant".

Eight of the bells are being made in Villedieu-Les-Poeles, in Normandy, using ancient Egyptian methods; the moulds are fashioned from horsehair and manure.

"It gives the bell a perfect skin, far better than if you made it with sand and cement," said Paul Bergamo, the foundry president.

'Best bells in France'

"But we are also using a lot of computerised techniques to hone the sound of the bell.

"We will use a spectral analyser to check the final tone. They will all be tuned to the great bourdon bell Emmanuel. It's really a mixture of the best technology - and the best of traditions. And I am confident that when we have finished this will be the best set of bells in France"

Music has been part of Notre Dame's history since medieval times

The year-long festival would not be complete without a celebration of the architecture. And to mark 850 years they will be improving the lighting.

The building was not originally designed to include the flying buttresses around the choir and nave, but after the construction began, the thinner walls grew ever higher and stress fractures began to appear as the walls pushed outward.

In response, the cathedral's architects built supports around the outside walls, and later additions continued the pattern.

Today the cathedral stands as a gothic masterpiece.

In his book The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Victor Hugo encapsulated that power.

"When a man understands the art of seeing," he wrote, "he can trace the spirit of an age, and the features of a king, even in the knocker on a door."

- Published22 February 2012

- Published9 December 2012