Exploring the corridors of the Hague tribunal

- Published

A BBC exclusive behind the scenes access to the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia).

For nearly two decades, an unassuming building in The Hague has been quietly creating history.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was the first war crimes tribunal created since Nuremberg at the end of World War II. It has indicted 161 individuals, including senior politicians and military leaders.

The BBC has been allowed unprecedented access to the inner workings of the tribunal.

In the bowels of the building sits a heavy, six-lever metal door, probably bomb-proof. It harks back to the time when the place was owned by an insurance firm.

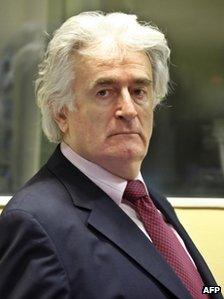

Radovan Karadzic is defending himself

The door used to be the entrance to the company's vault, where its most important documents and files were kept. Today the door is unnecessary but the vault has been turned into a series of Spartan holding cells, a place for the accused at the court to sit and meet their lawyers before going upstairs to the courts.

Each cell has a small, simple table and two plastic chairs and every defendant has had access to the same basic facility.

All except Slobodan Milosevic. Such was the media interest in the trial of the former Yugoslav leader that Paddy Gavin, the Irish carpenter in charge of the cells, was forced to create a small bedsit for the ex-president so he could arrive very early, ahead of the media.

"We fitted it with a bed and a wardrobe and somewhere to write and a lamp," he recalls. "All the furniture had to be screwed together and fixed to the floors and the walls."

Interns

A couple of floors above the vault sit the courts themselves. The highest-profile current defendant is Radovan Karadzic, former leader of the Bosnian Serbs.

He is accused of genocide and crimes against humanity, including at Srebrenica, where more than 7,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys were murdered.

But despite the seriousness of the charges, he has chosen to defend himself, an idea he got from watching Milosevic employ the same tactic during his trial.

Mr Karadzic does get legal help however, and in a small cramped office sit eight young, eager, fresh-faced interns.

Law students drawn from around the world, they are excited to be working on such a high-profile case.

One of the interns, 24-year-old Zygimantas Juska from Lithuania, says: "He knows a lot from his life and experience so he can provide a lot of valuable information to someone young like me. He's done a lot in his life."

Corralling that enthusiasm is Peter Robinson, a defence lawyer from San Francisco who is one of Mr Karadzic's legal representatives.

He similarly describes the Bosnian Serb positively, talking of a "funny, personable, humble, grateful" man, but he acknowledges it is unlikely his client will ever be freed.

"He may know in his heart [that he'll never be freed] but he's a real optimist... and I think he has some hope, maybe unrealistic, that some day he could be," he said.

Ranged against that hope are millions of pages of documents held behind the locked doors of the court's evidence vault.

Grim work

Thousands of people were held in Omarska camp

Stacked in neat brown cardboard boxes, they contain the horrors of the wars in the former Yugoslavia - the evidence of witnesses, the forensic material gathered on the ground, the transcripts of incendiary interviews given at the time.

Bob Reid, a plain-speaking former Australian police officer who has worked here for nearly two decades, recalls carrying out much of the tribunal's early, grim investigative work.

He said it was "chilling" to walk into the notorious Serbian detention camp, Omarska, with its torture chamber known as the White House, "where we knew terrible crimes had occurred".

"The political elite, the police officers, the clergy - had all been put in there and none of them came out. And [we] were still finding traces of blood."

It is little wonder he took particular delight in securing the capture of Mr Karadzic and his erstwhile military leader, Ratko Mladic. "They were nice days, they were good days. There was one beer or two had in Belgrade."

'Testimony fatigue'

While a lot of the evidence against Mr Karadzic and Mr Mladic, whose trial is also under way, is on paper, it is the evidence of witnesses that make the trials come alive.

Several witnesses, from either the defence or the prosecution side, can pass through the court each day.

The tribunal has a particular section, the Witness Support Unit, that takes care of people who travel to the court.

Some have been called to testify on several occasions, giving evidence in more than one trial, not just at The Hague but in courts in the former Yugoslavia.

The whole experience can put severe pressure on the witnesses, says Helena Vranov Schoorl from the unit:

"It's like they are stuck in the past.

"They call it a bit of a testimony fatigue. As one of the witnesses said - once a witness, always a witness. The witnesses feel exhausted, especially if you are forced to live in the past."

The call of The Hague on those witnesses is reducing.

The last trials are under way, with verdicts expected by the end of 2014, although appeals could mean the court continuing to operate for a couple of years after that.

Despite the dozens of defendants and thousands of witnesses who have passed through this ground-breaking tribunal, many staff here remain befuddled as to what caused former neighbours to turn so viciously, so violently, on each other.

They may never know - so they will simply continue to work towards trying to ensure that such brutality is never repeated.

- Published28 June 2012

- Published12 July 2012